Prices of Ming dynasty porcelain have risen substantially in recent years, owing to renewed interest in these works of art, especially by Chinese investors. In this second part of a two-part series, Jennifer Jacobs talks to curator Jessica Harrison-Hall who shares more pointers for investors.

JESSICA HARRISON-HALL is the British Museum curator for the Department of Asia and a world expert on Chinese ceramics, with a particular affection for those produced during the Ming dynasty. She has written several books on the subject and curated several key exhibitions.

She has taken note of the increased interest in Ming ceramics over the recent years and recently curated an exhibition entitled "Ming: 50 Years That Changed China", which she is keen to talk about.

“We chose that period because it was sandwiched between two very dramatic events — the first was the Civil War between 1399 and 1402, which brought the Yongle Emperor to power, and the second was the capture of the Zhengtong Emperor in 1449. It was also a period that saw the flourishing of multiple courts across China, when the capital moved from Nanjing to Beijing.

“It had a series of princely courts, which my co-curator (Craig Clunas, professor of history of art at the University of Oxford) had previously done some important research on, and we wanted to bring out the connections between these courts and how globally engaged they were.

“This period is also important for the voyages of Zheng He. It is the period when this eunuch admiral and other eunuchs were sent on imperial commissions — voyages from China all the way to the Middle East and the east coast of Africa,” Harrison-Hall says in a telephone interview.

There have been some fairly recent archaeological discoveries dating to just precisely this period, she adds. “I am thinking particularly of the material from the Hubei province. We wanted to have the Zaoyang tomb finds included in the exhibition. And it is also a period where you have this wonderful flourishing of the material culture of China. So, you have some of the best porcelain in the world, the most beautiful lacquer, fabulous jewellery, textiles, sculpture, costumes and so on. And so for these reasons, we picked this period.”

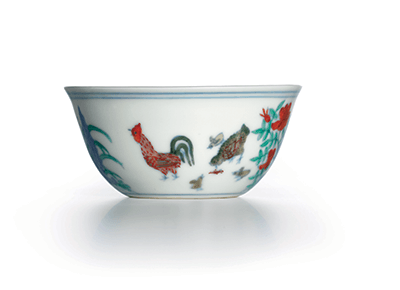

Being passionately engaged with the cultural and historical significance of Ming ceramics, Harrison-Hall does have some advice for anyone keen on taking this up. “You have to remember that these things were mass-produced 500 to 600 years ago, so there are a lot of exciting things for people to collect. In the later period, you have the wonderful shipwreck materials, which come up occasionally at auctions, and throughout you have the imperial wares, a huge variety of things for people to collect, some of which are relatively inexpensive, such as the everyday storage jars from the Ming dynasty which one can pick up fairly cheaply compared with an imperial Chenghua Chicken Cup, which is right at the other end of the spectrum.

“Contemporary Chinese paintings are often vast, so you need to have a huge home with a huge blank wall to display them. But you can display a beautiful Ming vase in quite a small apartment. So, there is really something for everybody,” she says.

But as always, it is a matter of personal preference. “Always buy what you like. Don’t buy something because you think it will go up in price. Just go by your own reaction. There are lots of interesting books out there on ceramics and their history. Build up your eye by visiting auction houses and see things, handle them if you can. And if something is too cheap to be true, it probably isn’t worth it,” says Harrison-Hall.

As she has written extensively on the subject, she recommends her own books for anyone keen on getting a feel of Ming ceramics. Firstly, there is the definitive Ming Ceramics in the British Museum, published in 2001. Then, there are two that came out last year, Ming Art, People and Places and Ming: 50 Years That Changed China, co-written with Craig Clunas, which accompanied the exhibition of the same name.

“There’s a good book by Eva Ströber called Ming, and another by Stacy Pierson called From Object to Concept: Global Consumption and the Transformation of Ming Porcelain,” she says.

But to appreciate Ming ceramics, you have to go to museums and enjoy the collections. “All the museums in the UK are free to visit and lots of them have ceramics collections; the British Museum of course, but also the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. In China, you have the Shanghai Museum, the Palace Museum, the National Museum of China, the Guangdong Museum and the Hong Kong Museum of Art,” Harrison-Hall says.

At the end of the day, she points out, these ceramics are not just works of art; they are a way of understanding that particular era. “You look at the ceramics and they can give you a sort of key to history, sometimes. You can think about the sort of preoccupation of the people at the time. Or you can think about the context in which the ceramics were used — where it was used, who used it, why it was made, who made it and how it was shipped.

“All these things can lead you on a journey of social history, economic history and architecture. They are sort of a key to unlocking all sorts of facets of history.

“And what is really interesting is to look at them in combination with text [from the period]. Sometimes, you can gain things from inscriptions on ceramics which are simply not there in the text, and sometimes things which are there in the text that are not there in the material culture. But by looking at them both together, we get a better picture of Chinese history at the time.”

This article first appeared in Personal Wealth, a section of The Edge Malaysia, on February 23 - March 1, 2015.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.