This article first appeared in Digital Edge, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on September 20, 2021 - September 26, 2021

Genome sequencing on positive Covid-19 samples in Malaysia can and should be done more frequently and faster, says Dr Gan Han Ming, chief scientific officer of Geneseq Sdn Bhd. This is so that we can observe the dominance of variants of concern (VOC) like Delta and identify new variants, like the Mu variant, before it is too late.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) of the virus takes eight to 14 days, said health director-general Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah in a Facebook post on Aug 1. While waiting for those results, the Institute for Medical Research (IMR) has been using genotyping assay, which takes four hours, to generate presumptive results.

According to reports, by late July, the IMR and other agencies had only run genomic sequencing on 0.17% (or 1,700 out of one million) of the positive cases in Malaysia. The total number of cases by the end of July crossed one million. Another 265 samples were sequenced in August, most of which were from Sarawak, all of which were of the Delta variant.

In contrast, the UK had sequenced the genomes of 894,510 positive samples as at Sept 2, 2021 (or roughly 13% out of a total of 6.8 million positive cases).

Gan argues that the genome sequencing process can be done faster. He has a decade of experience in next-generation sequencing, using the Illumina and Oxford Nanopore sequencing technologies in academic and industry settings. Geneseq provides genome sequencing services to sectors such as agriculture and aquaculture.

Instead of sequencing the entire genome of the Covid-19 virus, says Gan, the researchers could focus on sequencing only the gene encoding the spike protein (S-gene) for now, since that is the unique identifier of different variants. He has experimented using this method with around 24 Covid-19 positive RNA samples provided by his collaborators from the Klang Valley and Pahang, and the results have been 100% accurate, he says.

“Our approach is simple. We make targeted copies of the spike protein gene fragments and read the DNA sequence. With that, we can, with confidence, say what kind of mutation it has and whether it’s identical to the currently reported variants.”

The approach is fast and scalable, Gan adds. A hundred samples can be sequenced at a time. The results could be available in a day if the samples were received in the morning. “From the moment we receive the RNA sample, we can do the targeted amplification, which takes three to four hours, and the sequencing can be done in an hour.”

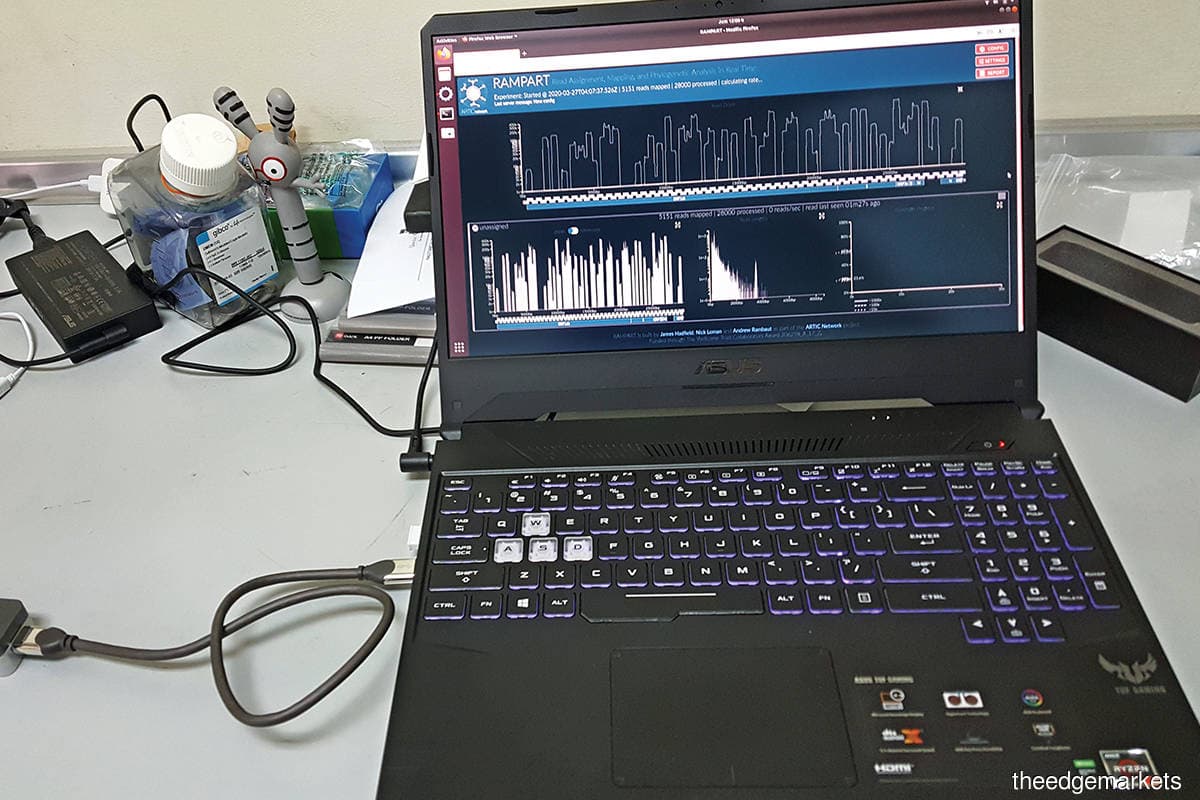

Gan is in favour of using the palm-sized Oxford Nanopore sequencing device to do this. The device is portable and can sequence genomes in a shorter time than the bigger Illumina machine, he says.

The sequencing process using the more widely available Illumina machine could also be faster. In some cases, researchers culture the virus sample first by infecting lab cell lines with the virus before sequencing it, says Gan. But that takes time. Given the current situation, he believes that the virus samples can be sequenced directly.

“Similar to how we are now detecting Covid-19 in the community, you can also use the RT-PCR approach to selectively amplify only the virus genetic material. This way, you can get more coverage of the viral genome. When you have the virus-infected cell culture, a big majority of your sequencing data is from the host [instead of the virus],” he says.

Digital Edge asked Datuk Professor Dr Awang Bulgiba Awang Mahmud, an expert epidemiologist at Universiti Malaya, via email, on what he thought of the method Gan suggests. Awang is among the experts who have been vocal about the need for more genomic surveillance of the Covid-19 virus in Malaysia.

“Many of the important mutations (the ones that affect transmissibility and possibly antibody evasion) occur in the spike protein and, thus, instead of whole genome sequencing, sequencing the spike protein can possibly offer a faster way out. However, for a more detailed explanation, I would recommend asking a virologist,” Awang says.

He is sure that the process of genome sequencing can be expedited as long as more funds and samples are provided for universities, which have genome sequencing facilities, to help out in the effort.

“There is also the question of integrating the genome sequencing data into epidemiological analysis. For more meaningful analysis and for this to contribute to pandemic management, this data needs to be analysed with other epidemiological variables. Unfortunately, data sharing in Malaysia is very poor, so this does not happen,” he says.

A good example of this is how the Covid-19 Genomics UK Consortium works closely with Public Health England, which issues technical briefings based on their combined analysis.

Wait, why is this important?

Genomic sequencing of positive Covid-19 samples can tell us what are the dominant VOCs or variants of interest (VOI) in the country. This information can be vital to help manage the pandemic.

For one, it could be used to track clusters caused by different VOCs and stop the virus from being spread. Second, since the Delta strain is more infectious and deadly, patients infected with this strain could perhaps be isolated from others and given different treatments, observes Gan.

Additionally, frequent and routine genomic surveillance of Covid-19 in Malaysia could inform authorities whenever new strains — including potential local strains — show up in the country, and prompt them to take immediate action. It could also be used to study the resilience of vaccines to different strains.

Real-time information about the proportion and distribution of different VOCs in Malaysia is important, Gan emphasises. It should not be seen as a retrospective or academic study of the virus but instead something that is current and used to complement actions by the authorities.

“Given the situation currently, it’s not surprising to think that Delta is on the rampage already. I believe that having more information about the distribution of VOCs at any hospital or cluster gives you a better idea of how to manage the situation,” he says.

He was referring to the seeming disconnect between official data and the situation on the ground in late July, when cases in Malaysia, especially in the Klang Valley, soared beyond 10,000 per day.

At the time, Malaysia had only recorded 429 cases being VOC or VOI, 46.2% of which were Delta, according to the World Health Organization’s Malaysia Covid-19 situation report. Most cases bearing the Delta variant were detected in Sarawak, although cases and deaths were highest in Selangor then.

Fortunately, the government has been taking note. In July, the health minister at the time, Dr Adham Baba, announced the government’s intention to increase Covid-19 genomic sequencing to more than 1% of positive Covid-19 cases in three months from August. Up to RM3 million will be allocated to a consortium of seven universities and laboratories to run genomic sequencing on 3,000 samples.

However, this is still a very small number compared with the number of daily new infections, says Awang. “Malaysia’s genome sequencing is too small and too slow to contribute to its pandemic management. I have long called for increased genome surveillance so that pandemic management can make use of that data.”

Can the private sector step up to help? Gan says he is open to helping if they (authorities) need consulting, since he believes IMR and the universities have the necessary technology already.

“What I’m proposing is that there is a faster way of doing it. I advocate for more sequencing but if we keep following the currently reported approach, it is not fast enough. We need real-time data. We’re happy to share what we know,” he says.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.