This article first appeared in Personal Wealth, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 16, 2020 - March 22, 2020

Population ageing is expected to raise the debt and financing requirements of many advanced economies in the coming decades, according to a report by Moody’s Investors Service released on March 4. In addition, a shrinking labour force and lower private domestic savings due to a growing ageing population will constrain funding for governments in those economies.

The report notes that the twin pressures of shrinking labour force and lower private domestic savings will leave politically challenging fiscal consolidation, higher interest rates and central banks holding more considerable government debt as potential adjustments. Increased borrowing needs amid lower household saving flows mean new or additional financing gaps for countries with ageing populations.

“In the near to medium term, household saving rates may rise in anticipation of more time in retirement. However, empirical evidence suggests that over the longer term, population ageing is likely to lower household saving rates as the proportion of retirees to the working age population increases,” says the report.

According to the report, advanced economies will witness a negative savings flow (decline in stock of savings) because workers tend to save for retirement during their active working years, then use the accumulated savings to supplement their disposable incomes once they reach retirement age.

This implies that even if saving rates are stable across age groups, a falling share of productive workforce and a rising share of the retirement population will lower average household saving rates across the nation over time.

Unlike previous generations, citizens are preparing to spend a longer time in retirement due to an increasing life expectancy as a result of better healthcare and medical research, which adds to the domestic expenditure, says the report.

Moody’s conducted an analysis to estimate the long-term relationship between household saving flows and ageing populations. It determined that households would likely begin to or rapidly draw down on their pool of savings by 2040. The analysis covered Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, South Korea, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain and Switzerland — countries that have the fastest ageing populations globally.

The analysis notes that household saving rates have already declined in a number of ageing economies, in particular Greece, Italy, Japan and Poland. The exceptions are Switzerland and Germany, where saving rates are currently significantly higher than in the other 10 countries, or 11% and 6% of GDP in 2018 respectively.

Moody’s has also run simulations to look at the implications of lower private domestic savings on government financing, by comparing the household saving trends from the previous analysis together with government fiscal balances to derive estimates of government financing gaps. The simulations suggest that government fiscal balances will deteriorate significantly by 2040, with all but Germany potentially recording a fiscal deficit. It found that half of the economies analysed would face new and wider financing gaps in the absence of policy measures that offset the budgetary impact of ageing.

While the simulations suggest that the other six advanced economy sovereigns will continue to have sufficient net private savings to fund government deficits even in 2040, the financing surplus of these governments would shrink substantially, says the report. “In our simulations, Greece and Italy face the largest financing gaps of around 15% of GDP by 2040. Financing gaps in Japan and Portugal would also be sizeable, exceeding 5% of GDP by 2040, and modest financing gaps would open in Austria and Spain. In terms of public debt burdens, our simulations suggest that government debt for both Italy and Japan could rise to around 100 percentage points or more of GDP by 2040 in the absence of policy adjustment. In Greece and Spain, debt would rise by 20 to 40 percentage points of GDP during the 2030s, although after a decade of declines.”

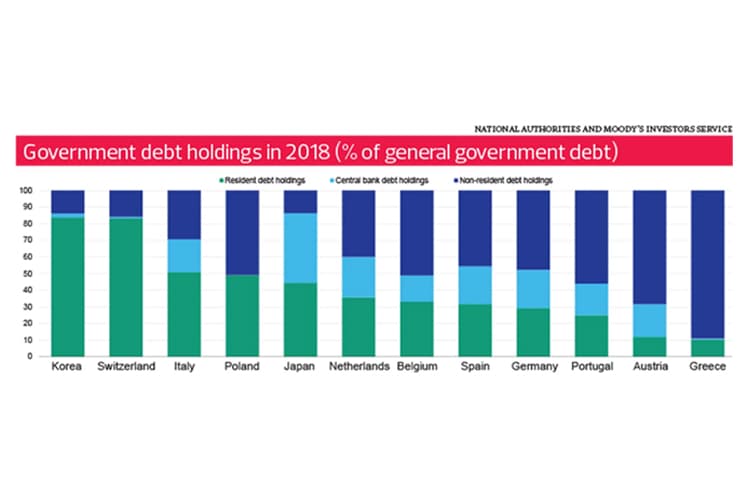

Historically, private domestic savings have been an important source of government funding, says the report. In Italy, Japan, South Korea, Poland and Switzerland, private domestic savings, including investments through banks and other financial intermediaries, funds more than 40% of general government debt.

Hence, policymakers in fast-ageing advanced economies are likely to employ a combination of policy tools in adjusting to lower private domestic savings, it adds. Governments may choose to cut spending and raise revenue to limit their borrowings to offset the impact of ageing on fiscal balances.

Fiscal challenges from a growing ageing population

However, the report says the combination of increased financing needs and lower private domestic savings may lead to a country’s greater reliance on other sources of financing, namely foreign investors and their respective central banks.

According to the report, a higher reliance on foreign savings is likely to raise the cost of access, particularly when emerging economies — which have higher borrowing costs than advanced economies — account for a larger share of global savings. Currently, the average borrowing costs and interest rates in many of the fastest-ageing advanced economies are very low relative to the past two decades, even when compared with other developed economies that typically have low-risk premiums, such as the UK (AA2 negative) and the US (AAA stable).

This reflects the persistently weak growth and low inflation over the past 10 to 12 years that have resulted in policy interest rates at or close to zero, says the report. As a result, governments will be able to refinance debt in the next few years at lower costs than 7 to 10 years ago.

However, if governments increasingly rely on foreign savings to plug their financing gaps, overseas investors may demand higher risk premiums, particularly from governments whose capacity to attract stable external financing is untested, says the report. The exception would be countries with reserve currency, such as the US dollar, that have a track record of stable overseas demand for their government debt, which is likely to continue attracting savings even with relatively low interest rates.

The report says emerging economies will gradually account for a larger share of global savings. That is because growth and inflation will remain faster in most emerging economies than in advanced economies, and savers are likely to demand higher real and nominal returns on their savings.

This may further raise borrowing costs for the fastest-ageing advanced economies and weigh on debt affordability and government liquidity, says the report. Should financing costs rise over a sustained period, for some of these economies, debt affordability will weaken while liquidity risk will increase from its current low levels.

“We expect policy rates and borrowing costs more broadly to remain low over the next several years because of structural forces weighing on spending — even if cyclical headwinds eventually dissipate and lift interest rates from historically low levels. However, a declining supply of private savings, combined with structural changes to the source of global savings, at a time when demand and competition for savings are likely to rise, will push borrowing costs higher over the long term in the absence of intervention by monetary authorities,” says the report.

According to the report, obtaining debt with higher interest rates from emerging economies may not be consistent with the conditions and goals set out by the local monetary authorities at different points of the economic cycle. Hence, central banks may ultimately increase their holdings of government debt over successive economic cycles.

However, for many of the countries discussed in the report, central banks already own a significant share of government debt. At about 40% of its portfolio, Japan’s central bank had the largest holdings of governmental debt in 2018 among the countries analysed, followed by the UK at about 25%.

“We do not expect central bank holdings will consistently rise because of ageing. Economic cycles mean that central banks may attempt to exit government bond purchases or monetary financing programmes, or even try to reduce their holdings of government debt and the size of their balance sheets consistent with their monetary policy objectives. However, over consecutive cycles, population ageing may inexorably result in higher central bank holdings of government debt, in part because of the challenge of fully unwinding purchases that occurred during an easing cycle,” says the report.

It cites the example of the US Federal Reserve halting its balance sheet reduction programme, which would have reduced its holdings of US Treasury bonds, that shows cyclical central bank purchases of government debt can be difficult to unwind and can have structural implications for monetary authority holdings of such debt.

Another example would be the European Central Bank resuming its government bond-buying programme, even before eurozone central banks had the chance to start reducing their stock of government debt holdings. According to the report, a more extensive holding in government debt could lead to several challenges in monetary policymaking from the central bank’s perspective.

Calibrating monetary policy in an environment where interest rates, growth and inflation remain relatively low, even at the peak of the economic cycle, prevents a substantial unwinding of government bond purchases, which challenge monetary policy effectiveness, says the report.

Higher central bank holdings of government debt may also disrupt bond market pricing by reducing the proportion of government debt held by private market participants, thus lowering market liquidity. A bond market with reduced liquidity and depth will increase market volatility, which may spill over into the broader credit and financial markets and further undermine monetary policy transmission, says the report.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.