This article first appeared in Forum, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on December 7, 2020 - December 13, 2020

“You become addicted to the moon and it’s not always possible to come back down.” — Diego Maradona

It was no idle boast: no footballer has been hailed as coming “from another planet” as often as the Argentine genius. He had plenty of earthly addictions, too, but when it came to the beautiful game, he occupied a uniquely rarefied zone.

National hero, favourite son and soul brother of Evita and Che Guevara, he had a status in his homeland that a pervasive dark side only enhanced. After all, it was his devilry that delivered the Hand of God.

Besides being arguably the greatest player of all time, he was a living contradiction: a diminutive colossus who could enrage and enrapture in the same body swerve; a superstar who remained a low life, took his teams to the heavens but never left the slum.

His fitness trainer Fernando Signorini tried to explain it: “Diego and Maradona are two different people. Maradona was the character the boy Diego had to come up with to face the demands of the football business and the media.” But it was difficult to distinguish between the two.

His countrymen never did and his sudden and unexpected loss at 60 is something they are struggling to come to terms with. More than a week since he was buried, Argentina is still crying.

Divine powers were bestowed upon him in childhood when he first discovered a holy communion with the ball. And, in later life, a fondness for a prank and an ability to dodge death as he did tackles led some to think it was all an elaborate hoax. You wouldn’t have put it past him.

It is hard to talk about finality when it comes to Maradona. Lionel Messi spoke for millions when he claimed “he’s eternal”, which is why cremation was not an option. And had his ashes been scattered on any ground in the world, the entire pitch would have been dug up before nightfall.

By any standards, the global outpouring of emotion that his passing triggered has been extraordinary — even for someone once considered to be “the most famous man in the world”. Indeed, you wouldn’t be surprised to hear that his legendary left foot has been preserved for posterity — alongside Einstein’s brain.

Few founders of nations or religious deities have evoked such grief, adulation and forgiveness. And with Maradona, there was a lot to forgive. Drugs, dodging tests, taxes and paternity suits, as well as consorting with the mafia, were merely the headline acts.

Apologists point to his upbringing. The fifth of eight children, he was raised in a two-room shack with no running water. He quit school at 13 but had absorbed the lessons to survive the barrio. Three years later, he was in the national team, but it would be anything but a rags-to-riches story.

Perhaps the most perplexing of many paradoxes is that he died poor. Italy’s Corriere della Sera claims he had only £75,000 in his bank account while a fleet of cars and two properties may not raise enough to pay the £33 million still owed to the Italian taxman.

For a World Cup winner and sporting icon, it’s a staggeringly small reward even after a life of excess. His counterparts today, Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo, are well on their sure-footed way to becoming billionaires.

He played before salaries went through the stratosphere and was far too generous and distracted. And his “brand”, far too toxic. His entire life was lived in the public gaze. Ball juggling as a toddler, marriage, divorce, bust-ups and paternity denials were all essential viewing for an adulatory nation. But adulation alone didn’t pay the bills.

In later years, he earned big bucks as a coach in the Gulf, Belarus and Mexico, but they, too, were squandered and siphoned off. He had huge entourages and went on epic binges. In 2005, he had ballooned to 120kg and had to have his stomach stapled. He lost 50kg but not his appetite for life.

His peak as a club player came in Naples where he couldn’t refuse the Neapolitan mafia’s offers of largesse, and cocaine, hookers, pizza and champagne would eventually take their toll.

But not before he’d inspired Napoli to the only two league titles in their history, the Coppa Italia and the UEFA Cup. His kinship with Italy’s poorest city saw a wall at the main cemetery adorned with a mural of him along with a message to the dead, informing them: “This is what you’ve missed.” The next day someone wrote: “How do you know we’ve missed it?”

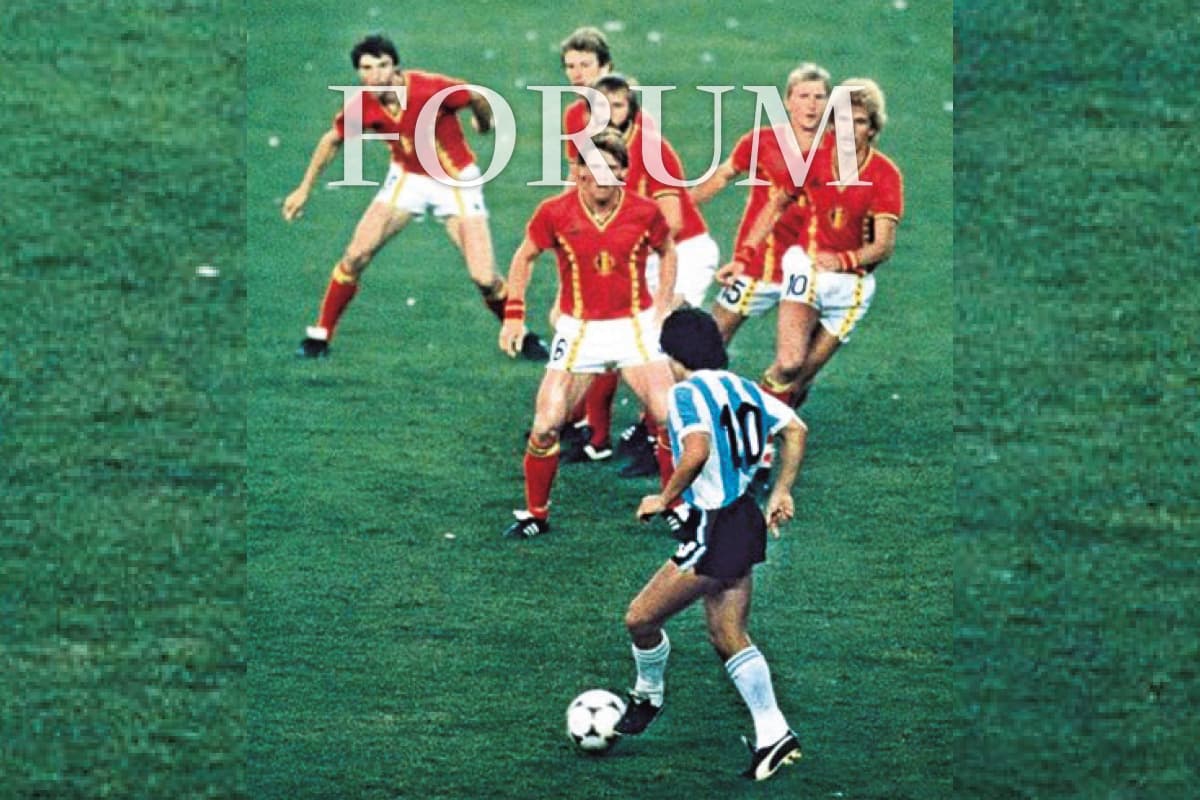

His peers were also in awe of him. When Michel Platini saw Zinedine Zidane showing off his keepy-uppy skills, he shrugged: “Maradona can do that with an orange.” And England’s Gary Lineker admitted that after witnessing his wonder goal in the 1986 World Cup, he had to stop himself from applauding.

Typically, Maradona confessed that he sometimes preferred the handled goal, quipping: “It was like stealing the wallet of the English.” But it meant an awful lot more to his countrymen than petty larceny.

Only Maradona could claim a narrow football victory had avenged a humiliating military defeat, but he knew his people. Four years earlier, Argentina had invaded the Falkland Islands, and, according to Maradona, “lost 20-0”. His two goals brought a 2-1 win over England. National pride was restored even though the Falklands remain British.

Four years later, in a World Cup semi-final against Italy in Naples, of all places, only Maradona would have had the audacity to ask Italian fans to cheer against their own team — and live to tell the tale. Most didn’t but the ultras did and Argentina won through.

He transcended the sport like no other footballer. Neither the immortal Brazilian Pele nor his own “successor” and compatriot, Messi — the only two fit to share the podium — come anywhere near. The only other sportsman with a similar global constituency was Muhammad Ali, another rebel with a cause and the common touch.

With Maradona, there was no public relations man; no one edited his statements, often made under the influence of alcohol and drugs. In an increasingly homogenised, sanitised world, he was the real, achingly human and unexpurgated deal.

With an image of Che Guevara tattooed on his leg, he befriended left-wing dictators Fidel Castro of Cuba and Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez and spouted populist themes. But he was seldom coherent enough to speak as well as he could play.

Still, for all his peccadilloes, he was a man of the people, which neither Pele nor Messi are. Both have had the sense to manage their lives in orderly fashion but are seen as goody-two-shoes in comparison. Ronaldo? A touch too much hair gel.

Proof, if it were needed, that we humans are tired of the manicured images and media-trained monotones we hear and like a bit of devil in our heroes, especially those who bare their souls to the world.

He was a wonderful footballer, a World Cup winner, a hopeless businessman and a serial sinner, but that is more than enough for him to become Argentina’s patron saint. And probably football’s too.

Bob Holmes is a long-time sports writer specialising in football

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.