LAST month, when a woman in Shenzhen, China, put a down payment of RMB120,000 (about RM76,700) for a house in the countryside after selling 20 newly launched iPhone 7s that her 20 boyfriends had bought her, it made headlines around the world.

Whatever they might think of her actions, most Asian consumers would have noticed how prices of Apple phones have climbed in recent years.

When the late Steve Jobs launched the first-generation iPhone in 2007, the retail price was US$399 to US$599, or roughly RM1,321 to RM1,984 with the ringgit at 3.31 to the greenback. The relatively stronger ringgit allowed the average Malaysian to purchase it, even when more than half of the country’s households were earning below RM2,552 a month.

Today, the cheapest iPhone 7 Plus retails at between RM3,500 and RM4,500 — nearly an entire month’s salary for at least 50% of Malaysian households (with median household income at RM4,585 in 2014). The price had been fixed when the ringgit was at 4.2 against the greenback and does not include the 6% Goods and Services Tax.

At such prices, 20 iPhone 7 Plus could raise RM90,000, which is higher than most Malaysians’ annual income.

But what is worth examining is not so much how the Chinese woman managed her “20 mobiles for a house” stunt but the impact of a weaker ringgit on Malaysians’ purchasing power, especially since most currency forecasters do not expect the ringgit to rise above 3.80 to the greenback in the next two years.

Last Friday, the ringgit was trading largely north of 4.40 to the greenback and at least one ringgit forecaster, Barclays, already expects the ringgit to weaken to 5.0 by year-end, Bloomberg data show. Just seven weeks ago, when the same data was extracted, the most bearish forecaster was only looking at the current 4.40 level for this year.

It is worth noting, though, that the most bearish forecaster still expects the ringgit to average 4.70 next year (no change from late-September) but both mean and median expectations have increased by 8 sen to 12 sen for 2017. Forward rates are even more bearish, jumping to 4.47 for 2017 from 4.21 seven weeks ago (see table).

Whether or not sentiment is overly bearish, there is no disputing the fact that foreigners are again pulling funds from emerging markets on renewed prospects of a US interest rate hike as early as next month. Expectations surrounding the potential fiscal spending that the US may undertake under President-elect Donald Trump are also drawing funds away from the region.

While the ringgit was not the only currency that depreciated against the US dollar after Trump’s surprise win on Nov 9, it was among the hardest hit last week, partly owing to confusion in the market after Bank Negara Malaysia on Nov 11 directed locally-licensed banks to ignore offshore ringgit rates when setting their ringgit reference rate and demanded that foreign banks provide written commitment to not trade ringgit non-deliverable forwards.

The latter raised questions about the central bank’s reserve adequacy and sparked concern that Malaysia might impose capital controls as it did in 1998, when it pegged the ringgit at 3.80 to the US dollar to combat currency speculators and protect the local economy. Bank Negara assistant governor Adnan Zaylani Mohamad Zahid told reporters on Nov 18 that concerns over capital controls were misplaced because such a “risky” move could hurt Malaysia. He also said reserves remain at “comfortable” levels and that the ringgit, being a non-internationalised currency, is “one protection that would already prevent the kind of destabilising forex market” witnessed in 1998. (See sidebar on ringgit speculation).

Even so, Malaysia faces “monetary policy challenges with a weaker currency” as the large capital inflows into the country between late-2009 and early 2013 began to reverse when the US Federal Reserve first spoke of normalising interest rates. “Higher reserves levels would provide a buffer against rising volatility” amid an uncertain global environment and weakened export demand, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) said in an economic assessment report on Malaysia released this month.

While Malaysia is performing strongly relative to other middle-income countries in terms of employment, access to healthcare and provision of basic services such as drinking water and electricity, the OECD found that it is performing relatively poorly in “education outcomes, healthcare costs, women and elderly labour force participation, pollution and social welfare”.

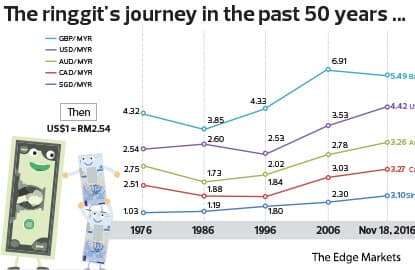

A weaker ringgit would make imported Western medicine more expensive and reduce the number of Malaysians who can afford to seek tertiary education outside Malaysia. A back-of-the-envelope calculation shows that the cost of a four-year undergraduate course in Australia today for a 19-year-old Gen Y can easily be double that of a Gen X who went to university in 1986 — due to today’s higher cost of living and the exchange rate (1.73 against the Australian dollar in 1986 vs 3.29 today). The situation is similar for those looking to study in Singapore, Canada, the US or the UK, where universities are ranked higher than Malaysia’s public universities.

The OECD report also found that high-skilled job creation “has not kept pace with tertiary education rates” in Malaysia, “contributing to outflow of skilled labour abroad”.

The Singapore dollar’s strength against the ringgit, for instance, is one reason why Malaysians who studied in Singapore and are working there are finding it hard to return to Malaysia, where they would face higher personal income tax. In 1976, one needed RM1.03 to buy a Singapore dollar. A decade later, one needed RM1.80. In 1997, it was RM2.30. Today, it is RM3.10.

“The divergence in the value of the ringgit versus the Singapore dollar can be explained by the higher income and productivity levels in Singapore. It has been able to move up the value chain, producing higher-value goods and services that are skills and knowledge-intensive, leading to a high-income, high-wage economy as well as a strong currency that reflects its international purchasing power,” says Dr Yeah Kim Leng, economics professor at Sunway University Business School and former group chief economist at credit rating agency, RAM Holdings Bhd.

According to the OECD report, Malaysia needs labour market reforms that “raise returns to work, increase participation rates and facilitate the transformation to high-skilled and high-productivity activities” that the country requires to become a high-income developed nation.

Here, a stable and strong currency is a factor that “tends to inspire confidence” and necessary to attract foreign direct investments as well as investments by local manufacturers to move up the value chain, says RHB Research Institute executive chairman and chief economist Lim Chee Sing.

“As competition intensifies, particularly from lower-cost producers, Malaysia can’t rely on a cheap currency to boost exports and economic growth. The way forward is to innovate and increase productivity to move up the value chain, and that needs a stable-to-stronger currency to inspire confidence to entice investors to take a long-term horizon to invest and progress up the value chain,” he says.

Moreover, not all local exporters enjoy the “very short-term” benefit of a weaker ringgit. “For manufacturers relying on imported inputs, the uncertain direction of a currency very often creates fears of product mispricing and could cause them to hold back production and investment, albeit temporarily,” Lim says, adding that investments in product quality, branding strength that commands recurring demand, good service and reliable marketing network are necessary to remain competitive over the long haul.

Julia Goh, economist at UOB Bank Malaysia, has a similar observation: “Businesses find it hard to manage when currencies continue to fluctuate rapidly. I think we are at the point in our economic cycle of promoting more investment and higher value-added activities, which will see higher dependence on imports. As such, the weaker currency does not help.”

“The strength of a currency reflects not only the country’s economic fundamentals — such as income, productivity, growth, inflation and current account balance — but also ‘soft factors’ that influence investor confidence and market sentiments, such as the quality of institutions, macroeconomic management capabilities and soundness of policies,” Yeah adds.

To be sure, currencies can be misaligned by short-term sentiment and confidence issues but should reflect an economy’s fundamentals in the long run.

Yet, more than a year after the ringgit skidded past the 3.80 peg to the US dollar between September 1998 and July 2005, economists and the central banker still see potential volatility ahead. Some already see 4.0 to the greenback as “a new normal”.

What is certain is that no one expects the ringgit to strengthen to pre-1997/98 Asian financial crisis levels through to 2020. If Malaysians need to live with a weak ringgit for the foreseeable future, policymakers need to act quickly and come up with smarter ways to ensure Malaysia makes the most of its available resources. The more overdue reforms are deferred, the harder it would be to retain the talent pool required to move up the value chain.

A weak ringgit also makes it harder for local companies and institutions to seek growth and investment returns outside Malaysia.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.