This article first appeared in Digital Edge, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on May 17, 2021 - May 23, 2021

The internet went into a frenzy when musician 3LAU made US$11 million (RM45.3 million) from the non-fungible token (NFT) of his album and other digital goods in March. Later that month, digital artist Beeple sold his NFT artwork for US$69 million, the highest price ever fetched by a living artist after Jeff Koons and David Hockney.

Local artists such as Fariz Hanapiah are observing this trend with barely suppressed glee as it would mean additional revenue streams for people like them. Fariz, a creative director at Experiential Design Team (EDT), first heard about NFTs when he attended a motion design class in Tokyo, where Beeple was one of the guest speakers.

“The whole conversation [in the motion design class] revolved around cryptocurrencies and the arts,” says Fariz, adding that it was especially interesting to him because he had been into cryptocurrencies for a long time.

This is all well and good but, while the three-letter abbreviation has been bandied about with increasing frequency (usually in connection with vast sums of money raised), many do not know what it means.

T M Lee, co-founder of homegrown cryptocurrency ranking website CoinGecko, explains, “Digital currencies and other cryptocurrencies — including Bitcoin — are all fungible, which means you can exchange one for another and it is all the same.

“NFTs though, are non-fungible, which means one cannot be exchanged for another. You may compare it to collectible cards, which have different values based on their rarity. You wouldn’t be able to exchange an ordinary card for a rare one. In the same way, NFTs are digital assets with unique characteristics, which give them all different values, making them non-fungible.”

Commonly, NFTs come in the form of virtual art pieces, a digital collectible or even a tweet. Does owning an NFT make any difference since we can all easily get access to the same thing in digital form?

Darren Lau, an analyst at blockchain investment and advisory firm The Spartan Group, says, “People would say I can take a picture of the Mona Lisa, but the picture is not equivalent to the actual painting of the Mona Lisa. In that sense, even though you can screenshot an NFT, you still do not own a copy. The only way to own an NFT is to buy it through a transaction on the blockchain, then you have the public record of ownership.”

Opening doors of opportunities

The rise of NFTs opens up a new market for the digital art industry as it has always been a struggle for digital artists to sell their works, says Fariz. “The artists in Malaysia have struggled a lot and their sales channels are quite limited.”

Artists may benefit from the royalties they receive from the sale and resale of their work through NFTs. “Imagine if you make an artwork and it is resold 10 times, and you earn royalties from all 10 transactions. That would be good enough for these artists to keep making art,” he points out.

A trendwatcher in the cryptocurrency industry, Lee observes that people in Malaysia are now more receptive to NFTs than before. “Last year, I asked content creators, artists and photographers about NFTs, but a lot of them were not interested. I think they were sceptical about such trends.”

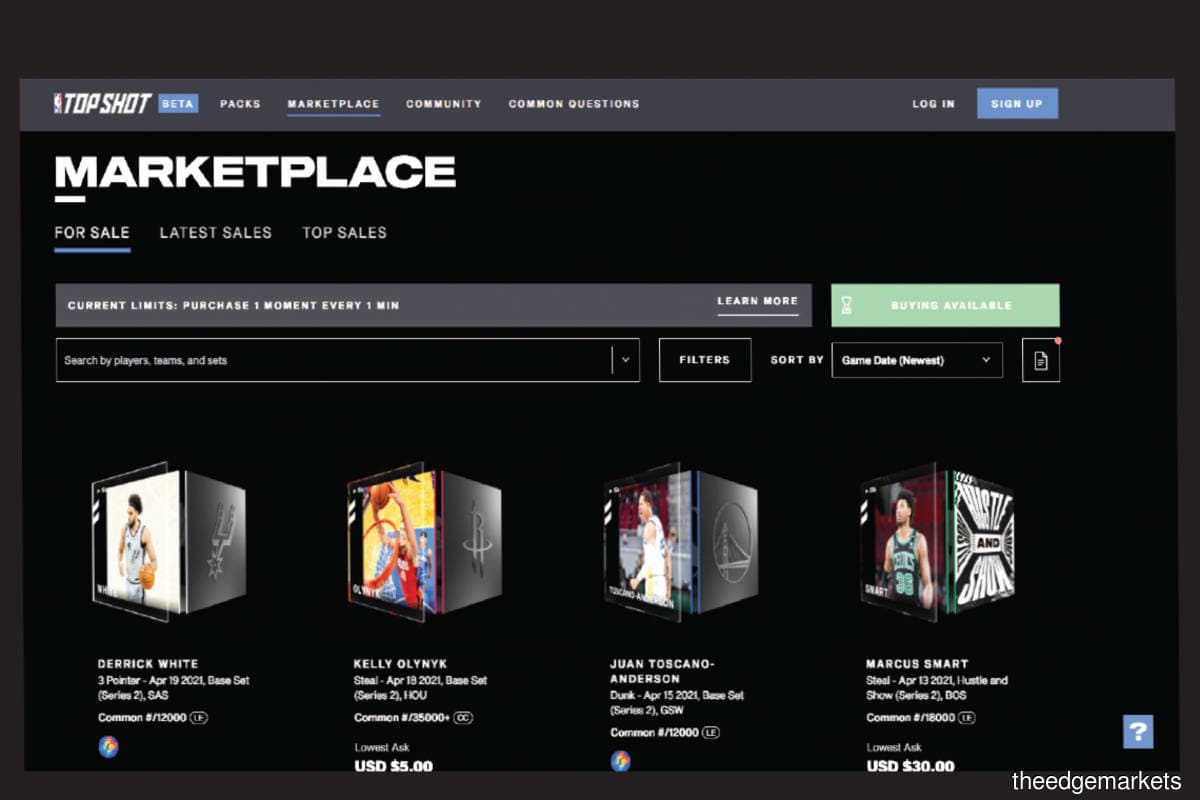

How things have changed. Lee notes that local artists are now open to exploring how NFTs can be used either as an additional revenue stream or a new way to express their creativity. “When you put up NFTs in the marketplace, it can be purchased by anyone in the world.”

Although the typical buyers of NFTs are either wealthy individuals or casual collectors, he points out that most of the people who own NFTs are the early crypto adopters. “They know how to buy from the marketplace and how to store NFTs safely. It requires knowledge to buy NFTs and keep them.

“Of course, now there are marketplaces that attempt to bridge the gap. They sense that you don’t need to know everything about crypto, and you can even buy NFTs with your credit card.”

Artists can choose different marketplaces to “mint” their artworks, meaning that their paintings are put up as part of the blockchain. There are curated marketplaces such as SuperRare and Nifty Gateway that interview the artists before minting their artworks, says Lee.

The bar to enter one of these curated marketplaces is set pretty high, so new artists would probably opt for the more open marketplaces such as OpenSea and Rarible, where anyone can put up their artwork without the need for an initial interview or evaluation, he adds.

In Malaysia, artists use NFTs not only to make money but also to protect their digital art, using the tamper-proof feature of blockchain. “I have a lot of digital art and I want to archive my work. Turning them into NFTs allows me to protect my work,” says Fariz.

A modicum of risk

Although there are many stories out there about the insane amount of money brought in through the sale of NFTs, many artists are intimidated by the high cost of minting their work. “Sometimes, it costs up to RM100 to mint a single digital artwork. Some may say it is incomparable to the amount of money that you can earn from the small amount of artworks. The minting cost is high simply because the Ethereum network requires a lot of energy,” says Fariz.

Like other cryptocurrencies, NFTs elicit environmental concerns because of their high energy use, but Fariz insists that there are solutions to offset the harm. For instance, Jason Bailey — founder of open source bounty Green NFTs — raised more than US$34,000 to reduce the ecological impact of these tokens.

The other problem is being ignored by the market. Fariz points out that some artists put up their NFTs and nothing happens. These artists, he points out, need to get out there and work on their personal branding and creative storytelling. Sales will not happen automatically as a matter of course.

“If you are an artist, you need to be identifiable to the buyers, as the artist is also part of the artwork itself. People won’t buy art for its own sake. It’s also about the artist and what the art stands for,” says Fariz.

For those open marketplaces, although they allow everyone to post their NFT, their lack of scrutiny or evaluation makes the artists who post their work there vulnerable to intellectual property (IP) theft. “Some platforms would want the artists to validate themselves to make sure that these artists are the real owners before allowing them to post the artworks online. But here [open marketplaces], there are artworks uploaded without the real artist knowing about it,” he says.

All three — Lee, Lau and Fariz — agree that NFTs in Malaysia are still at the nascent stage. But they are hopeful about the future of this particular form of digital tokens, especially in relation to the local digital art market.

“We need a platform that can both protect the artists and enliven the industry. NFTs open up a new way for digital artists to make money from their work. Before, it was difficult for them to even get into an art gallery,” Fariz points out. “NFTs are one way to validate the artwork. Buyers would be able to know that what they are buying are genuine digital products and this creates value for digital art. [In Malaysia,] the success stories about NFTs are not yet there, but they are coming.”

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.