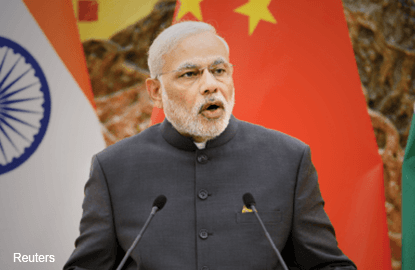

A year ago, newly elected Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was promising to do big things, including amending a law that made it unreasonably difficult for companies to acquire land for factories and infrastructure projects.

He has more or less given up on that particular ambition, after stumbling into fierce resistance in the opposition-dominated upper house of Parliament. The climbdown comes just as gross domestic product growth slowed to 7% in the second quarter, disappointing those hoping India would shoot past a faltering China to become the world’s fastest-growing major economy.

Modi needs to change this souring narrative, and fast. Individual states might still be able to push forward much-needed reforms in land and labour. But at the national level, the opposition has succeeded in painting Modi’s agenda as pro-business and anti-poor. That’s a precarious place for the prime minister to be in, especially with politically crucial elections coming up in largely agrarian Bihar state.

Part of the problem is that Modi, despite his fabled skill as a communicator, has failed to explain to poorer Indians how reform will benefit them in addition to well-connected tycoons.

He might have better luck if he sets aside the most controversial issues for now and focuses instead on sectors — among them, education and healthcare — that affect the masses more directly.

Radical reform is required in these areas as well. As a 2014 McKinsey report noted, half of public spending on basic services in India never reaches ordinary citizens. While primary and secondary education is free, the quality of public schools is atrocious: Over 90% of Indian children are enrolled in primary school, but that number drops to 36% by the time kids reach the upper secondary level.

Similarly, access to healthcare is poor. India has only one doctor for every 1,700 people — well below the World Health Organization’s recommendation of one for every 1,000. At 66 years, India’s life expectancy ranks the country at 139 among 194 nations, lower than nations like Bangladesh and Indonesia.

As McKinsey notes, there’s no dearth of good ideas for how to improve outcomes for students and patients. The focus on providing free public healthcare has stretched resources too thin.

A better strategy, suggested last week by the government’s own think tank, Niti Aayog, would be to shift to an insurance-based system. Citizens would all contribute to a “sickness fund” and then be reimbursed for care, regardless of whether they visit a public or private hospital.

Modi’s government proposed a similar system for life and accident insurance last year, allowing the poor to access benefits for a nominal premium. The government could provide vouchers to aid the very poorest.

A voucher system would also help schoolchildren. Government schools suffer not just from a lack of funding, but also from weak teachers. A World Bank study found that 25% of teachers didn’t show up to school and only half were actually teaching classes. Giving parents the freedom to choose schools — whether public or private — would encourage competition and hopefully improve quality at state schools.

Importantly, one of the government’s central successes thus far has been to build the foundations for such reforms, which require transferring cash directly to patients and parents.

Over the last year, the government had opened 175 million accounts for the formerly unbanked. The Aadhar system of unique identity cards, launched under the previous government, now covers 870 million people.

Officials can be reasonably confident that they can target cash vouchers to deserving recipients without money being skimmed off by middlemen. The cost to the government would be far less than trying to revamp the public education and healthcare systems from scratch.

Even poor Indians have shown they are willing to pay for private-sector clinics and schools, despite sometimes steep expenses. Rather than fighting this trend, the government should clear away the red tape which prevents new facilities from being built. That would bring costs down, while direct aid would help the poorest afford fees.

These might seem like radical ideas to some in India. That is the point: Reform doesn’t only mean making life easier for industrialists. Such changes would have an immediate impact on the lives of the poor, even while creating efficiencies throughout the economy.

Modi could begin right away by launching pilot programmes in states controlled by his Bharatiya Janata Party, which might allow him to post a few quick wins. At this point, he has little to lose. — Bloomberg View

This article first appeared in digitaledge Daily, on September 8, 2015.