This has been a tumultuous year full of black swans. No one expected Donald Trump to win the US presidential election or the UK to vote to leave the European Union.

Earlier this year, the world was hit by yet another mosquito-borne infection — the Zika virus — prompting the World Health Organisation to declare a public health emergency. Terrorist attacks, the continuing global refugee crisis, the war in Syria and the generally unsettled state of global politics have left the world in more turmoil than before.

It is perhaps fitting that with so many things to worry about, no wealth management or investment books made it to the best-seller list. Most of the books listed on top 10 lists had to do with trying to guide people on the right attitude to face what looks like another financial crisis or explaining some of the forces behind the current political shifts.

With the ringgit in freefall and the stock market moribund at best, who are the sages we will look to for guidance? Unlike in previous years, where there was a plethora of choices, the pickings are pretty slim this year. We expect this to change next year as pundits rush to analyse the perplexing events this year and put them into perspective so we know how to view them, and where to put our money.

To end the year on a reflective note, the Personal Wealth team has come up with a review of some of the notable books that offer an insight into what is actually happening and how to cope with the situation.

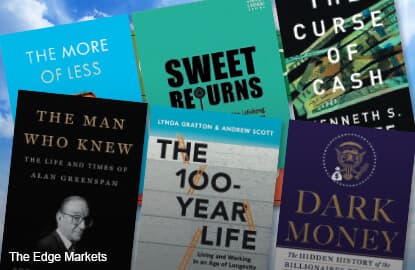

The More of Less: Finding the Life You Want Under Everything You Own

by Joshua Becker

This resonates with the “times are hard” and “tighten your belt” mantras we seem to be hearing more of these days. Joshua Becker advises readers to step out of their consumerist trance and strip themselves of the physical (and oftentimes emotional) baggage that has been weighing them down.

The book starts with an epiphany in his garage, where he realises that all his “stuff”, rather than making him happy, is actually doing the opposite and he rushes to tell his wife that they do not need to own so many possessions. They begin to sell, give or throw away what they do not need, stripping down to what, for them, is a comfortable minimalism.

Becker started a blog to let the rest of the family know what he was doing and the blog went viral. That was when he realised that there was a great hunger for minimalism in a country where people were snowed under by their stuff.

The rest of the book is a how-to guide for those who want to become a minimalist. Becker points out that when you decide to dump the unnecessary stuff and not take on anymore, you get more time and energy, money, generosity and freedom. At the same time, you have fewer distractions and less stress as well as a lower impact on the environment. Also, by not having so much, you free up your cash to buy only high quality things.

“Minimalism is not necessarily the same as frugality. It is a philosophy recognising that owning more stuff is not better; owning better stuff is better,” says Becker.

And perhaps your path to financial freedom will not come from earning more, but by owning less.

Sweet Returns: Sustainable Lifelong Investment Treats

by Joyce Chuah

This is the only local book on our list and it is not on any best-seller list. It is also the only personal finance/wealth management how-to book on our list.

Joyce Chuah exemplifies the typical Penangite — frugal to a fault. She took minibuses to work, standing in her high heels and skirts and clutching the handholds (she could never get a seat). She also rigorously budgeted every sen, putting her entire bonus, year after year, into fixed deposits.

She describes herself as being addicted to liquidity and even though she was working throughout most of the stock market super boom, she did not put any of her money in the market until 1996, a year before it crashed.

Chuah describes her journey from a saver to an investor, letting you in on all the research she has done in the different market instruments in clear, highly readable prose. She breaks down very complex concepts for the reader, hand-holding them along the way.

As she became a financial planner in 1998, during the worst of the Asian financial crisis, she has some useful advice about keeping your head in the present market. “During periods of decline, which stir up fear, investors have a higher tendency to lose their capital as they feel pressured to sell. To make matters worse, selling usually occurs at the wrong time, after experiencing significant investment losses. When fear takes over, any logic is gone. Emotions take centre stage instead in your investment journey.”

She goes into the psychology of an investor, pointing out their mistakes along the way, especially the mistake of realising losses at the worst possible times and placing the redeemed proceeds into low-returning instruments. “This means you will almost never recoup the realised losses,” she says.

Her much-overlooked book (it is part of the Diet for Success Series, which was launched to empower readers with financial literacy) will be an increasingly important one as investors negotiate the roller-coaster ride that is already happening and the one that is to come.

The Curse of Cash

by Kenneth S Rogoff

This book was longlisted for the Financial Times and McKinsey Business Book of the Year 2016. Ben Bernanke says the world is drowning in cash. And it is making us poorer and less safe. In The Curse of Cash, Kenneth S Rogoff, one of the world’s leading economists, makes a persuasive and fascinating case for an idea that until recently would have seemed outlandish — getting rid of most paper money.

There is so much paper money flooding the system. In the US alone, it stands at a record US$1.4 trillion, mostly in US$100 bills. And a large part of this cash is feeding tax evasion, corruption, terrorism, the drug trade, human trafficking, and the rest of a massive global underground economy.

Rogoff offers a plan for phasing out most paper money while leaving small-denomination bills and coins in circulation indefinitely. The book also addresses the issues the transition will pose, ranging from fears about privacy and price stability to the need to provide subsidised debit cards to the poor.

Not everyone is fan. Jim Rickards, author of another best-selling personal finance/wealth management book entitled The Road to Ruin had this to say about it.

“The real reason the power elite wants to abolish currency is so they can force everyone into the digital banking system. Once everyone is forced into these banks, it is easy to impose negative interest rates to confiscate your money.

“Paper money is the best way to avoid negative interest rates. So, paper money must be abolished before the elite plan can be implemented. A cashless society forces everyone into digital bank accounts that can be taxed, frozen or stolen by negative rates. Getting savers into digital accounts is like rounding up cattle for slaughter.”

Strong words. We suggest you read both Rogoff and Rickards and make up your own mind about it.

The 100-Year Life: Living and Working in an Age of Longevity

by Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott

People are living longer. And for many, that is not a reason to celebrate. In fact, insurance companies have a term for outliving your assets — longevity risk. One anecdote encapsulates this risk: a man tossing and turning in bed because he had planned to have his assets last until he was 85, and was now 83, still in good health and not look likely to pop off anytime soon.

The majority of Generation Z are expected to live to be centenarians (although this conflicts with other research that says this generation will be the first to not outlive their parents due to processed food and genetically modified products flooding the market). The associated policy changes of a society composed of 100-year-olds are daunting and would need a radical rethink of traditional patterns of education, career development, employment and retirement.

We will also have to come up with viable solutions for the likely associated pensions and savings crisis. All the traditional safeguards such as family support systems or pensions that will last you until you die are no longer there. This means working longer, not out of choice, but of necessity.

Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott, who are professors of management practice at the London Business School, give the following example. They say if your life expectancy is 100 and you want a pension that is 50% of your final salary and save 10% of your earnings each year, you will not be able to retire until you are in your eighties. So, people with 100-year life expectancies must recognise that they are in it for the long haul and get an early start on arranging their lives accordingly.

The authors advocate the idea of a multistage life, with repeated changes of direction and attention. Material and intangible assets will need upkeep, renewal or replacement. Skills will need updating, augmenting or discarding, as will networks of friends and acquaintances. Earnings will be interspersed with learning and self-reflection.

This is a good book for those who are younger and actually have the time to plan for these different stages.

The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan

by Sebastian Mallaby

Why would you be reading a book about Alan Greenspan today? How would it be relevant when he retired as the chairman of the US Federal Reserve 10 years ago, after 20 years in that role? Maybe because, 10 years later, we are still dealing with the effects of the policies he put in place.

This book traces the life of Greenspan, pushing him forward as “the man who knew” because of his mastery of data: “He was the kind of person who knew how many thousand flat-headed bolts were used in a 1964 Chevrolet and what it would do to the economy if you took out three of them”, and his astute predictions of how increasing or decreasing interest rates would affect inflation.

In his autobiography, The Age of Turbulence, published just before the global financial crisis, Greenspan argued that the aftermath of the Sept 11 attacks were enormously important to the US economy, in that it made it more resilient. The former disciple of Ayn Rand (author of Atlas Shrugged and founder of Objectivism, the philosophy of rational self-interest) went on to say that we are living in a global capitalist economy that is vastly more flexible, resilient, open, self-correcting and fast changing than it was even a quarter century earlier.

And then the global financial crisis happened. So, the question remains, if Greenspan was the man who knew, why didn’t he foresee this crisis or do anything to stop it?

Sebastian Mallaby lets him off easy, suggesting that he became imprisoned by his reputation. His cult status had come to depend upon continual growth, exuberant finance and low unemployment and he was reluctant to rock the boat and introduce legislation that would have curbed irrational exuberance and either prevented or mitigated the crisis.

For an alternative point of view on Greenspan that is not so kind, read the chapter on him in Matt Taibbi’s Griftopia. Taibbi is a writer for Rolling Stone magazine. The chapter on Greenspan is titled: The Biggest ***hole in the Universe. Unlike Mallaby, Taibbi does not clear him of complicity in the lead-up to the financial crisis. It is an interesting counterpoint.

Dark Money: The Hidden History of Billionaires Beyond the Rise of the Radical Right

by Jane Mayer

You should read this book (it makes for good, if depressing, holiday reading) if you want to understand how the US political system got hijacked by the Radical Right. Jane Mayer answers some key questions: Why is the US living in an age of profound economic inequality? Why, despite the desperate need to address climate change, have even the modest environmental efforts been defeated again and again? Why have protections for employees been decimated? Why do hedge fund billionaires pay a far lower tax rate than middle-class workers?

She does not think it was because of a popular uprising against “big government”. Instead, Mayer, a staff writer for The New Yorker, shows how a network of exceedingly wealthy people with extreme libertarian views (those who believe in the doctrine of free will and self-governance) bankrolled a systematic, step-by-step plan to fundamentally alter the US political system.

Mayer believes that Charles and David Koch, the enormously rich proprietors of an oil company based in Kansas, and a small number of allied plutocrats have essentially hijacked US democracy, using money not just to compete with their political adversaries, but to drown them out.

US journalist and political commentator Bill Moyers quoted the following extract from an email by one of his friends, a long-time public servant and experienced cultural and arts administrator, on reading the book: “Her thesis, impressively backed by careful research and a wealth of rich anecdotes, is that the Kochs and their network of billionaires have ALREADY bought the American political system: the House, the Senate, many state legislative and Congressional redistricting, and significant beachheads in the American higher education.

“Further, she argues that what we once knew as the Republican Party is, in effect, being supplanted by a private party of billionaires who use its machinery but have little use for the traditional political tools of compromise and negotiation. Why? Because they want what they want, hate government and do not really care if it works.”

Mayer spent five years conducting hundreds of interviews and scouring public records, private papers and court proceedings. The people she wrote about set private investigators on her trail to come up with evidence to support a charge of plagiarism, that she was stealing from the work of other writers for her book. She was alerted and the case collapsed even before it got off the ground.

The book itself is shocking enough, where conspiracy theory is the new normal today, but the drama surrounding the book is fodder for a blockbuster.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.