LAST year, when the ringgit depreciated sharply against the US dollar, former Bank Negara Malaysia governor Tan Sri Dr Zeti Akhtar Aziz reiterated at every press conference that the country’s fundamentals were intact and that the ringgit’s volatility was largely triggered by external factors beyond anyone’s control.

Just as Malaysians started to believe that the ringgit might have found its base against the US dollar, volatility struck again. This came after Americans elected business mogul Donald J Trump as their 45th president two weeks ago. The ringgit has depreciated 5% since he won the White House, becoming the worst-performing currency in the region.

Once again, the fear brought about by the weakening local currency spread among Malaysians, who wondered whether the country’s fundamentals had been eroded further. Is Bank Negara’s claim — that the ringgit’s movement is due to external noise — true?

If it is any consolation, the local currency was not the only one to falter after the US election. Many emerging-market currencies have visibly weakened against the greenback.

“Trump’s ascent is viewed as negative for Asia due to three areas of concern — trade, currency and regional geopolitical developments. We have assumed a ‘soft’ Trump scenario in recent recalibrations of foreign exchange and rates forecasts,” says United Overseas Bank (M) Bhd economist Julia Goh.

“The soft Trump scenario is that Trump does not fulfil all his campaign promises, or about 50% of his pledges and mostly non-radical measures. However, admittedly, there is a lot of uncertainty and the main thing to watch for is the people he brings on board and his actions post-inauguration on Jan 20, 2017,” she adds.

Besides the Trump factor, the ringgit has been a victim of several other external factors since mid-2014, namely falling crude oil prices, a stronger US economy and the likelihood of an interest rate hike by the US Federal Reserve.

Nevertheless, external factors should not bear all the blame. Who could forget the 1Malaysia Development Bhd controversy that lingered on for a good part of last year? It certainly did not add to the ringgit’s attractiveness. The ongoing investigations internationally into the strategic investment fund have not helped matters.

The sovereign rating of a country’s bonds can influence the attractiveness of its government debt and, indirectly, capital flows. This could, in turn, affect the local currency’s strength.

Moody’s, in its 2017 outlook report, says its outlook for sovereign creditworthiness globally next year is negative overall.

“The key drivers of that negative outlook are a combination of continued low (economic) growth, high public-sector debt — which will likely rise further with expansionary policies — and domestic and regional political tensions that adversely affect the development and implementation of public policy.

“Some emerging market sovereigns face the added risk of capital outflows. As a result, 26% of Moody’s-rated sovereigns currently have negative rating outlooks, the largest proportion since 2012, while only 9% have a positive outlook,” it says.

Moody’s has a stable outlook on Malaysia with a rating of A3. However, the rating agency highlights the country in its report as one of the emerging markets with limited room for manoeuvre in terms of interest rates because any aggressive monetary easing could trigger large capital outflows.

It is a concern for Malaysia given the high foreign holding of the country’s government debts — about 52% at present — which makes it more vulnerable to the risk of capital outflows.

“Asian central banks may be in a challenging position in 2017 as raising rates will worsen the growth outlook while further easing will widen rate differential between them and the US, and may add to capital outflow pressure. The most likely outcome is for Asian central banks to stay ‘low for longer’,” says UOB’s Goh.

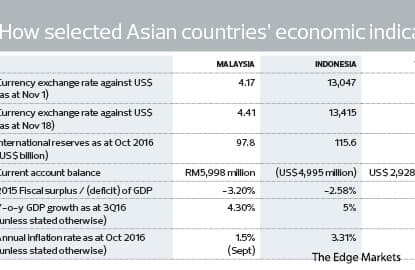

Malaysia’s international reserves dipped significantly to US$97.8 billion as at Oct 31 compared with US$133.2 billion in January 2014. However, they have recovered from their low of US$85.28 billion in September last year.

Its reserves are still lower than neighbouring countries such as Thailand and Indonesia. As at Oct 31 this year, Indonesia’s reserves stood at US$115.6 billion while Thailand’s reserves were at US$180 billion.

An economist from MIDF Research says at the current level of US$97.8 billion, Malaysia’s reserves are still higher than the period prior to the quantitative easing programme in the US.

“There is no such thing as our reserves needing to be more than US$100 billion,” he says, referring to the psychological level that is often cited.

That aside, economists opine that the ringgit remains fundamentally strong. The currency’s strength has to be looked at alongside the country’s economic indicators, given that its value is supposed to be backed by the country’s economic performance.

“The ringgit is fundamentally strong if we’re backing it up with Malaysia’s economy. Our gross domestic product (GDP) growth is still stronger than the global average, our current account is still in a surplus while our inflation rate and unemployment rate remain low,” says the MIDF economist.

“Overall, it reflects that Malaysia’s economy is still fundamentally strong and should continue to attract foreign investors into the country.”

Goh concurs, adding that nothing has changed as far as the economy is concerned. However, she warns that should the ringgit’s weak performance continue, it could have negative spillover effects for the broader economy.

“It is hard to argue the benefits of a weaker currency for trade competitiveness when global trade is still weak and commodity prices low,” she says.

Malaysia’s third-quarter GDP growth came in above expectations at 4.3% year on year compared with the 4% y-o-y growth in the second quarter. While it is an improvement, it has nonetheless slowed from 2015, when the full-year GDP growth was 5%.

However, compared with the other emerging economies in the region, Malaysia’s GDP growth is one of the lowest. The Philippines led the way at 7.1%, followed by Vietnam (6.4%) and Indonesia (5%). Thailand has yet to release its numbers but its second-quarter GDP growth was only at 3.5%.

Meanwhile, Malaysia’s current account surplus stood at RM5.998 billion in the third quarter, widening from RM1.884 billion in the previous quarter. However, it was not even one-third of the RM19.8 billion seen in the first quarter of 2014.

While the country’s economic fundamentals look intact, in the view of some economists, the ringgit is likely to remain volatile for the time being.

“The depreciation of the ringgit currently is purely due to speculation on the actions that will be taken by president-elect Trump and the Fed in the future. Any hint and new information on the issue could cause the ringgit to move. Another issue is the Opec (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) meeting on Nov 30, when they will decide whether they will actually freeze their production output,” says the MIDF economist.

“At the moment, forecasting the ringgit will require forecasting many political and economic decisions, which is currently difficult to be made.”

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.