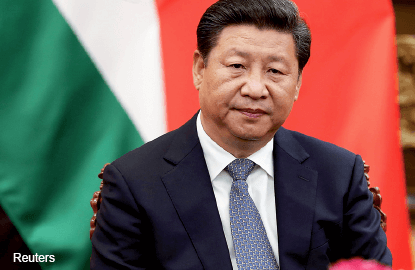

TALK about mixed signals. Last week, Chinese leader Xi Jinping announced a 300,000-man reduction in the size of the People’s Liberation Army — a decision at least partly calculated to look like China has no aggressive intentions toward the rest of the world.

Yet at almost the same time, he sent five Chinese ships into the Bering Sea near Alaska, in an unprecedented manoeuvre timed to coincide with the last day of President Barack Obama’s visit to the state. This sort of symbolism is pretty close to the textbook definition of muscle-flexing aggression.

So what’s going on? Is Xi being peaceful or being hostile? The answer is complicated — but so are the circumstances of the cool war between China and the United States.

Domestically, Xi wants to signal that he has control over the military, that reforms are needed and under way, and that China won’t waste money on a land force that has little to do with its strategic position. Although these moves aren’t exactly pacifist, at least they aren’t warmongering.

Simultaneously, Xi wants to signal to both his domestic and his foreign audiences that China will continue to press for a global strategic advantage against the US by focusing its military efforts where the US hasn’t asserted its own power.

The Arctic turns out to be a great example. The US Navy isn’t a visible presence in the Arctic, and the Coast Guard’s showing there isn’t much more significant.

In advance of his state visit to Washington later this month, Xi must’ve intended to signal to Obama that he will aggressively pursue China’s interests where and when the US hasn’t staked its claim.

It will be difficult for Obama to raise the issue of the five-ship convoy with Xi, because Xi can say that China wasn’t treading on any US waters.

This pre-summit gamesmanship has an added benefit for Xi. It shows his senior military brass that the troop reduction isn’t truly a back-pedalling from the pursuit of Chinese national greatness. It’s been widely noted that Xi has closer ties to the military than either of his predecessors as China’s president.

What does this delicate two-step mean for the future of China-US relations? It poses in miniature the profound dilemma that confronts US policymakers today, and will confront the next president.

China’s economic rise has driven a steady but in many ways cautious expansion of its military capacities. Its military budget has risen at roughly 10% a year according to official estimates, and perhaps more.

China’s well-documented provocations in the seas around it have caused grave concern to its neighbours, almost all of whom rely on bilateral security relationships with the US.

The aggressive US response would be to embrace openly a strategy of containing China. This would mean strengthening those bilateral relationships and perhaps increasing country-to-country military ties within Asia where possible.

Advocates of this containment strategy could, and no doubt will, point to the Arctic episode as an instance of where some meaningful response is called for — namely strengthening the US presence in the Arctic.

The more moderate, even dovish US response to China’s slowly changing military posture would be to refuse to take the bait, maintaining existing security relations without raising the stakes by devoting greater military resources to the Pacific.

Doves argue, with some reason, that responding to China with overt containment would just alienate the Chinese public, strengthened hardliners within the army, and commence an irrational, costly and potentially very harmful cycle of mutual escalation.

There’s a reason the US hasn’t focused forces in the Arctic. The US interest there is in free trade and shipping. So far, no one, including Russia, has done anything to impede that interest.

In the unlikely event of some Arctic move by Russia or even China, the US could exploit its vast naval superiority and send its aircraft carriers and destroyers north.

Over the last six and a half years, the Obama administration has mostly pursued a moderate version of the dovish strategy vis-à-vis China. US officials don’t say the word “containment” and China in the same sentence, or even the same paragraph, lest they give offence and create counterproductive consequences.

Obama famously announced a pivot to Asia, but in practice that has primarily meant a reduced military presence in the Middle East rather than a substantially increased naval presence in the Pacific.

The administration has encouraged allies like Japan’s Shinzo Abe in their own efforts to harden their defences and stand on their own feet. That’s a kind of containment. But it’s also a kind of recognition of Asian allies’ fears that the US might not always be there to protect them from China.

Obama’s approach to China has been broadly consistent with his general foreign policy, which recognises the limits of US influence in contexts where the exercise of military power is unlikely because of situational constraints.

It’s probable, however, that this approach will change to some degree in the next administration, whether the president is a Democrat or a Republican. And that’s probably a good thing.

China’s response to Obama’s moderation has been continued cautious expansion. Greater resistance on the US side would put pressure on China not to take advantage of the US in places where it recently hasn’t been necessary to project force.

In the long run, this would save effort and reduce the dangers of confrontation, not raise them. There are risks associated with containment. But the risks associated with non-containment are greater. — Bloomberg View

This article first appeared in digitaledge Daily, on September 14, 2015.