This article first appeared in The Edge Financial Daily, on February 22, 2016.

GERMAN Chancellor Angela Merkel has often made eloquent arguments to persuade the European Union’s (EU) fractious members to put the bloc’s interests above their own. Now, in deciding whether a new natural-gas pipeline should be built from Russia to Germany, she should take her own good advice.

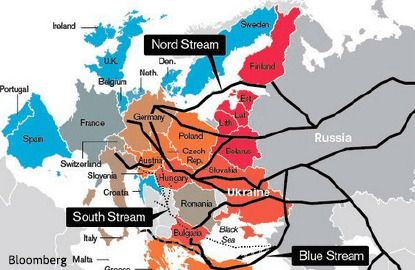

Nord Stream 2 would double the capacity of a pipeline that brings natural gas directly from Russia to the German coast, across the Baltic Sea. Merkel says it is a commercial project and therefore none of her business. Yet the project makes little commercial sense. At a cost of roughly €10 billion (RM46.84 billion), it would expand pipeline capacity at a time when half of the existing gas-transit capacity from Russia to the EU is unused.

And although native EU gas production is falling, adding this much capacity from Russia for future use runs counter to the EU’s policy of diversifying energy suppliers.

For Europe, though, the question of whether to build Nord Stream 2 is mainly a political one. The original pipeline, completed in 2011, was already divisive because it helped Russia to begin circumventing Ukraine’s transit network, which feeds the EU via its ex-Soviet bloc members. Poland’s foreign minister at the time, Radek Sikorsky, likened Nord Stream to the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, under which Hitler and Stalin secretly agreed to carve up his country.

The pipeline was built anyhow. But that was before Russia annexed Crimea, and sent its tanks and troops into Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region. Now Russia is pushing to expand Nord Stream’s capacity before the transit contract between Ukraine and Gazprom, Russia’s state gas company, expires in 2019. At that point, Gazprom would like to be able to send gas to Europe without going through Ukraine at all.

Without the gas-transit business, Ukraine would not be able to maintain its Soviet-era pipeline network. It would lose US$2 billion (RM8.42) a year in revenue (1.5% of the country’s gross domestic product). And it would no longer be able to deter Russia from cutting off Ukraine’s own gas supplies by threatening to siphon gas that’s bound for the EU.

Nord Stream 2 would also end the transit fees now paid to Eastern bloc members along the route from Ukraine. A group of countries including Poland, the three Baltic States, Hungary and Romania have complained. They say Nord Stream 2 would undermine their ability to negotiate a fair gas price with Gazprom and reduce their energy security, even as it boosts Germany’s.

Merkel is surely under domestic pressure to let the pipeline go ahead. Nord Stream 2 would turn Germany into the dominant natural gas hub for Europe, bringing financial and strategic benefits. Yet Germany’s gain would come at a cost to others and to the EU as a whole. By putting narrow national interests first, Merkel undermines her efforts to get Eastern Europe to ignore their own and agree on a common solution to the Syrian refugee crisis, to back reforms that will help keep the UK in the bloc, and to maintain economic sanctions on Russia until it has withdrawn its tanks and troops from Ukraine.

At least two of those goals — refugees and Brexit reforms — will be up for negotiation at the EU summit that starts on Thursday. By sacrificing a pipeline that only Russia truly needs, Merkel could help secure goals that are far more important for all of Europe. — Bloomberg