This article first appeared in Personal Wealth, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on September 23, 2019 - September 29, 2019

The US holds a potentially decisive upper hand should the trade war continue to escalate. Quite simply, its semiconductor industry and technological capabilities remain vastly superior to anything that currently comes out of China, according to Jonathan Curtis, vice-president of the Franklin Equity Group at Franklin Templeton Investments.

In fact, he contends, Chinese equipment and device manufacturers are still heavily reliant on US-made semiconductor components and technology and will not be able to replace the US semiconductor content in their infrastructure anytime soon.

“Huawei Technologies Co Ltd and the Chinese government in particular are trying to build up the country’s semiconductor space as quickly as possible. But even so, they are many years away from being completely independent of the US semiconductor industry,” says Curtis.

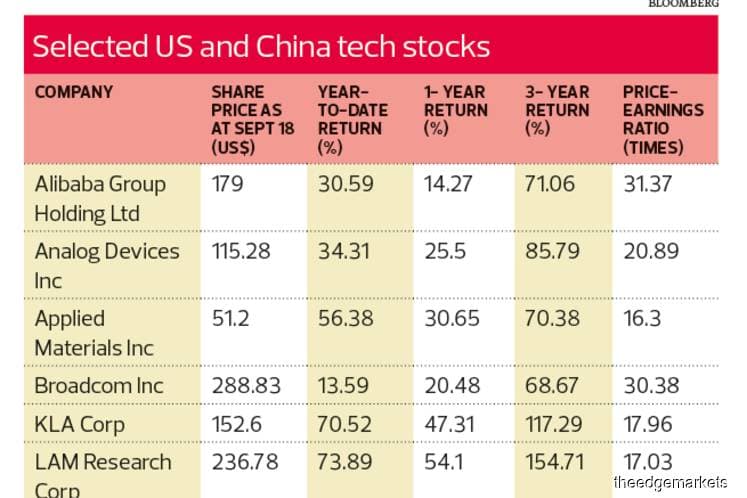

“Therefore, US semiconductor companies are very powerful control points. Ultimately, Huawei cannot build its communications infrastructure without access to many of the components and technologies supplied by companies like Analog Devices Inc, Texas Instruments Inc or Broadcom Inc.

“Sure, China will be able to knock off some circuits and make progress. But they still need US companies such as KLA Corp, Applied Materials Inc and LAM Research Corp. These are the companies that build the equipment and components that ultimately go into finished semiconductors.”

Devices, equipment a risky play

More broadly, the device and telecommunications equipment space that Huawei occupies is one that Curtis’ Franklin Technology Fund is very much underweight on. That is because, trade war fears notwithstanding, he believes that the space is on the wane, particularly as more enterprises wake up to the need to move away from hardware-based devices to software-driven solutions and processes.

Huawei and its public-listed rival ZTE Corp are just two of a wider group of companies that are heavily entrenched in the equipment and device manufacturing space. Its competitors include Nokia Oyj and Ericsson AB.

One-time stock market darlings with massive market shares in the mobile phone market, Nokia and Ericsson began to fall away in the mid-2000s as they failed to keep up with the rise of smartphones. Over the last few years, both have attempted to reinvent themselves, primarily as manufacturers and suppliers of telecommunications network equipment. They have also attempted to position themselves as leaders in the race for 5G proliferation, alongside Huawei.

“We do think that enterprises are slowing down their refreshes of PCs, mobile phones and physical server infrastructure. Businesses and people are pushing more and more of their data onto the public cloud. As such, companies that still manufacture these physical devices will not be particularly differentiated in the future,” says Curtis.

It is important to qualify, however, that Huawei does have the ability to be aggressive with its pricing and secure more market share, at least when compared with the likes of Nokia and Ericsson.

There are several reasons Huawei has done so well, says Curtis. The company has lower cost engineers and the Chinese government regularly finances infrastructure builds throughout the world. These factors have driven the kind of scale that the company has been able to achieve.

In the near term, however, much of the risk in this sector is political and it is particularly susceptible to trade war tensions, says Curtis. “The US and other governments are concerned about China dominating this space. Operating someone’s communications network gives you a powerful vantage point and the US government has made it clear that it does not want to be operating on a planet where all the underlying communications infrastructure is from Huawei.

“The US government knows how easy it is for these networks be infiltrated and used as observation points. It is a national security concern.”

In 2012, the bipartisan US House Intelligence Committee issued a report that accused Huawei and ZTE of being affiliated with the Chinese government, as well as having stolen intellectual property from US companies. Huawei senior vice-president Charles Ding, who was present at the hearing, strongly denied the charge that the company would grant the Chinese government access to its networks.

In May, Huawei was placed on a watch list that requires US firms to seek government approval before selling to this company. However, the Trump administration has since announced a series of policy relaxations.

Although Huawei will remain on the watch list, US Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross said in early July that the US government would issue licences to firms that want to continue selling products to the Chinese company, as long as the products are not perceived as being a threat to national security.

A similar tactic was previously employed to devastating effect on ZTE. In April last year, the US government banned the company from purchasing components from US firms, ostensibly for violating its business laws. Such was the company’s dependence on the US supply chain that its operations ground to a halt for the roughly two months it was prevented from doing business with US entities. The ban was lifted in July last year, but only after ZTE agreed to pay a US$1.2 billion fine.

Seemingly anticipating the crippling effects of the ban, Huawei recently invested in two Chinese semiconductor firms as it sought technology independence in the wake of US sanctions. The company also announced the release of its own operating system, HarmonyOS.

An open-source operating system, it will be installed on all new Huawei devices. The company made the announcement in response to Google’s parent Alphabet Inc complying with the US order to no longer supply technology to Huawei. As a result, Google pulled its Android operating system from all future Huawei devices.

The future is software

More broadly, Curtis is bullish about the accelerating digital transformation that is taking place throughout large portions of the global economy, a theme that is being driven by regular consumers and enterprises alike. He suggests that investors consider companies that service these markets.

This particular investment theme is less prone to trade war concerns as the overlaps with the politically sensitive telecommunications space is fairly minimal. In this regard, there are a number of compelling investments, even in China.

“The Chinese have their own internet and network companies, all of which have access to open-source software. The likes of Alibaba Group Holding Ltd and Tencent Holdings Ltd have never been particularly reliant on US tech companies for what they sell on their platforms,” says Curtis.

“Now, there is some risk that the trade war will slow consumption in China and hence, aggregate demand on these platforms will take a hit. But even so, Alibaba just reported a very strong quarter. So, I believe that these fears are just noise.”

The New York-listed e-commerce and technology giant comfortably beat estimates to post a revenue growth of 42% in its first quarter ended June 30. The company achieved revenue of US$16.7 billion, driven by an increase in annual active customers in its China business. Net income attributable to ordinary shareholders jumped 145% to US$3.1 billion.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.