This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on July 18, 2022 - July 24, 2022

Integrating environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into executive remuneration is the right move for companies. If done badly, however, it could leave companies worse off, says Mak Yuen Teen, professor (practice) of accounting and former vice-dean of the NUS Business School, National University of Singapore.

In May, Mak published a report titled “Integrating ESG factors into executive remuneration” in collaboration with the Sustainable Finance Institute Asia (SFIA) and CPA Australia. The report points out potential pitfalls when linking ESG factors to executive remuneration.

One example is of companies that are overly aggressive in remunerating CEOs based on ESG factors. These non-financial performance measurements could be the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from business activities or, in the case of an oil and gas company, reducing the number of oil spills into the sea.

Why? It could create the perception among stakeholders that a company is giving its CEO leeway to be rewarded with huge bonuses by hitting “easy” ESG targets, especially when the company is in poor financial health.

“If, all of a sudden, a company increases the weightage [of ESG factors linked to CEO remuneration] from 0% to 40% while doing poorly financially, it could create the perception that you’re just giving a ‘soft landing’ to your executive [to get large bonuses],” he explains.

Another pitfall is the use of ESG metrics that are incomprehensive. For instance, Marathon Petroleum, an American petroleum refining, marketing and transport company, awarded its CEO US$272,000 (RM1.2 million) for meeting environmental goals in the same year it spilled 1,400 barrels of fuel into an Indiana creek. This was its worst oil spill incident in recent years.

The bonus was given because the company’s top executives were assessed based on the number of significant oil spill incidents in a year, instead of the total volume of oil spilled into the sea.

“Companies should clearly identify a few material ESG factors that they want to focus on and develop appropriate metrics to capture those factors,” says Mak. “They need to know what they are going to measure and weigh. When they can do that, they can increase those weightages [linked to ESG factors] over time.”

Additionally, companies should not be too formulaic in measuring the CEO’s performance in relation to ESG factors. A certain degree of discretion should be allowed, as the company’s expectations of its ESG targets and that of its stakeholders may differ.

Take Starbucks, for example. Former CEO Kevin Johnson was offered a US$50 million retention bonus by the company. But that move did not win the support of its investors. Subsequently, Starbucks revamped its bonus packages and added new environmental and human rights criteria to its CEO remuneration policy.

Ten per cent of Johnson’s annual bonus was tied to environmental provisions, such as eliminating plastic straws and reducing farm-level methane, with a further 10% tied to retaining minority workers and more. Johnson achieved all his bonus targets, including those related to ESG factors, and received a total pay of US$20.4 million in 2021, a substantial increase from US$14.7 million in 2020.

Ironically, Starbucks later announced that Johnson would be retiring (on April 4, 2022, with former CEO Howard Schultz returning as interim chief). That was right after Starbucks employees formed its first worker union in the US and accused the company of “union busting”.

Starbucks faced a federal labour charge filed by its workers, claiming that the company is involved in illegal activities such as engaging in threats, intimidation and surveillance related to the attempt of its workers to form a union.

Mak says the Starbucks case is one where a company CEO met the firm’s ESG targets, while also facing discontent from investors and employees.

“At the end of the day, it is about balancing objectivity and discretion. You cannot become totally formulaic without a certain degree of discretion,” he says.

Transparency is key

Transparency is a crucial element in linking ESG factors to CEO remuneration. It is also an element sorely lacking among Asean companies.

Mak, who has studied remuneration practices of public-listed companies in Singapore, says many companies in the city-state — especially those controlled by business founders and their families — still measure their CEO performance based on traditional metrics, such as business profits. Some may claim that they link ESG factors to their CEO remuneration, but details of the linkage are scant.

“Many [companies] claim that they use non-financial measurements [for their CEO remuneration]. But when you actually track their annual bonus, you find that their remuneration is highly correlated to their profits,” says Mak. “A lot of them are actually adopting a profit-sharing model. We need to be a little bit careful when a company says it links ESG to remuneration.”

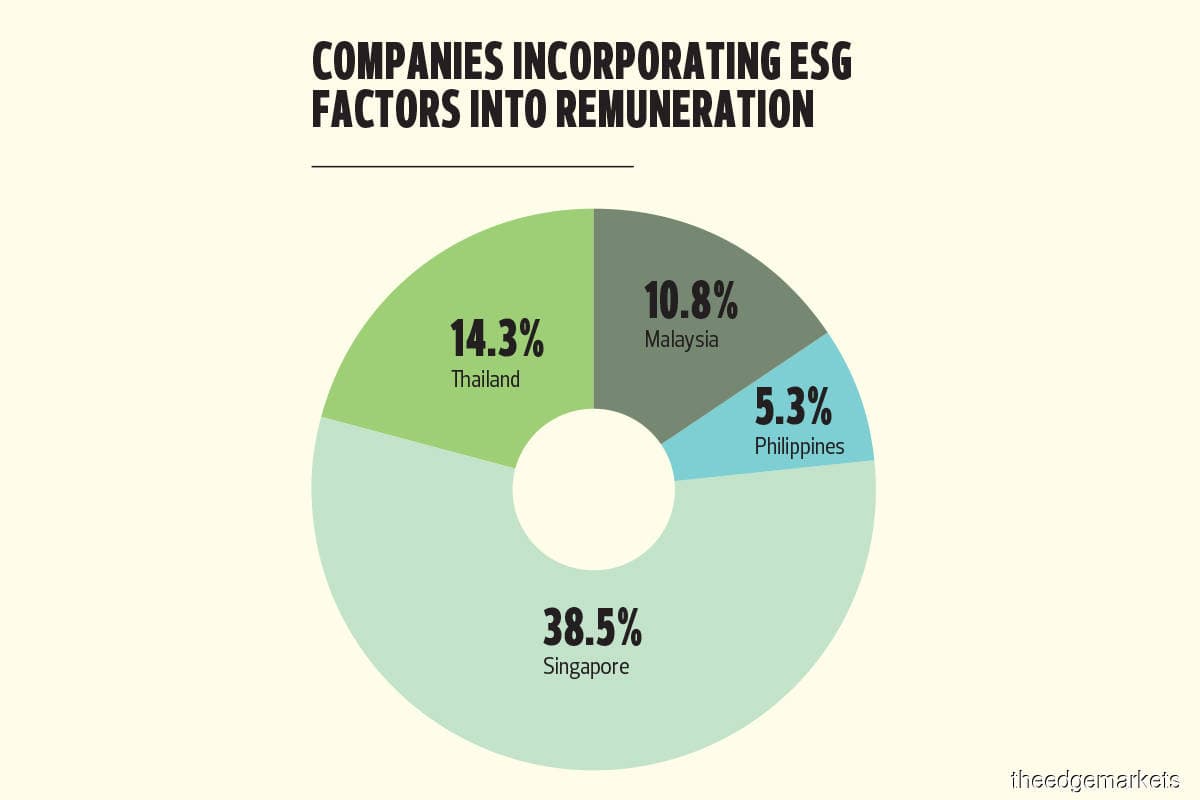

He points out that companies in Asean are only starting to integrate ESG factors into executive remuneration. For instance, among the 135 companies in the region named as “Asean Asset Class” companies in the 2019 Asean Corporate Governance Scorecard Awards, only 21 (or 16%) explicitly disclosed that they link ESG factors to executive remuneration.

The highest percentage of companies doing so is in Singapore (see chart). Most companies linked environmental factors to remuneration, followed by social and governance factors. But overall, specific details on how ESG factors are incorporated into executive remuneration are scant, Mak says.

In Malaysia, Mak singles out Top Glove Corp as a good example. The company began this initiative during the pandemic. According to Mak’s report, Top Glove mentioned a 40% linkage of ESG metrics to its management pay for FY2021.

“I would say Top Glove is the most transparent in showing how it assesses material ESG factors and the key ESG metrics that it uses [that are linked to its executive remuneration]. They show the weighting [of each metric] and how they are measured. Very few companies do that, even in Singapore,” he says.

“Yet, we find that Asean companies are not consistent in their transparency level. Some of them show the metrics they use, but don’t show the weighting. Other companies like Top Glove show the weighting and measures, but are still not as transparent as some multinational corporations like Shell and BP.”

Board of directors needs to have right mindset

Eugene Wong, CEO of the SFIA, adds that companies need to have a long-term view and mindset to implement ESG-related strategies, including integrating ESG factors into CEO remuneration.

“The company’s board really needs to think clearly about where the company is heading and how they want it to be sustainable. They can’t say, ‘Oh, our share price is not up, and our financial performance is not where it should be. Let’s scrap our ESG initiatives,’” says Wong.

It is important, he says, that the board of directors understand the importance of ESG and ensure that their vision is aligned with that of the CEO.

“I was talking to a director of a listed company. He told me that he went for this board meeting, where the chairman appeared to know little about ESG and focuses mainly on profits. When the director asked the chairman about ESG-related matters, the chairman said, ‘Oh, it is part and parcel of our business to have some pollution. It is just like that,’” says Wong.

“In short, the chairman is not concerned about suggesting things like finding a more efficient way to manage the effluent released by the company. In his mind, his business produces effluent, and he must not get caught by the authorities. Things won’t change if all directors belong to a club and agree with the chairman.”

Meanwhile, fund managers need to play a more active role in pushing companies to be more ESG-compliant, says Wong.

Priya Terumalay, CPA Australia’s country head in Malaysia, adds that companies, organisations and accountants need to be clear about what they convey to their stakeholders through financial reporting disclosures.

“Organisations should also be mindful that ESG and broader sustainability-related considerations do not become a tick-the-box exercise,” she says.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.