This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on June 7, 2021 - June 13, 2021

EVER since the first blanket automatic loan moratorium ended in September 2020, it has been a topic discussed at various levels of society, from the general population to the highest levels of policymaking circles.

I want to share my thoughts on this matter, including whether we can pursue another round of blanket automatic loan moratorium. However, the emphasis should be more on whether we should, and the case for targeted repayment assistance.

Different context, different approach

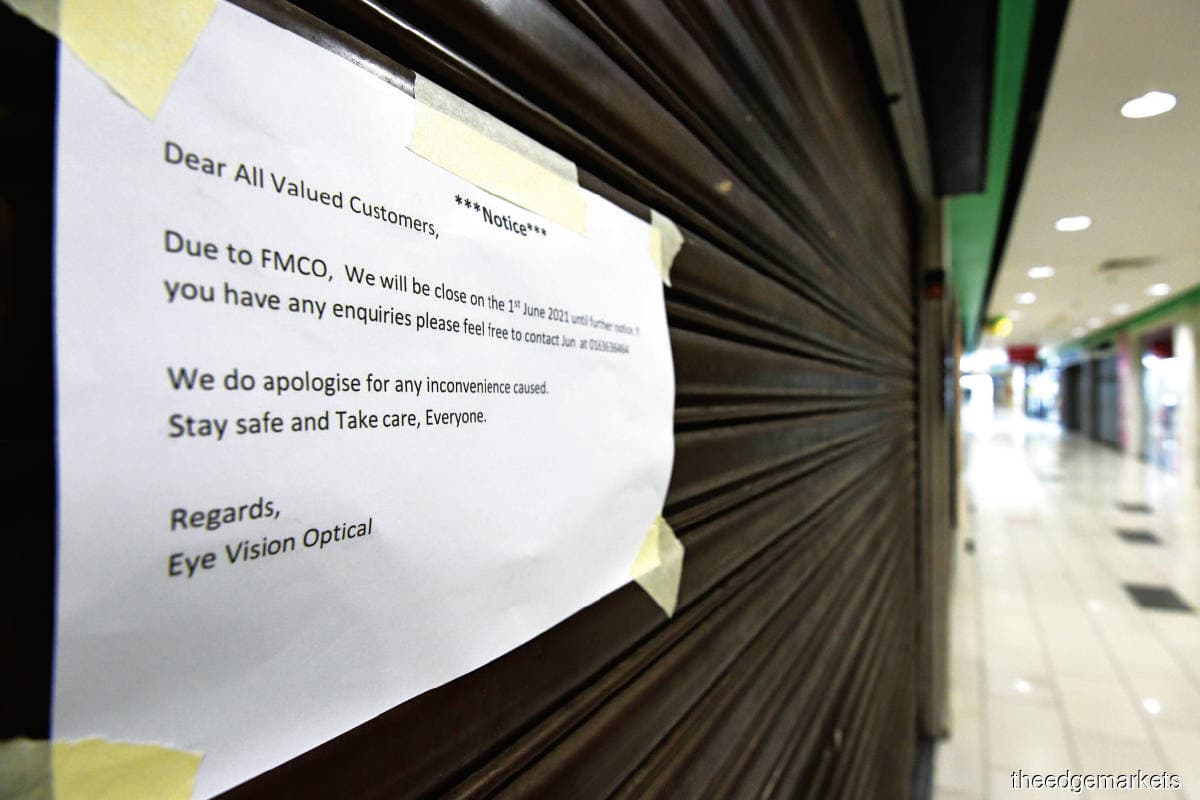

When the blanket automatic loan moratorium was implemented last year, the situation was unprecedented. The Covid-19 virus was new to all of us — how it transmits within the community or how it impacts the economy as a whole. From MCO 1.0, we announced broad-based and strict containment measures, permitting just a handful of essential sectors/services to operate. Inevitably, it affected people from all walks of life — the poor, rich, urban, rural and formally or informally employed.

Equally broad-based was our response to lockdown measures via the Prihatin economic stimulus package announced in mid-March 2020, including a deferment of performing loan repayments for a period of six months. Then, there was no vaccine or exit plan in sight. Discussions around a viable vaccine for Covid-19 appeared only in April 2020, with a detailed report on the first human trial made available at end-May. Discussions regarding an exit strategy started around the same time when the government introduced the 6R Economic Recovery Strategy.

When MCO 1.0 was implemented in March 2020, Malaysia was the only country in Southeast Asia that implemented a blanket automatic loan repayment moratorium for individuals and small and medium enterprises (SMEs). According to Moody’s Investors Service, Malaysia implemented the most extensive loan moratorium in the region, covering about 80% of total loans. Ultimately, the blanket automatic loan moratorium implemented between April and September 2020 (estimated to be worth more than RM90 billion) was a proportionate response as all Malaysians struggled — an unprecedented measure in the face of an unprecedented crisis. In summary, broad-based containment measures led to broad-based assistance, including a blanket loan moratorium.

As we progressed through the pandemic, we now have better information and knowledge on the virus. This is complemented with data and information from the Laksana agency, which was established to monitor and ensure the effective execution of our assistance and economic stimulus packages. This has enabled us to be more targeted and focused in terms of which groups of individuals or businesses needed assistance.

So far, we have channelled over RM200 billion in assistance, benefiting 20 million Malaysians and 2.4 million businesses. As a result, we have seen signs of recovery in all economic sectors. In March 2021, GDP grew by 6% — the highest since Covid-19 hit our shores. To further reinforce this growth trajectory, we have set in motion our national vaccination plan, which has now accelerated (reaching 100,000 doses per day) towards our aim of achieving herd immunity by year-end. We have also refined our containment strategy, where the approach has been more targeted and localised.

Concurrently, this has led to more targeted assistance, including loan repayment assistance, which is extended to those most affected by the pandemic. Until year-end, in addition to the recently announced Pemerkasa+ stimulus package worth RM40 billion, more than RM100 billion in programmes and assistance are available and ongoing to further protect the people, support businesses and spur the economy, complemented by Budget 2021 initiatives worth RM322.5 billion. In summary, targeted containment measures led to targeted assistance, including targeted repayment assistance.

For each distinct context, we applied a distinct and proportionate approach to containment and assistance, including loan repayment assistance. What has not changed is our commitment to help Malaysians.

A moral consideration

There is a moral argument against the case for another round of blanket automatic loan moratorium: Why should a person whose income has not been affected by this pandemic enjoy a loan moratorium again? Who stands to benefit most from this?

A loan moratorium granted on a RM150,000 mortgage (assuming a 35-year loan at an effective interest rate of 3.3% a year) by a family would entail an instalment deferment value of RM3,612 over a six-month period. How much would a T20 family with a RM2 million mortgage benefit under the same arrangement? RM48,000.

When the first moratorium was granted, we saw an increase in bank deposits and retail participation in the stock market, suggesting that the people who could afford it were unnecessarily given the moratorium. Another key point of reference is the finding by Bank Negara Malaysia that, after the moratorium ended in September 2020, 85% of borrowers resumed repayments. This indicates that most Malaysians are in a position to continue repaying their obligations. Therefore, a strategically better option is to focus on the other 15% of borrowers who are struggling.

Ultimately, who stands to benefit most from a second round of blanket automatic loan moratorium, if not the well-off? This would be akin to prescribing medication that will disproportionately help those who are healthy and have recovered. Just because it is equal, does not mean it is fair.

The rakyat as indirect shareholders of the banks

As commercial entities, banks are responsible for providing returns to their shareholders. And who are the shareholders of these banks? They are the likes of Permodalan Nasional Bhd (PNB), which manages the Amanah Saham Bumiputera (ASB) unit trust fund; Kumpulan Wang Persaraan (Diperbadankan) (KWAP); Khazanah Nasional Bhd; Lembaga Tabung Haji (LTH); as well as pension funds such as the Employees Provident Fund (EPF) and Lembaga Tabung Angkatan Tentera (LTAT).

These entities, in turn, are indirectly owned by Malaysians via their savings invested through these entities. For example, for 2020, EPF received about RM298 million in dividends from RHB group while PNB, via ASB, received close to RM1.3 billion in dividends from Maybank group. Should the profits of these banks be affected, owing to a blanket automatic loan moratorium, the returns or dividend payments by these institutions and other shareholders will be pressured downwards. This will have wider implications for the rakyat, particularly in building their pension or emergency savings.

Systemic importance of the financial system

Beyond dollars and cents is the risk of another round of blanket automatic loan moratorium for depositors and on the stability of the financial system as a whole. The risk may cascade down to the real economy, including widespread withdrawal of funds, higher interest rates (higher cost of financing) and loss of investor confidence.

From an accounting perspective, loans that have been extended or repayments delayed are not classified as non-performing loans (NPLs) and could lead to heightened credit risk, should borrowers be unable to fulfil their repayment obligations. This risk is being carried by the banks. Loans turning non-performing could weaken the ability of the banking system to weather external shocks.

Despite Bank Negara’s loosening of the statutory reserve requirement in 2020 to 2%, which injected about RM30 billion of liquidity into the banking system, this weakening could entail an increase in the cost of financing, a reduction in liquidity or induce a bank run by depositors. Domestically, a pullback in credit is the last thing the economy needs now, when we are pulling all the stops to support national recovery.

Consequently, the capacity of banks to give out new loans to those who need them most will be affected. Moreover, if emergency and reserve powers are used indiscriminately to undermine existing contractual rights, there could be serious ramifications to business confidence, resulting in potential capital outflows and a weakening of the economy. Given the potential domino effect, in the worst-case scenario, we could be faced with a self-induced financial crisis on top of a health, social and economic one.

Bottom line: Targeted approach to repayment assistance

The bottom line is that repayment assistance is ongoing, available and forthcoming to those who need it most. Targeted repayment assistance is available to those most affected and vulnerable, including those who have lost their jobs — whether one is in the B40, M40 or T20 group. B40s have received Bantuan Prihatin Rakyat (BPR) while microenterprises as well as SMEs that have not been allowed to operate in this recent lockdown have access to facilities of up to RM150,000. These are the most vulnerable and most affected, and I cannot stress enough that they will be given assistance.

At their request for either a three-month loan moratorium or a 50% instalment reduction for six months, approval will be automatic. As for those who have experienced a loss in income, a proportional reduction in instalment amount will be automatically given, should they ask for it.

Targeted repayment assistance has proved to be effective. According to the Association of Banks in Malaysia, as at March 26, 2021, financial institutions had received 1.6 million applications for such assistance, with an approval rate of 95%. The assistance under these measures continue to be available to five million borrowers, if they need it. Furthermore, these measures will not adversely affect the ability of borrowers to seek new financing.

The dangers of using an Emergency Ordinance

I will not go into detail here and will instead leave it to the lawyers and legal experts to deliberate this further. However, under the Central Bank of Malaysia Act 2009 (CBA) and the Financial Services Act 2013 (FSA), the finance minister does not have the authority to instruct the banks to give an automatic loan moratorium.

On the topic of the potential use of an Emergency Ordinance, any new legislation has to be approved by the Cabinet and then presented to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong for His Majesty’s assent. Related to this, Section 4 of the Emergency Ordinance gives powers to the government to mobilise resources. But Section 5 clearly states the need to provide compensation to the party that has suffered losses. It is therefore a fallacy to posit that this can be done at zero cost to the government. Does this make financial sense, particularly in a resource-tight situation in a long-drawn war against an invisible enemy?

Clearly, there is a danger of using such powers indiscriminately, as a blatant disregard for contractual rights will have serious ramifications on future business and investments. Moreover, calls by various parties to do another round of automatic loan moratorium, justified by recent bank profits, sadly ignore the implications Malaysians will face in the longer term should the blanket automatic loan moratorium be reintroduced, to the detriment of the country and her people.

Closing

Relative to another round of blanket automatic loan moratorium, targeted repayment assistance is equitable, appropriate to the issue at hand and need-based while preserving the integrity of the financial system. Targeted help is given to the most affected and vulnerable, which complements the wider government approach of optimising resources for the long haul. It will also ensure that we can remain on a firm path to recovery that will raise the income levels and livelihoods of all Malaysians.

Tengku Datuk Seri Zafrul Aziz is Malaysia’s Minister of Finance

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.