This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on January 6, 2020 - January 12, 2020

THE future is in coconut instead of oil palm.” My provocative statement at the Asian Strategy & Leadership Institute dialogue session “Poverty in Malaysia: Reality vs Perception” got a good response from the Minister of Primary Industries. We were discussing the matter of shared prosperity and poverty.

The minister and I are on the same page, that is, we are trying to figure out how to increase income for smallholders and farmers and how to achieve shared prosperity so that we can try to eradicate poverty.

Prices of commodities are low, yet essential food items are beyond their reach. We must solve the problems of smallholders, fishermen and farmers if we want to eradicate poverty.

So far, the policies formulated have failed to lift this group of people out of poverty. Subsidies do help but are not the answer in the long term. For sustainable, meaningful change, we need to increase their incomes. This can be done by educating them on the use and benefits of technology and precise agriculture.

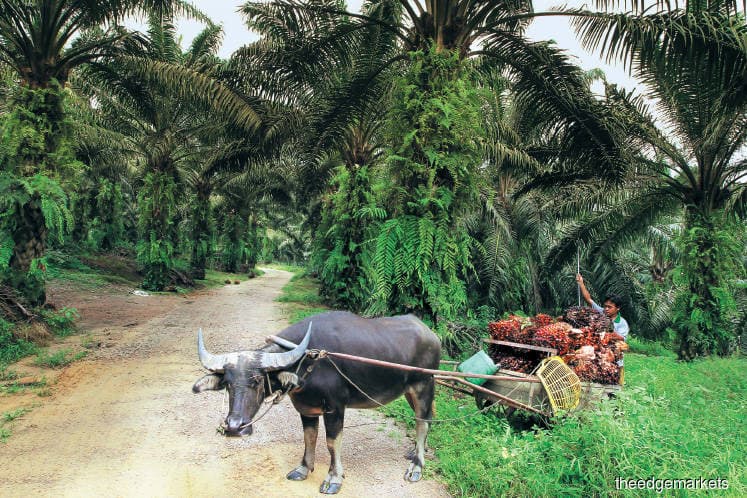

The oil palm industry must innovate and change if it is to survive in the future. There must be a constant drive for improvement, and none of the players in the industry can afford to stagnate.

What do we do with waste from agricultural activities, such as the leaves and trunks of palm trees? Much research is needed and there must be a change in mentality to adopt a circular-economy approach, or what many call “zero waste”.

What we currently view as waste should be kept within the economy and used to produce other products, for instance, people are using empty fruit bunches to create biofuel pellets, an alternative to charcoal, or to produce plywood and fibre mats.

More downstream activities (value-added products) are required, then there is a future. We need more companies that are able to produce products for Saji, Adela, Seri Pelangi and others to market. As productivity increases, income will increase as well. This will lead to a reduction in the poverty rate.

Currently, Malaysia remains as one of the top 10 coconut-producing countries in the world. Coconut is the fourth-most-important industrial crop in Malaysia after oil palm, rubber and rice. As I have highlighted before, coconut can be used in F&B, beauty products, handicraft, health products and others. Even the leaves, lidi, shell (tempurung) and coconut fibre (sabut kelapa) are in demand. Then, there is a new variety of dwarf coconut that produces more coconuts in a shorter period.

There is no single crop that is the answer to all our country’s issues. Rather, my point is that we should be looking at diversifying our crops and avoiding a national dependency on any one single crop. What the entire industry should be doing, regardless of whether it is commodities agriculture or agri-food production, is to be continually innovating and improving such that less and less resources are required and less waste is produced.

What will the next decade look like for the country’s agricultural sector? Let us look at the sector as a whole in the region.According to “The Asia Food Challenge: Harvesting the Future”, a report jointly produced by PwC, Robobank and Temasek recently, by 2030, Asia will have an additional 250 million people to feed (the equivalent of another Indonesia) and there will be a need for nutritious, fresh, safe and sustainably produced food to be delivered conveniently and on demand. As it is today, Asia struggles to feed itself. It is also too dependent on other regions for tech and food. It is a problem we can no longer ignore.

Asia’s current expenditure on food alone is projected to more than double to US$8 trillion by 2030. To meet the region’s agri needs for the future, it is estimated that an US$800 billion cumulative investment above existing levels will be required over the next decade. New and emerging technology will be needed to increase agricultural yields and nutritional value, while addressing the effects of climate change.

Coming back home, our food import bill is more than RM50 billion. In 2018, Malaysia ranked 40th among 113 countries in the Global Food Security Index. We need to address this and one way is through agriculture, more specifically, through agritech.

Agritech has also been identified as one of the key segments to uplift the livelihood of farmers and smallholders, who mostly are in the low-income household category, or B40. There is a positive correlation between an increase in agricultural productivity and economic growth.

If we can increase production to the point of increasing exports, we can also strengthen the ringgit and our economy in general. We will increase the incomes of farmers. We can decrease the cost of living and improve the quality of life.

Investment in innovation and technology is key for this sector.

• Modern and precise agriculture that holds the potential for these positive changes.

• Increase the productivity of the agriculture sector through technology, and thus reduce dependency on foreign labour.

• Malaysians are doing many exciting things here — there are drone manufacturers; students creating algorithms that help sort vegetables by quality and weight; and start-ups creating apps that help farmers move their vegetables quickly and efficiently along the supply chain. There needs to be some level of coordination from the government and its agencies to encourage and facilitate growth.

• It is also imperative that government agencies keep up with technological changes in the agri industry so that better policies can be formulated.

Our key advantage is the abundance of land, including idle agriculture land.

• The Department of Agriculture is making a good effort with its Idle Land Development Programme, but more people need to get involved and make use of the incentives available.

• I have also received feedback that getting access to idle land is quite difficult. Information on the Idle Land Development Fund must be made more easily accessible (that is, how to apply for funds); information on available idle land should be simplified — just as you can easily search for land to buy, there should be a clear directory for leasing/purchasing idle land.

• There is plenty of agricultural land available in Malaysia such that we do not need to clear any forests for the agricultural sector to move forward. However, the red tape involved in getting access to such land must be reduced and the process simplified if we wish for more people to take part in this industry.

• Furthermore, access to land must take into consideration the tenets of justice and equity — there are many issues surrounding the land rights of the Orang Asli. This is an issue that crops up throughout the developing world, and one that Malaysia must be proactive in addressing.

These are the reasons why I said that we need to make agri sexy — sexy through tech, sexy in the sense that money is made. We need to attract not just talent but investors to put their ideas and money in this sector.

Agri sector in the new decade

We want more people to get involved in agriculture, but to make this happen, the authorities must ensure that access to resources is equitable, and some long-standing practices may need to be reviewed. For instance, land rights, access to financing, and access to information and technical advice must be democraticised.

At the moment, Lembaga Pertubuhan Peladang (Farmers’ Organisation Authority) does a very good job providing technical advice, financing and even seedlings, but this will need to be holistically reviewed to ensure that it can keep up with demand as the sector expands. Furthermore, there may be a need for an “incubator” approach to encourage some smaller-scale farmers to engage with modern and precise farming practices, as usually costs are prohibitive to smallholders.

Water security will be a major issue, as agriculture is currently the single biggest user of national water resources. The sector must research and implement new methods of reducing water use, but at the same time, the government must plan ahead for increased water requirements in the future. Water is essential for citizens’ daily life, for manufacturing, for tourism, for businesses and, of course, for agriculture. We experienced many water cuts last year and, of course, in pockets of Malaysia, particularly for rural and indigenous communities, many still do not have consistent access to clean water. This must change.

Conservation will be another big issue. As we all know, monocropping can lead to massive biodiversity loss, and we have seen vast areas of forest land cleared, burnt or pillaged for the purpose of obtaining forest products or planting new crops. What we must bear in mind is that plenty of agricultural land is already available and both federal and state governments must make it easier to access designated agricultural land. No further forest land should be cleared for the purpose of agriculture.

In fact, there should be a clear plan for reforestation and restoration of agricultural land that is no longer productive. Forests are important carbon sinks and Malaysia as a megadiverse nation must have clear guidelines on sustainable practices to protect this natural resource. Rainforest and peatland areas should be gazetted, while ensuring that access to readily available agricultural land is made easier and less complicated for those who want to work it. There are already various policies and guidelines in place, but implementation will require further cooperation between the various agencies and ministries involved.

We should also be looking into carbon farming as it may be the industry of the future. It is the process of changing agricultural practices or land use to increase the amount of carbon stored in the soil and vegetation (sequestration) and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from livestock, soil or vegetation (avoidance). Carbon farming potentially offers landowners/farmers financial incentives to reduce carbon pollution. For example, Australian carbon farmers are now earning income for cutting greenhouse gas emissions or sequestering carbon.

The Australian government has created the Emission Reduction Fund to provide businesses with the opportunity to earn Australian carbon credit units for every tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent a business stores or avoids emitting through adopting new practices and technologies. In the private sector, a US-based start-up is also offering financial incentives of US$15 per tonne of carbon dioxide sequestered.

In addition to earning additional income, farmers also find a lot of extra benefits from this process, such as better animal production, improved soil health, water management and biodiversity. Carbon farming is under the umbrella of regenerative farming, which also includes practices such as agroforestry, crop rotation, permaculture and the principles of holistic agriculture management. These practices are intertwined and should be studied in the context of the Malaysian agricultural industry to ensure that the best practices are implemented here, for the benefit of our farmers and Malaysians as a whole.

The local agriculture sector is too convoluted owing to bureacracy. It is hard to break into the sector unless you have experience and contacts, which holds back many aspiring young farmers. I hope the relevant authorities will review their practices to ensure a simpler and more efficient process. Sometimes, people tend to forget that time is also a resource, and agriculture in Malaysia currently demands far too much time to jump through various hoops.

On the commercial side, farmers big and small will need to embrace a change in techniques and learn new things. Traditional knowledge is of course still important, and practitioners should find a way to create synergy between old and new techniques to get the best out of them. I said this before and I will say it again: We must embrace technology as, without it, we will be left behind.

On a larger scale, I would like to see more focus on data protection. As I said, information must be easily accessible and understood; however, there must also be stringent protection in matters of national security as well as individual privacy. Some data points related to agriculture are issues of national security, for instance, protecting our nation against threats of bioterrorism, climate change and food scarcity, and the data is therefore highly sensitive and must be treated as such.

The European Union has enacted the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which governs data protection and privacy for all European citizens, affecting any business offering services to users in the region. In May 2019, Thailand came up with its own version, the Personal Data Protection Act, which means that if we wish to access that market, we will need to enhance our data protection practices as well.

Tun Daim Zainuddin is a former finance minister and member of the Council of Eminent Persons

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.