This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 6, 2023 - March 12, 2023

IN 2014, former prime minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak requested a quick chat with the fund manager of Bridge Funds, which was managing 1Malaysia Development Bhd’s (1MDB) purported overseas investment of US$2.3 billion.

This was an unusual request as Najib had left the inner workings of 1MDB mostly to fugitive financier Low Taek Jho (Jho Low), who put himself forward as the former premier’s proxy and adviser to the company.

The Ministry of Finance (MoF) — Najib was the minister at the time — had hand-picked Bridge Partners Investment Management (Cayman) to handle the US$2.3 billion, based on “the stability of the firm, its reputation [and] its track record in investments”.

Kevin Michael Swampillai, a 58-year-old Malaysian who was previously BSI Bank Singapore’s head of wealth management services, testified that in 2014, his colleague, BSI Singapore relationship manager Yak Yew Chee, had told him and his subordinate Yeo Jiawei that Najib wanted to have a quick chat with the fund manager of Bridge Funds, represented by Lobo Lee.

Testifying as a prosecution witness at Najib’s 1MDB-Tanore trial, he said the US$2.3 billion investment in Bridge Funds by 1MDB’s Cayman Islands subsidiary Brazen Sky Ltd was in fact a sham.

Kevin said he could not remember when in 2014 the request was made, but members of parliament began asking questions about Bridge Partners, given that not much was known about the fund managers.

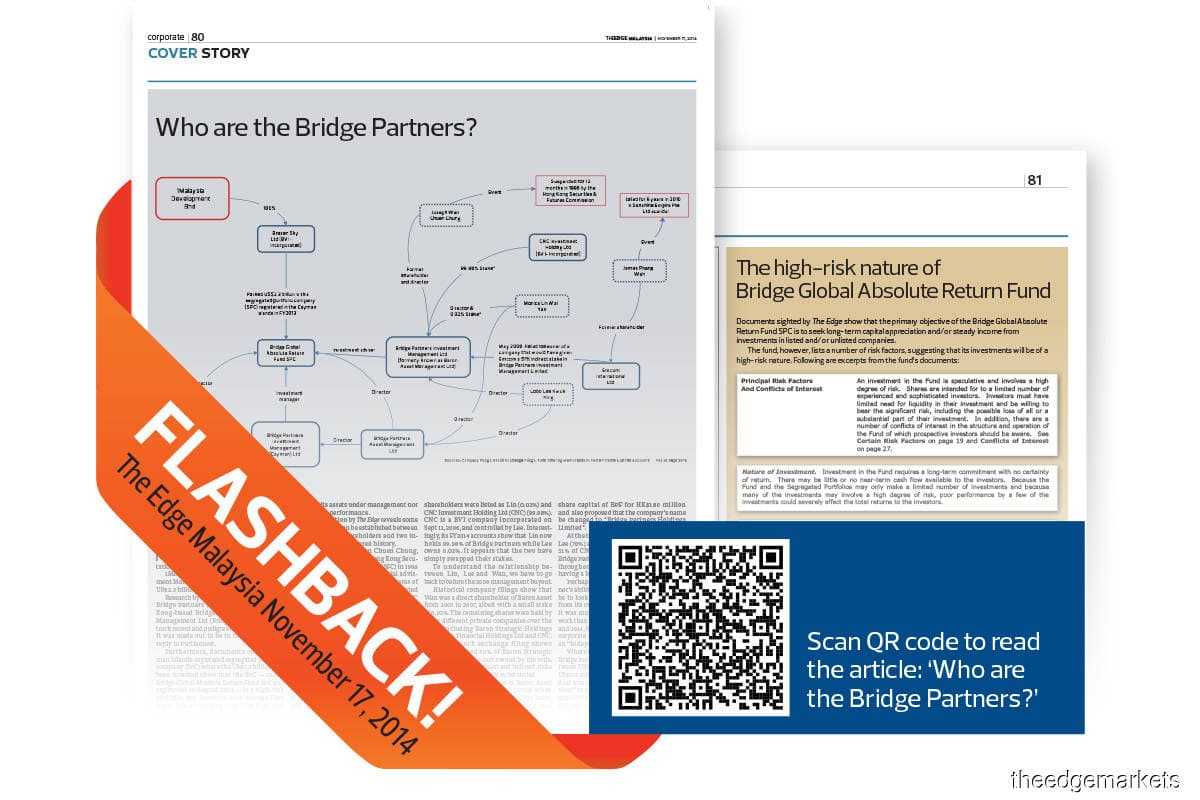

In November 2014, The Edge had also published a special report titled “Who are the Bridge Partners?”, which delved into the inner workings of Bridge Partners and provided a clearer picture of who Lee is (scan QR code at top right).

The article showed that Bridge Partners (Cayman) was part of Hong Kong-based Bridge Partners Investment Management Ltd (Bridge Partners), whose track record and pedigree were not exactly what they were made out to be in the written MoF reply to parliament.

Furthermore, documents on the Cayman Islands-registered segregated portfolio company (SPC), where the US$2.3 billion had been invested, showed the SPC — called Bridge Global Absolute Return Fund SPC and registered in August 2012 — to be a high-risk portfolio, with investors being warned they could lose everything.

The documents also showed that Bridge Partners (Cayman) was appointed the investment manager via a tripartite agreement signed between itself, Bridge Global Absolute Return Fund and Brazen Sky — a British Virgin Islands (BVI) registered company owned by 1MDB.

Information on the Hong Kong-based Bridge Partners was limited as, unlike established global fund managers, it did not publish figures on its assets under management nor its investing performance.

Following Najib’s request, Kevin said a conference call was then arranged with Yeo and Yak with the fund manager’s representative Lee.

“The call connection was bad as Najib was calling from somewhere overseas and Lee was on a ferry to Macau. There was constant static interference during the call so both parties did not hear each other too well,” he said.

On the stand, Kevin explained that Brazen Sky maintained an account with BSI that was opened in 2012, ostensibly for the purpose of transferring the ownership of certain drilling assets held under the 1MDB-PetroSaudi joint venture to the Bridge Partners fiduciary fund.

He testified that the Brazen Sky transaction through Bridge was a different fiduciary fund transaction “in both form and substance compared” to the transactions by SRC International Sdn Bhd, 1MDB Global Investment Ltd and Aabar Investments PJS.

Highlighting some of the differences, Kevin said there was no cash involved. This was because “the intention was to transfer the ownership of certain assets from the PetroSaudi JV to Bridge at what turned out to be a vastly overinflated valuation”.

Elaborating further, he said the promissory notes involving Bridge funds were used as IOUs that were exchanged between Brazen Sky and Bridge to satisfy consideration for the transfer of the PetroSaudi assets to Bridge, and the issue of shares in the Bridge funds to Brazen Sky.

He added that the key parties in this transaction were Yeo and himself acting on behalf of BSI, Lee acting on behalf of Bridge, and Jasmine Loo and Terence Geh on behalf of 1MDB.

Using fiduciary funds to launder 1MDB money

During his testimony last week, Kevin elaborated on how Jho Low used fiduciary funds to essentially move billions in 1MDB money around while giving the optical illusion to stakeholders that the funds from 1MDB were in real investments.

Reading from his witness statement before Justice Datuk Collin Lawrence Sequerah, Kevin testified that at the beginning of the client relationship with Jho Low and SRC, 1MDB and Aabar in 2011, he was not aware of Jho Low’s motives for selecting fiduciary funds over other solutions such as insurance structures and trusts.

“However with the benefit of hindsight based on the information that has come out in the public domain since 2015, it is evident to me that Jho Low intended that the fiduciary funds would be better at giving the optical illusion to various stakeholders in Malaysia and elsewhere that the funds belonging to SRC, 1MDB and Aabar were invested in bona fide investment instruments such as investment funds,” he said.

Kevin detailed how Jho Low came to use the fiduciary funds by companies such 1MDB Global Investments Ltd, SRC, Brazen Sky and Aabar, which can be traced back to a meeting he had with Jho Low in 2011.

“I understand Jho Low had come to know about fiduciary funds and how they are used from his relationship manager Yak.

“Yak then asked me to conduct a presentation to Jho Low in order to explain to him the entire range of fiduciary solutions available through BSI Bank. This range of solutions included trusts, insurance structures as well as fiduciary funds,” he said.

Kevin added that clients using fiduciary funds have virtually limitless flexibility to decide on the structure of transactions placed through fiduciary funds. For example, they can choose the target destinations where the money will eventually end up.

They decide on the instruments (such as equity shares or loans in the form of lending agreements such as promissory notes) used to optically legalise the flow of money from the fund to target companies or assets intended to be acquired. The clients are also in control of the timing and amounts channelled through such fiduciary structures.

He testified that not long after this meeting, the SRC account was opened, followed by Aabar Investment PJS Ltd and Brazen Sky in 2012 and 1MDB GIL in 2013.

“The use of fiduciary funds was prevalent in all of these accounts without exception. The common denominator prevalent in all these accounts or companies was the presence of Jho Low and the fact that all these companies came under the auspices of the Ministry of Finance Malaysia,” he said.

Kevin then testified that after using this modus operandi, Jho Low had also used the fiduciary funds method for his other shell companies such as Cistenique Investment Fund, Enterprise Emerging Market Fund (EEMF), Devonshire Capital Growth Fund and Bridge Absolute Return Fund.

“Each of these funds were domiciled in offshore fund jurisdictions which are widely considered to be ‘light’ in terms of regulatory oversight and control,” he said of the funds that were either domiciled in Curaçao in the Caribbean or in BVI and Cayman Islands.

“Each of these funds was managed and administered by third-party fund managers but in all transactions undertaken by Aabar BVI, 1MDB, SRC in these funds, the investments and structure thereof was determined by the client,” he said.

In the case of the fiduciary funds used by Aabar, SRC and 1MDB, he added, the monies transferred to these funds were not placed on fiduciary deposit. “[...] rather they were conduits to channel monies to various beneficiaries known only to the clients themselves while at the same time obscuring the intentions of the client from scrutiny by various stakeholders in Malaysia.”

Withholding information from KPMG

In 2012, 1MDB faced an impending audit by KPMG, and its executive director of finance Terence Geh Cho Heng did not want the auditors to know the true nature of the underlying assets in the Bridge Funds.

“BSI Bank had no obligation to disclose any information to the client’s auditors unless expressly authorised by the client. In the case of Brazen Sky, I was directed by Terence Geh not to disclose any information about the underlying assets in Bridge Funds,” Kevin said.

Earlier, the BSI banker testified on March 16, 2022, in the New York trial of ex-Goldman Sachs banker Roger Ng, where he said Geh told him KPMG would be asking about the account that was supposed to hold liquid assets valued at US$2.3 billion. Geh instructed him not to reveal to the auditor that the only assets were two illiquid drilling ships.

The US$2.3 billion that was parked in a Cayman-registered fund was a point of contention that 1MDB had with its auditors, and when KPMG refused to sign the FY2013 accounts unless it was provided with more proof of the nature and value of the Cayman fund plus a few others, the auditors were sacked on the instruction of Najib and replaced with Deloitte.

Kevin and a few other BSI bankers — Yak, Yeo and Yvonne Seah — received kickbacks from the various 1MDB transactions. Kevin was subsequently banned from working in the financial sector in Singapore while Yak, Yeo and Seah were jailed 18 weeks, 30 months and two weeks respectively.

Swiss-based BSI was ordered to shut its operations in Singapore.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.