This article first appeared in Personal Wealth, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on April 24, 2017 - April 30, 2017

Malaysians often have to rely on word of mouth or go through the arduous task of contacting multiple law firms to get legal services that fit their budget. But even if they manage to find a lawyer, he may not be the right one to take on their case.

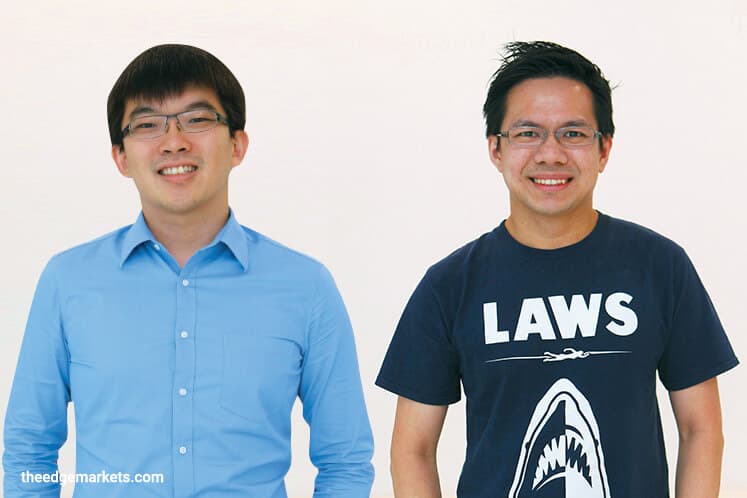

To address this issue, Loo Soon Yi set up CanLaw Asia Sdn Bhd in February. The lawyer discovery service aims to make finding legal services a lot easier. This includes allowing users to compare the fees and services of law firms on its platform free of charge.

Loo points out that although consumer behaviour has changed with the use of mobile and internet technology, the legal profession has not. “According to a study by Asia Law Portal in November last year, about 40% of those seeking legal services turn to Google as their first search point. However, this does not align with the number of law firms with an online presence in Malaysia.

“We did our own research by looking at the website of the Malaysian Bar to find out whether local law firms had any type of online presence, such as their own website, LinkedIn profile or Facebook page. We found that only one in four law firms had an online presence. Hopefully, we will be able to bridge this gap and bring the other 75% online.”

The idea for CanLaw was born of Loo’s own experience. “I was about to get married, so I wanted to purchase a nice condominium to move into with my then fiancée. Everything went swimmingly with the lawyer we hired until we were supposed to drawdown on the loan.

“Having already paid the 10% deposit, you can imagine how horrified I was when suddenly the lawyer called me and apologised, saying that his clerk had forgotten to do a bankruptcy check. That was when I found out that the seller was bankrupt and had used my deposit to pay off his debts — the money was already with the Department of Insolvency.

“This lawyer was recommended by a family member. I am not sure what would have happened if he had been a recommendation of an acquaintance instead. Thankfully, I eventually got my money back. But the process took nine months to complete. After the episode, I thought very hard about how finding legal services could be done better, especially now that technology is advanced enough for such innovations.”

The lawyer discovery concept is not new in the region. BurgieLaw in Kuala Lumpur and Asia Law Network in Singapore offer similar features. However, Loo says CanLaw differs from its competitors as it functions as a marketplace, whereas the other platforms function as directories with booking features.

“That means the users of our competitors still have to make multiple bookings and visits or phone calls to the different law firms before they can compare prices and expertise. On CanLaw, users can speed up the process and have access to three to five quotations at once,” says the CEO.

Users will also have access to the profiles of the lawyers on the platform. This feature is important as it allows users to make decisions based on other factors as well and not just the fees, says Loo.

“We are not trying to create a price war. So, users must not look only at the price. They have to be informed of the lawyers’ background, years of experience and areas of practice.

“Although a lawyer may charge you RM5,000 and another may charge RM10,000, the former may only have two years’ experience while the latter may have 20 years of experience. Also, some clients may be more comfortable with lawyers who can speak Malay or Mandarin, so this information is available on CanLaw.”

OBSERVING THE RULES

According to the Malaysian Bar’s website, there were 7,353 law firms and 20,040 lawyers in Malaysia as at February. CanLaw co-founder and chief operating officer Edwin Lee says law firms in the country have little to no online presence due to a lack of appreciation of the technology by the older generation in the profession.

“These law firms do not feel that they need an online presence because they probably have a comfortable pool of clients. Additionally, in the traditional notion of practising law, lawyers do not look for clients — the clients look for them,” he says.

“Despite this, the younger lawyers are a lot more entrepreneurial. They tend to see online presence as a way of getting more clients or increasing their chances of being headhunted by other law firms.”

CanLaw currently has more than 100 lawyers on its platform and receives two to five requests from users daily, which is more than the company had anticipated prior to its launch. According to Loo, the most requested service on the platform is for divorce proceedings.

“It is sad to see, but we receive this request almost every day. Maybe it is because it is something too sensitive to ask friends or family members. So, being able to search for help privately may have prompted this. Other popular requests include will drafting and property purchases,” says Lee.

The company has to do a lot of groundwork to get lawyers on board. It does not help that there are several challenges as well. According to Loo, the two main challenges are the industry’s perception and regulation.

“Some lawyers think we are out to disrupt the legal profession, but this is not true. We are enablers — we are working with them so that they can be found online. We are not competing with them,” he says.

“The other challenge is regulation. The legal profession is one of the oldest professions in the country. The Bar Council itself has been around since the 1940s, even before the country achieved independence. It is governed by strict regulations. If you look at the more mature countries, the profession has liberalised. Even foreign law firms, for example, are free to practise in those countries.”

For legal technology to take off in Malaysia, a clearly defined, engagement-based regulatory framework has to be set up, says Loo. “Just as how Bank Negara Malaysia announced the financial technology (fintech) regulatory sandbox and the Securities Commission Malaysia introduced guidelines for fintech, we would be more than happy to work with the regulators if they decide to introduce something similar.”

Of the eight employees of CanLaw, seven are legally trained. Although the company is not regulated by any of the regulatory bodies, it observes the Legal Profession Act 1976 to give comfort to the lawyers on the platform. This includes how lawyers promote their services.

“A couple of years ago, advertising was strictly not allowed. However, they recently relaxed the rule, saying that it is okay for them to advertise in publications that have been approved by the Bar Council or if the presentation of the content befits the dignity of the legal profession,” says Lee.

“So, we ensure that the lawyers’ profiles contain only approved information. For example, while they are allowed to specify their focus practice areas, they are not allowed to say they are the best in town.”

EXPANDING THE PLATFORM

CanLaw aims to get 20% of the lawyers in the country on the platform over the next three years. Thus, it is actively engaging with lawyers to ask for their participation.

“Getting 20% on board is a good, realistic benchmark for us. Of course, it is not ideal. But the process is quite difficult as lawyers are not exactly keen on adopting technology. Nevertheless, we will do our best to meet and exceed this,” says Loo.

One of the features of the platform is the CanLaw report. This section of its website provides articles on legal matters that are written in an entertaining manner.

“We produce two articles per week. The aim is to educate the public. Legal articles tend to be very heavy. People do not read them until they need to for research. Thus, we avoid using jargon and write in a manner that it can be a light read for everyone,” says Loo.

A feature that the CanLaw team is considering adding is a rate and review function for the law firms, similar to that used by Uber and Airbnb, to add transparency to the legal service discovery process. The company is seeking feedback from lawyers on whether the feature would be in their best interests.

“Some have given positive feedback. They see it as an asset that would drive more traffic to their business. But of course, at the other end of the spectrum, there is hesitation about careers being potentially harmed by bad ratings. If we decide to go ahead with this feature, we will make sure it is tastefully done, perhaps by giving them the choice to be rated or not,” says Loo.

The platform’s services are currently free for both lawyers and those seeking legal advice. But the company is seeking approval from the Bar Council to charge lawyers a nominal administrative fee for listing on the platform, just as how lawyers are charged for a listing in the Yellow Pages, says Loo. If the company’s request is not approved, it will look at other avenues such as advertising or pivot its business model to other law-related areas.

Prior to launching its platform, CanLaw participated in Khazanah Nasional Bhd’s pre-accelerator programme Project Brainchild Start-up and

competitions organised by several corporations. The company was the first legal tech recipient to be offered a grant under Cradle Investment Programme’s Catalyst. In January, it became an affiliate of Brickfields Asia College.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.