This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on July 29, 2019 - August 4, 2019

THE crash-and-burn IPO of Pets.com at the height of the tech bubble in February 2000 was a seminal moment in global corporate history. The online pet food retailer had chalked up a mere US$619,000 in sales in the year ahead of its IPO, yet commanded US$330 million in market capitalisation at its listing debut. Selling products for a third of what you pay for them clearly does not make a viable business model. Not surprisingly, then, within weeks, Pets.com had gone bust and has been the butt of investors’ jokes ever since.

Two decades on, tech investors could be forgiven for a sense of déjà vu. Ride hailing giants Uber and Lyft listed earlier this year and are both currently still way underwater despite a bull market rally that has created new records. “Both Uber and Lyft have yet to convince investors that they have a path to profitability,” veteran tech fund manager Paul Meeks, who runs the Wireless Fund in Bellingham, a suburb of Seattle, Washington, tells The Edge Singapore.

Now, Wall Street is waiting for the most controversial IPO in years — the September listing of WeWork, the shared-office provider backed by Japan’s Softbank Group and its US$100 billion (S$136.4 billion) Vision Fund. With 750 locations in 125 cities in 36 countries, including Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Hong Kong, WeWork, whose valuation has ballooned to over US$47 billion, is by far the world’s largest tenant and one of America’s biggest unicorns, or a privately held tech firm valued at over US$1 billion. Already, it is the biggest tenant of commercial real estate in key financial centres such as New York and London as well as tech centres such as San Francisco.

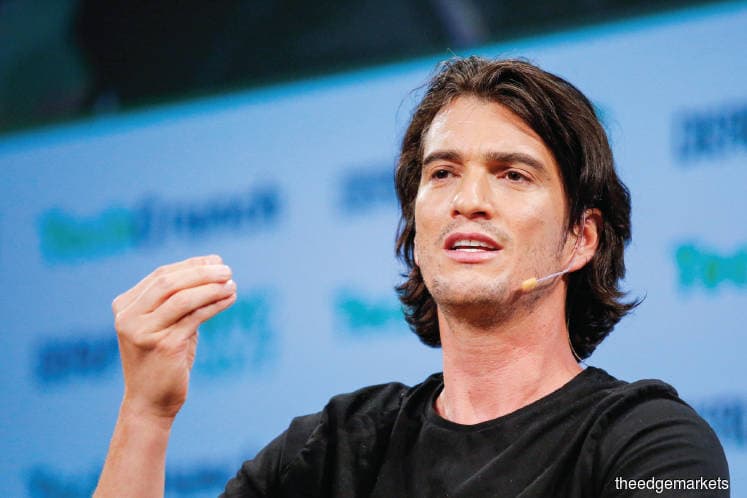

As it grows, New York-based WeWork has become one of the most recognisable — and divisive — start-ups in the world. Meeks, for one, believes WeWork is a real estate company that is just being valued like a tech unicorn. For its part, WeWork describes itself as a company that “provides shared workspaces for technology start-up subculture communities, and services for entrepreneurs, freelancers, start-ups, small businesses and large enterprises”. Though it may lack fancy proprietary software, WeWork claims to connect building owners with companies in need of office space. Its CEO Adam Neumann says WeWork leases commercial real estate because it just “happens to need buildings just like Uber happens to need cars, just like Airbnb happens to need apartments”.

Neumann, a charismatic Israel-born serial entrepreneur, co-founded WeWork nine years ago with architect Miguel McKelvey. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the duo leased a floor of a Brooklyn, New York commercial building, subdividing it and leasing it out to smaller firms. The We Company, as the larger group is known, has since expanded into other areas including WeLive, a co-living concept that offers furnished studio apartments, and WeGrow, an educational arm that includes kindergartens as well as a software coding academy.

WeWork owns no real estate; it just leases office buildings from property owners typically for five, 10 or 15 years, slices and spruces them up with nice interiors and fancy fixtures, adds sophisticated gyms and yoga studios, and re-leases them in smaller portions for shorter terms to companies that are looking for office space. In a world where businesses are increasingly looking to save costs and cut out the middleman, WeWork adds itself as an extra layer, charging a mark-up for all the bells and whistles. Put simply, there is no real value proposition in its business model.

“Strip away the barn-wood interiors, bean bags and espresso bars, and (WeWork) looks like a lot of other real estate companies,” notes Jeff Sonnenfeld, a professor at Yale University’s School of Management. “Is WeWork’s business model just a ‘house of cards’ fuelled by ‘Silicon Valley pixie dust’ as critics have claimed?” asks the New York-based venture capital research outfit CB Insight in a recent report. “Or do millions of square feet of office space, hundreds of thousands of members, and an ever-expanding repository of data add up to more than the sum of its parts?” The research firm argues that WeWork gives its tenants something that is ordinarily hard to find — a flexible space, on demand, with short-term leases.

That solves a problem that has particularly plagued fast-growing start-ups: finding a new office space, moving in, signing a long-term lease, remodelling and moving out to start it all over again somewhere else. “WeWork is vastly misunderstood,” says Pierre Ferragu, a tech infrastructure analyst for New Street Research in New York who covers Softbank. The way he sees it, commercial real estate in key cities is a business that is ripe for disruption. WeWork has a first-mover advantage and he notes, with Softbank’s backing, it now also has the capital to scale rapidly.

Not yet profitable

Still, nine years after it leased its first building, WeWork has yet to figure out how to make money from those barn-wood interiors, craft beer, yoga mats and dog treats, and justify the nice mark-ups on its leases. WeWork reported over US$1.9 billion in losses (up 103% over 2017) on US$1.8 billion in revenues last year, or nearly 34% below its own revenue estimates. (In comparison, rival IWG, formerly Regus, reported US$140 million in net profits on revenues of US$3.3 billion.) WeWork lost US$217,000 every hour last year. And as it grows its revenues, its losses are reportedly rising almost as fast. It is expected to post revenues of nearly US$3 billion this year. Losses for the current year could again rival its revenues, which would push total accumulated losses to nearly US$6 billion.

WeWork is losing money because it is spending on customer acquisition and retention, expanding its portfolio of office space as well as adding bells and whistles. Moreover, it can take months after a new lease is acquired to re-fit a building while not bringing in revenues. Detractors wonder whether its business model will work in a tougher economic climate. Companies are happy to pay for expresso bars or bean bags when the economy is doing well; it is unclear whether they will continue to fork out money for fancy offices in a downturn.

For now, banks like HSBC and Standard Chartered in Asia are happy to lease stylish, well-designed offices with pool tables, cappuccino and cookies in some cities, but will they continue to shun direct leasing from the likes of Sun Hung Kai Properties in Hong Kong or CapitaLand in Singapore and just rent from a middleman?

WeWork claims it has acquired tech companies that are helping it distinguish itself from other competitors. Last year, it bought Teem, a software and analytics provider that helps enterprises optimise their spaces and earlier this year, it acquired Euclid, an analytics platform that tracks and analyses how people move around physical spaces. That followed the acquisition of a building information modelling and architecture consultancy firm a few years ago.

It is unlikely these small acquisitions would be enough to help WeWork ward off competition, charge a mark-up, pare down costs and turn a profit. “Over time, WeWork’s ‘real-estate-as-a-service’ or its so-called REaaS offering, and trove of data on optimal office design could make its overall value proposition far more than a marketing ploy,” says a recent report by CB Insight. For now, WeWork needs more cash. Softbank’s CEO Masayoshi Son wanted the Vision Fund to write a big cheque to keep WeWork afloat, but late last year, Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund and Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Investment Co, the largest investors in the fund, balked at throwing more money at it. That forced Son to inject an additional US$2 billion in cash into WeWork earlier this year through Softbank Group itself. Softbank and its Vision Fund have injected a total of US$10.4 billion into WeWork, including buying out some of the earlier investors.

Conflict of interest

WeWork is now raising between US$5 billion and US$6 billion in additional debt just prior to its September IPO, which would raise another US$10 billion in equity, including a greenshoe option in what would be the biggest IPO of the year, overshadowing Uber’s listing in May that raised US$8.1 billion and the upcoming secondary listing of New York-listed Alibaba Group Holding in Hong Kong that is expected to raise US$9 billion. Raising billions in new debt just weeks before a multi-billion dollar IPO is rare, say analysts. WeWork is fast-tracking its IPO, which was originally not scheduled until later this year or next year, because it needs to raise more cash and management is worried that markets may be less friendly towards controversial IPOs the longer it waits.

WeWork’s rush to raise huge debt and equity comes at time when founder Neumann has been dumping his own shares, notes Sonnenfeld. Neumann has already sold over US$700 million in WeWork shares in recent weeks. The sale “indicates lack of faith in his own company while he prepares to hawk it to new investors”, the Yale professor says. Website TechCrunch recently reported that Neumann spent US$80 million on his six homes, including a 13,000 sq ft San Francisco crash pad with a guitar-shaped room. The media recently reported several key conflicts of interest, including Neumann earning millions of dollars as landlord of many of the buildings that WeWork has leased. “As he cashes out ahead of his own IPO, (investors) should worry whether WeWork really works — for anyone beyond its founder,” Sonnenfeld notes in a recent op-ed piece.

Detractors say WeWork is unlikely to command anywhere near the highest US$47 billion valuation that one option purchase put on it last year. The US$23 billion valuation at which Softbank bought out some early investors a few months ago is seen as more realistic. Yet, with a mounting debt load and a slowing global economy where companies may be less willing to pay a premium for dog treats and free lattes for employees, WeWork’s IPO is likely to struggle even with a strong backer like Softbank. It may have upended commercial real estate in key global cities, but WeWork needs to show that it has a viable business model before investors take it seriously.

Assif Shameen is a technology writer based in North America

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.