This article first appeared in The Edge Financial Daily, on September 25, 2015.

IN my trip through the central Athens polling stations on Sunday, I met only one voter who seemed cheerful. Alkaios Klaoudatos is a supporter of Syriza, the leftist government that has held power since January, and he was confident that his party was going to win the election.

In fairness, virtually everyone I’ve talked to since the Friday polls were released has said Syriza was going to win a plurality. But Klaoudatos, a lawyer, believed his party was going to take enough votes to form a government with its previous coalition partner Independent Greeks, or Anel, rather than seeking to share power with a larger partner such as Pasok, the old left-wing party that was pushed aside by Syriza.

At 4pm on Sunday afternoon, that seemed a little crazy. Anel is a small right-wing party that none of the other parties is keen to form a coalition with. In order to make it work, Syriza would need a more sizeable majority than the polls seemed to project.

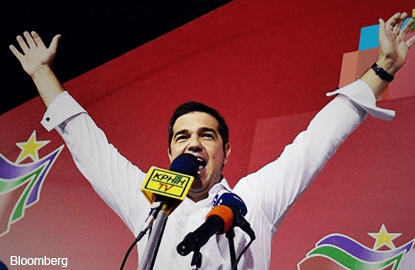

By Sunday evening, as the results poured in, it started to look prescient. By 8.40pm local time, Vangelis Meimarakis, the head of the centre-right New Democracy party had conceded, and Alexis Tsipras, the head of Syriza, had announced his intention of forming a government that night.

The results, in fact, look strikingly similar to the election that brought Syriza to power, on the back of promises to take a harder line against the country’s creditors and their stringent demands for austerity and reform. Golden Dawn, the far-right anti-immigration party, picked up a seat or two, led by gains in the islands that have been hardest hit by the refugee crisis.

The Syriza-Anel coalition had their vote percentage shaved a bit. Nonetheless, it’s pretty close, especially considering that in the intervening months, Alexis Tsipras led Greece into a showdown with Greece’s creditors — a showdown that ended not with a rousing victory for the radical left against the heartless forces of capitalism, but with capitulation to the creditor’s demands, a banking crisis that is still pinching Greeks with capital controls, and a bailout deal that is worse than the one on offer before Syriza started playing hardball.

Not out to punish Tsipras

But, apparently, Greek voters didn’t want to punish him for it — or at least, not the ones who bothered to turn out to vote. “They are new, they are clean” said Maritza Pantelakis, a French-Greek citizen who lives in France, but had come to Athens to vote for Syriza. “They made errors, but they fight.”

“We may not have won the battle, but we will win the war,” Klaoudatos told me.

In fact, Tsipras seems to be in a somewhat better position than he was before he called this election, even though his percentage of the vote looks as if it fell slightly. With the left-wing hardliners gone from the party, Tsipras will probably find it easier to tackle the difficult task of implementing the agreement.

In less than a year, Greece has gone from electing an anti-bailout firebrand to re-electing a pro-bailout incumbent. “It makes no sense, does it?” Stavros Messinis, a local entrepreneur said.

“Welcome to Greece,” said my translator.

That said, this isn’t exactly a resounding endorsement for Syriza. The general sentiment among all the voters I spoke to — Klaoudatos excepted — was that they were not so much choosing a government as choosing the folks who would implement decisions made outside of Greece. And that wasn’t exactly a thought that inspires fierce passion.

“We are only management,” I was told by a Golden Dawn supporter in central Athens. “It is the people who gave us money who will decide what happens.” A supporter of Potami, the technocratic centrist party, said he was finally hopeful that things would get better after the election — not because he liked Syriza, but because the latest bailout agreement is so strong that “it can’t be avoided”.

Tough choices ahead

That doesn’t mean, however, that it will be easy, or that the outcome is certain. The failure of previous governments to put reforms in place or get the country back on the path to growth demonstrates just how difficult it is.

Greece is out of money, and dependent on creditors who want to see strong measures that will offend politically sensitive groups. Syriza is ideologically opposed to structural reforms that involve firing public employees, which means relying more heavily on tax increases that may stunt recovery.

And the last few months do not exactly inspire wild confidence in Tsipras’ political management skills. His campaigning is obviously very good. But campaigning is not at all the same thing as governing effectively.

Greece has an opportunity right now to push through tough reforms, get some debt relief, recapitalise the banking system, and start the country back toward growth. But a memorandum of understanding with the creditors is not going to do the job by itself.

Parliament will have to pass difficult bills that will mean pain for large numbers of people, and then ensure that the ministries carry out that legislation effectively. They’ll be facing even tougher opponents than their troika of creditors (the European Commission, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund): a well-entrenched clientelist system, and Greek voters angry about having pain piled upon pain.

As he stood before his supporters to celebrate his victory on Sunday, Tsipras pledged to continue the fight that they started seven months ago. He is certainly going to have a fight on his hands. Tsipras negotiated the agreement, and now will have to implement it. The question is whether he has that much fight left in him. — Bloomberg View

Megan McArdle is a Bloomberg View columnist.