This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on August 8, 2022 - August 14, 2022

IN the past fortnight in parliament, several elected lawmakers rightly asked about the state of the country’s finances, wanting not only an update on the trillion-ringgit debt burden and debt servicing capability but also the size of financial reserves. The latter may have been spurred by active social media sharing of Singapore having S$1.57 trillion (US$1.1 trillion or RM5 trillion) “reserves” despite having little natural resources — incidentally, with the ringgit weakening past 3.23 to new all-time low levels versus the Singapore dollar in the run-up to the city-state’s 57th national day celebration on Aug 9. The S$1.57 trillion shared on social media is not the actual size of Singapore’s financial reserves, but more on that later.

While Malaysia is in no immediate danger of defaulting on its loan obligations and becoming the next Sri Lanka, the fact that interest rates are rising at their fastest pace in two decades in most of the developed world means that debt will become more expensive to service — racking up pressure for greater revenue generation capabilities and higher spending efficiencies.

And not only is Malaysia among the majority of countries that had little choice but to accumulate more debt to save lives and livelihoods during the Covid-19 pandemic, official data shows that the country has been rolling over its debt. That means it is meeting all interest obligations as well as principal payments when they are due, but it is taking on new debt to do so instead of paying it down.

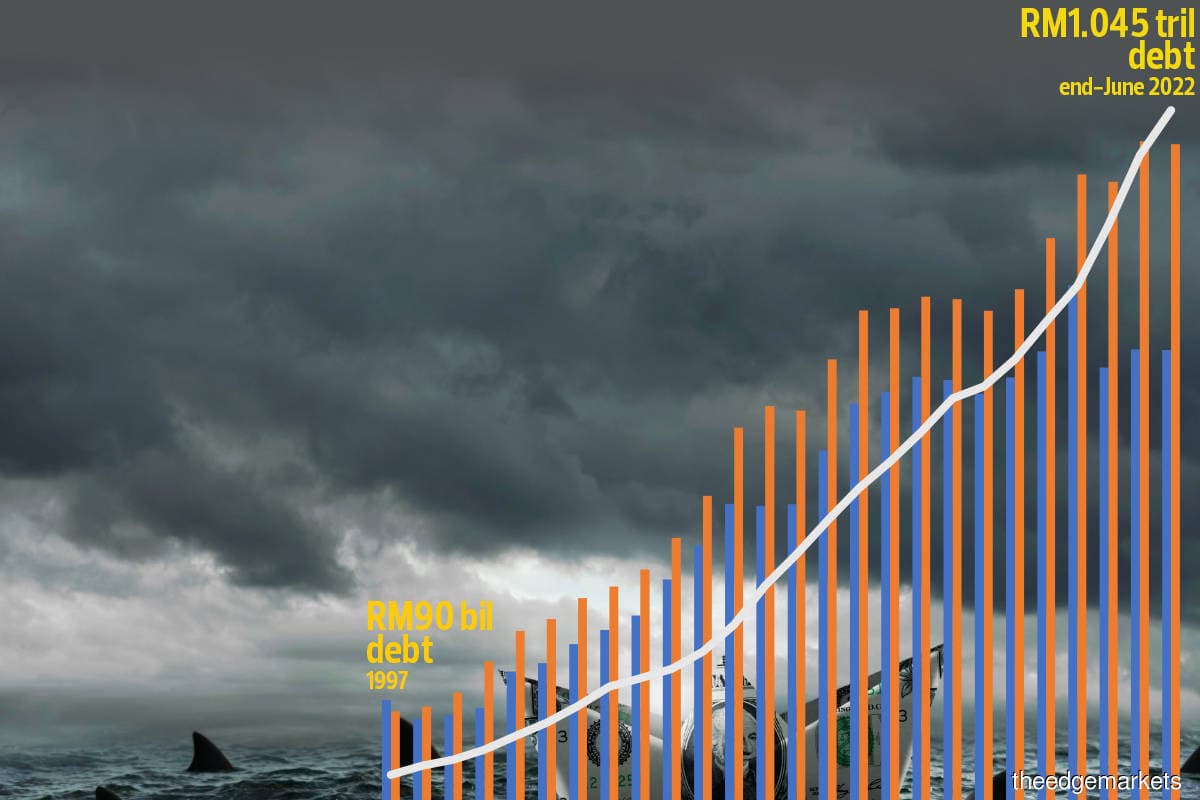

Spending in excess of revenue every year since 1998 by issuing debt, Malaysia’s direct federal government debt had previously climbed by roughly a quarter of a trillion ringgit every six years — rising from RM242 billion in 2006 to RM502 billion in 2012 and RM741 billion, or just over 51% of gross domestic product (GDP), in 2018.

Direct federal government debt stood at RM824 billion as at end-March 2020, the same month Malaysia implemented the first Movement Control Order (MCO) after Covid-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020. The tally stood at RM1.045 trillion, or 63.8% of GDP, as at end-June.

That means that instead of six years, another quarter of a trillion in debt had been accumulated in just over half the time (2019 to early 2022) (see Charts 1 and 2).

100% debt-to-GDP within 15 years?

In reply to a question from Ipoh Timur member of parliament and chairman of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) Wong Kah Woh, Finance Minister Tengku Datuk Seri Zafrul Aziz told parliament on Aug 1 that direct federal government debt of RM1.045 trillion excludes RM32.08 billion outstanding principal and interest for three 1Malaysia Development Bhd (1MDB) (US$1 = RM4.50) papers. It also excludes RM8.78 billion principal and interest for loans for the Suria Strategic Energy Resources Sdn Bhd (SSER) petrochemical and gas pipeline projects in Sabah taken from the Export-Import Bank of China (RMB1 = 65.88 sen). While not asked for one, Zafrul did not volunteer a figure for Malaysia’s total debt obligation currently.

From official data releases, however, it is known that direct federal government debt had risen from RM979.8 billion as at end-2021 to RM1.0058 trillion, or 61.4% of GDP, as at end-March this year. Debt directly guaranteed by the federal government was RM312.7 billion, or 19.1% of GDP, as at end-March 2022.

In January 2018, The Edge had calculated that Malaysia’s federal government debt could hit RM1 trillion by 2021, RM2 trillion by 2028 and RM3 trillion by 2032 if borrowings continued to grow at an average of more than 10% a year — the rate it had been growing the past 20 years between 1997 and 2017 (see “Debt surge — Should we worry?”, The Edge, Issue 1196, Jan 8, 2018). Back then, the headline debt figure was RM687.43 billion as at end-September 2017 compared with RM91 billion in 1997.

If Malaysia’s direct federal government debt continues to grow around 8% a year, which is the average annual growth rate for the past decade, direct federal government debt will hit RM2 trillion by 2030, RM3 trillion by 2035 and RM4 trillion by 2039, back-of-the-envelope calculations show. If that happens, the debt-to-GDP ratio could cross 70% of GDP by 2024, 80% of GDP by 2029, 90% of GDP by 2033 and 100% of GDP by 2037, even if GDP growth averages 5% a year, simple workings show (see Graphic 1).

That simplistic working has yet to take into account higher debt servicing costs as interest rates rise.

Higher rollover cost

The saving grace is that some 97% of outstanding federal government debt of RM1.0058 trillion as at end-March is ringgit-denominated. Only 1.8% was in US dollars while 1.1% was in yen, according to Bank Negara Malaysia data (provided in ringgit equivalents).

Still, it will become more expensive as the government rolls over its borrowings with new debt paper at higher interest cost as most of the world, led by the US Federal Reserve, exits the sub-zero and ultra-low-rate regime.

Investors are already demanding higher interest rates. The coupon rates for the benchmark 10-year Malaysian Government Securities (MGS) have risen from as low as 2.632% in October 2020 to 3.582% in January this year. New paper will have to offer higher coupons, with 10-year MGS yields around 4% at the time of writing.

Yields for government debt were around 3% for one-year paper, 3.3% for two-year paper, 3.6% for three-year paper, 3.8% for five-year paper, 3.95% for seven-year paper, 4.2% for 15-year paper, 4.4% for 20-year paper, 4.5% for 25-year paper and 4.6% for 30-year paper, data on Bond Pricing Agency Malaysia (BPA) showed at the time of writing (see Chart 3).

A RM1 trillion debt burden means every 10-basis-point (bp) increase in the average borrowing cost could cost RM1 billion a year and a full percentage point RM10 billion a year, back-of-the envelope calculations show.

Forty-seven per cent of paper maturing within five years

According to Bloomberg data at the time of writing, the Malaysian government had RM1.09 trillion debt paper issued with an average maturity of 8.6 years and 4% coupon per year.

Even if Malaysia does not borrow another ringgit, interest payments on RM962 billion MGS and the shariah-compliant Malaysian Government Investment Issue (GII) alone total RM368 billion from August 2022 through 2052, Bloomberg data shows. Other debt paper includes Treasury bills, government housing sukuk (SPK) as well as offshore borrowings.

About 15%, or RM163 billion, of the debt paper (MGS and GII) will mature within two years (by end-2023); 31%, or RM337 billion, are set to mature within three years (by end-2025); and some 47% or RM508 billion of the MGS and GII mature within five years (by end-2027), Bloomberg data shows (see Chart 4).

Some RM110.4 billion, or 11%, of Malaysia’s RM1.058 trillion debt paper (as at end-March 2022) matures within a year; and 28%, or RM276 billion, are maturing within three years. Just under 43% will mature within five years, compared with 57% or RM578 billion above five years, Bank Negara data shows.

According to Bloomberg data, about 20% of existing MGS and GII are due within five to 10 years (2028-2032), 23% within 10 and 20 years (2033-2042) and just under 10% within 20 to 30 years (2043-2052).

Simply put, about half of the current debt paper is likely to be rolled over at higher rates within five years — barring an about-turn in the direction of global rates.

Sizeable interest payments

Debt servicing charges, which made up 8% of federal government revenue in 2008, had surged past the 18% mark in 2021.

Including this year’s estimate of RM43.1 billion, Malaysia would have spent RM468 billion on interest payments for its debt alone since 2000. Debt service charges could reach RM46 billion in 2023, back-of-the-envelope calculations show.

If so, interest payments for just next year alone would be more than 90% of the cost of the overall cost to build the Mass Rapid Transit Line 3 (MRT3) that Zafrul said could cost RM50.3 billion overall (RM34.2 billion for construction; RM8.4 billion for land acquisition; RM5.6 billion for project management; and RM1.9 billion in other costs).

At RM43.1 billion, interest payment on federal government debt for 2022 alone is equivalent to RM3.59 billion per month, RM828.8 million per week, RM118.08 million per day, RM4.92 million per hour, RM82,002 per minute and RM1,367 per second. It is also enough to give RM1,318 to every man, woman and child in Malaysia, including non-citizens (see Graphic 2).

Interest payments on Malaysia’s direct federal government debt alone is more than half of development expenditure since 2014 and has hovered around 60% of development expenditure since 2015 as total debt burgeoned, official figures show (see Chart 5).

Interest payments of RM43.1 billion estimated in Budget 2022 would be 57% of the RM75.6 billion earmarked for development expenditure, if the actual amount is not cut owing to the outsized subsidies bill of nearly RM80 billion, of which only RM31 billion had been planned for.

The RM43.1 billion debt service charges estimated for 2022 are more than double the RM18.18 billion earmarked for education, health and housing under development expenditure for this year.

Debt service charges, which have surpassed 10% of revenue since 2014 and burgeoned to 15% of revenue since 2020, could make up 20% of revenue by 2027 if allowed to grow at the current 10-year average growth of 8% per year, while revenue continues to grow at an average of half that pace, simple workings show.

Worse still, if emoluments as well as pension and gratuities — which already make up half of federal government revenue budgeted for 2022 this year — continue to grow at the rate they have grown on average in the past decade, these two expenses could take up 60% of revenue by 2031 and 70% of revenue by 2038. At that trajectory, emoluments, pension and gratuities plus debt service charges will hit 80% of government revenue by 2029, 90% of revenue by 2034 and exceed 100% of revenue by 2038, back-of-the-envelope calculations show.

In short, revenue needs to grow a lot faster and expenses cannot continue growing faster than revenue if Malaysia wants to have greater fiscal flexibility to tackle future challenges, including an ageing population and climate change.

The Malaysian economy and ringgit would probably fare a lot worse if government finances do not benefit from higher commodity prices and the country were not a net oil and gas exporter. Yet, even with stellar exports, the government finds itself needing to go on an austerity drive to help fund the outsized RM80 billion blanket subsidies bill — a sizeable portion of which could have been saved if subsidies had been targeted to only those who need them the most. And this is a year in which the budget benefits from the one-time Cukai Makmur prosperity tax. If the country’s development plans are any indication, policymakers know revenue and expenditure reforms are long overdue.

The Edge’s calculations show that GDP growth alone will not be enough to maintain the country’s debt affordability in the long run if the necessary reforms are not made to raise revenue and keep expenses in check.

It would seem that the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which in its July review cut Malaysia’s 2022 GDP growth projection from 5.6% to 5.1% — below the official guidance of 5.3% to 6.3% — would be among those waiting to see reforms taking place post-pandemic to restore monetary and fiscal flexibility.

“Tighter monetary policy will inevitably have real economic costs, but delay will only exacerbate them. Targeted fiscal support can help cushion the impact [of rising prices] on the most vulnerable, but with government budgets stretched by the pandemic and the need for a disinflationary overall macroeconomic policy stance, such policies will need to be offset by increased taxes or lower government spending. Tighter monetary conditions will also affect financial stability, requiring judicious use of macroprudential tools and making reforms to debt resolution frameworks all the more necessary.

“Policies to address specific impacts on energy and food prices should focus on those most affected without distorting prices. And as the pandemic continues, vaccination rates must rise to guard against future variants. Finally, mitigating climate change continues to require urgent multilateral action to limit emissions and raise investments to hasten the green transition,” IMF said in the July 2022 update of its World Economic Outlook report that trimmed global GDP growth to 3.2%, down 0.4 percentage points from April. IMF also trimmed its forecast GDP growth for Malaysia from 5.5% to 4.7% for 2023.

Apart from high vaccination rates, Malaysia has much to improve on. The country is fortunate to be blessed with natural resources and to have national oil and gas company Petroliam Nasional Bhd (Petronas) to bolster the annual budget, but it can do more to ensure that future generations will continue to benefit from a strong cash cow.

If Malaysia had set aside just RM1 billion a year since 1988, when the National Trust Fund (KWAN) was set up to ensure that future generations could continue to benefit from the country’s natural resources, for instance, and grown it consistently at 5% a year, KWAN would have been a RM90 billion fund today. KWAN would have been a RM80 billion fund in 2020 (with only RM33 billion cumulative contribution and RM47 billion investment gains) instead of just RM19.5 billion (of which RM10.4 billion were contributions from Petronas while RM9.1 billion were generated from investments) when Covid-19 hit.

If RM1 billion had been set aside every year and grown at only 2% a year consistently, some RM33 billion would have been saved and grown to RM46 billion in 2020, when the government asked to withdraw RM5 billion but ended up withdrawing RM6 billion for vaccine and vaccine-related expenses in 2021 (see Graphic 3).

If RM2 billion had been set aside a year and grown the same way, the fund size would have reached RM100 billion (at 2% per year) and RM180 billion (at 5% per year) — larger than the RM159 billion fund size of Kumpulan Wang Persaraan (Diperbadankan) (KWAP), which was set up to eventually help pay part of the government’s civil service retirement obligations.

If it had, Malaysia’s sovereign rating may not have been six notches below the AAA rating of Singapore, which — having squirrelled away a trillion dollars in less than six decades from its separation from Malaysia in 1965 — is facing an entirely different debate of whether more of its reserves should be used for the people today rather than saved for future generations.

When revising its outlook on Malaysia’s sovereign rating to “stable” on June 27, S&P Global Ratings had said it “may raise the ratings on Malaysia if fiscal outcomes outperform our forecast”.

“This would be shown from net debt stock falling below 60% of GDP or interest payment [falling to] less than 10% of general government revenues,” S&P wrote.

This is impossible without a combination of factors, including significant change to Malaysia’s revenue generation capabilities and a reduction in annual overhead spending needs, unless the RM1 trillion debt burden is paid down significantly or its interest cost halves, along with very strong GDP growth.

Singapore’s trillion

Questions in parliament with regard to Malaysia’s reserves last week were answered only with the central bank’s foreign reserve figures, which official figures show stood at US$107 billion as at mid-July, down 8.5%, or US$9.9 billion, from US$116.9 billion as at end-2021.

That is significantly smaller than the US$103.6 billion year-to-date decline in foreign reserves at the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) — which uses currency strength as an inflation hedge. MAS’ foreign reserves stood at US$314.3 billion as at end-June, preliminary figures show, down from US$345.28 billion as at end-May this year and US$417.9 billion as at end-2021. The decline this year is larger if measured from the US$426.63 billion in February, according to data on the central bank’s website.

That said, Singapore is widely believed to have at least S$1 trillion in financial reserves, and the figure is different from MAS’ official foreign reserves.

Thanks to posts circulated on social media in the past fortnight, some people probably believe Singapore’s reserves to be closer to S$1.57 trillion.

That S$1.57 trillion is actually the asset portion of the Singapore government’s balance sheet (as at end-March 2022), which is seen as an indication of the size of the nation’s financial reserves, which is not disclosed for strategic reasons.

The Malaysian government, which has yet to move from cash accounting to accrual accounting, reports its financial statements (differently from Singapore) without an asset portion.

Singapore’s having at least S$1 trillion in reserves is a safe assumption, however, considering the way in which it spends money, that it has zero net debt, the size of assets at state holding company Temasek Holdings Ltd (S$403 billion as at March 2022) and the US$314 billion foreign reserves (preliminary end-June) at MAS, even though the size of funds with Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, GIC Pte Ltd, is not published.

These three entities (Temasek, MAS and GIC) invest and grow Singapore’s reserves, and the portion of profits used is what the city state calls net investment return contribution (NIRC), which bolsters Singapore’s annual budget by about one-fifth every year since 2016, except in 2020, when it was 13%. NIRC of S$15 billion to S$21 billion a year has been more than 3% of its GDP since 2016 and is estimated at 3.8% of GDP this year, official figures show (see Chart 6).

Better spending habits

By spending less than its annual revenue most years, investing its reserves and making sure that at least half of annual profits are reinvested, Singapore was able to fund a bigger budget with Covid-19-related aid and stimulus without taking on debt the way most countries did worldwide (see Chart 7).

Given that the high-income island republic is among countries that did not accumulate sizeable debt during the pandemic, its currency strength should come as no surprise — especially given that its currency strength is used to control inflation. Singapore tightened its monetary policy for the fourth time in nine months in mid-July, the second off-cycle move after an unscheduled tightening in January. Even then, the Singapore dollar is down about 2.2% year to date versus the greenback, which is still going strong.

Meanwhile, in Malaysia, some policymakers are finding themselves having to explain the removal of excess monetary accommodation to certain segments of the population, when the overnight policy rate (OPR) had been raised only 50bps to 2.25% and remains a full percentage point below the 3.25% that it was at before a 25bp cut to 3% in May 2019, where it remained until another 25bps was trimmed in January 2020.

Helped by high crude oil prices as well as stellar crude palm oil (CPO) prices, the ringgit had weakened only 6.5% against the US dollar year to date, compared with 7.7% for the Taiwanese dollar, 9.3% for the won and 7.3% for the baht at the time of writing (see Chart 8).

And with the US federal funds rate raised to 2.5% (upper-bound) after a 75bp hike on July 27, Malaysia’s 2.25% OPR now lies a shade below it for the first time in more than 15 years (see Chart 9).

The OPR is expected to reach at least 2.5% by the last scheduled Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting on Nov 3, if not as early as Sept 8, with the more bullish forecasters expecting 2.75% by year end and 3% by March 2023, Bloomberg data shows (see tables).

There are those who reckon that the MPC will have the chance to make its first-ever 50bp hike in September, especially if the release of 2Q GDP figures in August is stronger than expected. They are not holding their breath, though. The OPR will still reach 3% by March 2023 even if the MPC normalises it by the expected 25bps at each of its next three scheduled meetings.

By November, though, the US federal funds rate is expected to be nearer to 3.5%, with the Federal Open Market Committee slated to meet again in late September, early November and mid-December.

These headwinds mean it would not be easy to rebuild fiscal buffers that had been depleted during the pandemic. What is certain from the numbers, however, is that reforms will be forced upon Malaysia within the coming decade — one way or another. It is better to bite the bullet before reality bites.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.