Thanks to the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax, everyone is now a taxpayer. Here’s a snapshot of how our tax money has been spent in recent years.

The numbers: The share of the operating expenditure (opex) of the budget rose to 99% of government revenue in 2013 and 2014, significantly higher than the 79% to 82% from 1998 to 2003 (excluding 91% in 2000). Opex has stayed above 95% of government revenue since 2008, during which there were two election years (2008 under Tun Abdullah Ahmad Badawi and 2013 under Datuk Seri Najib Razak).

What that means: High opex means more money is going to government operations, leaving less for development expenditure (devex). This is akin to a company having less money to grow the business as most of its income is going to administrative expenses. The saving grace is that the RM50 billion devex projected for 2016 is up from RM47.4 billion in 2015 and RM39.5 billion in 2014, although most of it had to be debt-funded due to the high opex.

The numbers: Based on the total government debt of RM655.75 billion as at 2Q2016, Malaysia’s 2016 debt servicing cost is RM26.64 billion — that is RM2.22 billion a month, RM512.3 million a week or RM73 million a day — enough to give RM828 to every Malaysian (RM2.30 a day to 31.8 million citizens for the whole year).

Debt service charges have increased in tandem with rising debt. While the federal government’s debt remains below 55% of gross domestic product (helped by some off-balance sheet transfers), the absolute amount quadrupled in 15 years to RM655.75 billion in 2Q2016 (excluding RM178 billion in quasi-government debt in 1Q2016) from RM165 billion in 2002. In 2008, debt stood at RM306 billion.

Malaysia only saw budget surpluses between 1993 and 1997 when the economy grew 9.5% per annum on average. This year’s GDP is projected to slow to 4% to 4.5% from 5% in 2015 and 6% in 2014. If a balanced budget is only attained in 2020, Malaysia would have had 23 straight years of budget deficits. Budget 2017 is expected to be the 19th straight year, with the fiscal deficit target expected to be 3%.

What that means: While borrowings are usually needed to fund development, debt service charges are generally seen as unproductive. And nearly 12% of government revenue is needed for this purpose this year with debt service charges at RM26.6 billion — enough to buy Telekom Malaysia Bhd, whose market capitalisation is only RM25.1 billion currently and pays dividend of at least RM700 million annually.

The RM26.6 billion is also enough to give every Malaysian a KFC Dinner Plate meal (RM14.90 each) every week for the whole year with RM50 to spare.

If debt and debt service charges were lower, more money could also go towards helping the middle and lower-income groups. Tellingly, BR1M allocations for the five years from 2012 to 2016 totalled RM20.6 billion (allocation had risen to RM5.9 billion for 2016 from RM1.8 billion in 2012).

Petronas has contributed some RM900 billion in oil revenue (including dividend plus taxes) to the federal and state governments in the past four decades. If 15% of that had been set aside, the country would have at least RM135 billion to cushion the tough economic times.

The numbers: Some 40% of government revenue goes to paying the emolument and pension bill. The nation’s pension obligation of RM19.5 billion in 2016 alone is 8.6% of federal government revenue and 9.1% of opex. A decade ago, pension or retirement costs were only RM8.3 billion. It was even lower in 1997 at RM3.6 billion.

Pension obligation will only rise as Malaysians are living longer and healthcare costs for the elderly will also go up. By 2035, one in 10 Malaysians will be aged 65 and above. By 2021, Malaysia will reach that 7% threshold that the World Bank defines as an ageing society — not that far away.

The civil service emolument bill, on its own, too has doubled the past decade, from RM32.6 billion in 2007 to RM70.5 billion in 2016.

What that means: While it is good that employees get a bigger share of the profits of a company, in an environment of slowing economic growth globally, the odds are stacked against the government’s coffers, although it may well want to continue shouldering the rising civil service emolument and pension bill. That means a civil service and public pension reform would have to be on the cards in the medium term, unless Malaysia can successfully expand its coffers.

The numbers: Malaysia has clearly not skimped on education with RM436 billion allocated to it the past decade (2007 to 2016) — the need here is to get the desired quality from the money spent.

Over the same period, however, the country spent RM221 billion on home security and defence — more than the amount spent on healthcare (RM160 billion) and housing (RM12 billion) put together.

While defence allocation was reduced from RM27.1 billion in 2015 to RM26.9 billion in 2016, it is still nearly double the RM16 billion allocated in 2007 and RM6 billion in 1998.

Healthcare allocation was RM21.7 billion in 2016, almost unchanged year on year, but had more than doubled over the past decade from RM9.8 billion in 2007.

What that means: Malaysia is said to be subsidising more than 90% of healthcare costs, but as Malaysians live longer, there is added pressure on public healthcare funding. Adding to that is the prevalence of diseases such as diabetes, hypertension and cancer, which also adds to the cost of subsidising healthcare. Experts expect a public healthcare reform to take place in the medium term to shift more cost to the consumer.

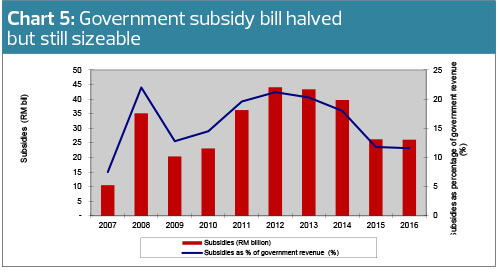

The numbers: Malaysia has cut subsidies for sugar, cooking oil, gas (for cooking) and petrol. The subsidy rationalisation to favour targeted subsidies rather than blanket ones, successfully reduced its subsidies bill. Before fuel subsidies were scraped on Dec 1, 2014, subsidies had reached RM44.1 billion in 2012, RM43.4 billion in 2013 and RM39.7 billion in 2014 — 20% to 21% of total government revenue.

The projection of RM26.1 billion for 2016 (11.6% of government revenue) is just above the RM23.1 billion in 2010 and is still more than double the RM10.5 billion in 2007.

What that means: Subsidies continue to take up just over one-tenth of government revenue. That is not necessarily bad if the money indeed benefits the bottom 40% of the population who need the aid the most. Experts have observed that the government could better stretch every ringgit used for targeted subsidies if resources to help a particular group are pooled, thus minimising agencies’ areas of overlap.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.