This article first appeared in Enterprise, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on December 25, 2017 - December 31, 2017

If Malaysian small and medium enterprises (SMEs) want to break into overseas markets, they should consider getting an international certification that will help them in their target markets, especially industries that deal with health and safety.

“We should not be looking at Malaysia only. Yes, it is our base and the customers here are the nearest. But it is always important to look beyond. There must be certain countries where your products are much needed. To penetrate these markets, you need to get your products certified, either at the country or regional level. This is especially the case in an industry such as ours, which deals with human lives,” says Lim Li Sze.

Lim is the co-founder of Medical Innovation Ventures Sdn Bhd (Mediven), which manufactures and sells diagnostic kits that detect diseases in the early stages. She says SMEs may have the perception that getting a product certified overseas is more expensive than doing so locally, and this may stop them from expanding their business abroad, but this is not necessarily the case.

“It depends on your products. For instance, we produce diagnostic kits that are able to detect diseases in the early stages. It was about 10 times more expensive for us to get our product certified locally than in the European Union (EU) in recent years due to changes in our country’s guidelines and regulations,” says Lim.

“Certification is very industry and product-specific. And it may not be more expensive to get certified overseas.”

Today, Mediven exports to the EU, Southeast Asia — including Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam — as well as Dubai and Peru. Getting its products certified was just the first step to enter these markets, says Lim.

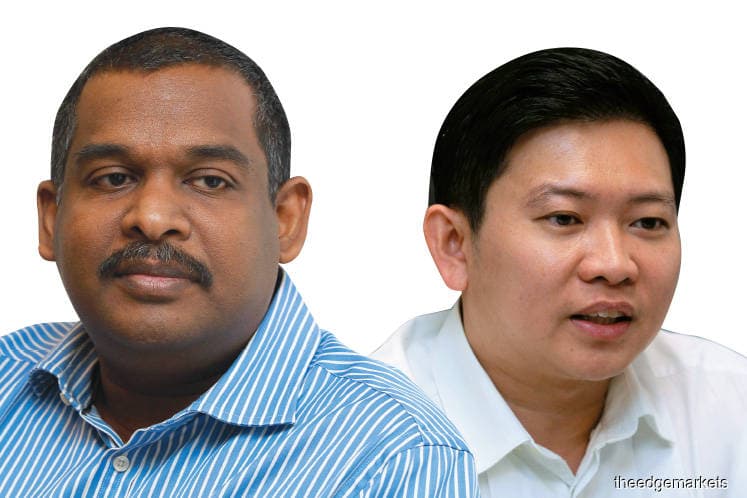

Sunderaj Nagalingam, group managing director of Dscaff Group, says local SMEs should take a longer-term view when it comes to product certification, depending on which sectors they operate in. While it could be challenging, getting their products certified overseas will not only enable them to enter foreign markets but also help them boost their business on the local front.

Take Dscaff, which exports its scaffolding products to several Southeast Asian countries and Australia. It recently made a breakthrough back home when it secured a purchase order from national oil company Petroliam Nasional Bhd (Petronas).

The key reasons for this, says Sunderaj, are that Dscaff is certified in developed markets and has managed to build a reputation overseas. “This is a very good example of how SMEs can benefit from getting their products certified locally and overseas,” he points out.

“Petronas had never purchased scaffolding on its own before. It left this to its subsidiaries and contractors. But now, it wants to make sure that the Refinery and Petrochemical Integrated Development (Rapid) project is perfectly safe. It bought the scaffolding from us simply because we are certified locally and overseas, even though our product is not the cheapest out there.

“After all, we are in the construction and infrastructure business and our products deal with the safety of construction workers. Getting certified is important.”

Sunderaj says the awareness of the importance of certification is rising on the local front, especially in the infrastructure sector as the government has been trying to reduce the fatality rate at construction sites. By getting their products certified in other developed countries, SMEs can build their reputation locally too and have an advantage when selling products to large corporations. “The government is emphasising product certification, which could trickle down to other industries as we move towards developed-nation status,” he adds.

Dr Voo Yen Lei, CEO of Dura Technology Sdn Bhd (DuraTech), says getting products certified depends on the industry the business is operating in and whether it plans to sell its products overseas. “It is very subjective. If you are selling products such as branded bags or Apple smartphones, you don’t really need a certification. But when it comes to health and safety, certification is a must.”

DuraTech has come up with its own technology to produce its own version of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC). The concrete, when used to build structures such as bridges, could increase their lifespan and make them more durable. Today, the company has exported its products to Canada and China.

Overcoming challenges

However, there are challenges to getting products certified, whether locally or abroad. This may explain to a certain extent why the majority of companies have been slow to avail themselves of the certifications that would allow them to enter new markets.

Mediven, for instance, had to hire a consultant from the in vitro diagnostic (IVD) industry (which comes up with tests that can detect diseases, conditions and infections) to help it understand the guidelines in relation to its product. The consultant read through the guidelines and advised the company on what it needed to do to comply with the requirements of the markets it wished to enter.

Engaging a consultant can be both difficult and expensive, especially for a company in such a niche business. “We found many consultants who specialised in things such as medical implants and surgical gloves. But there weren’t too many experts in IVD. Thus, it was very expensive to hire one,” says Lim. This cost could prove prohibitive, especially for a business that has just started out.

At first, Lim hired a consultant who charged less for his services. But this proved the maxim that you basically get what you pay for. When push came to shove and things got complicated, the consultant was unable to help the company manoeuvre around the intricacies of the certification process.

At this juncture, Lim decided to set up in-house expertise just to apply for the necessary certifications. “This actually makes sense as we are more familiar with our own products. So, we tried to do it ourselves, only asking for outside help when we had trouble understanding the guidelines. After all, we are in the best position to do it. We know our products best,” she says.

It proved to be a brilliant move. The company not only obtained its certifications but also managed to do so in the most cost-effective manner.

Lim is unwilling to reveal how much the company spent on the consultant, except to say that it ran into “tens of thousands of ringgit”. So, how much does a typical consultant cost?

“It depends on the clients. Some may want their manufacturing and packaging processes certified. So each year, they have to pay a firm to audit their processes to ensure that they are still compliant. The more people involved in the process, the higher the cost,” she says.

Dscaff’s Sunderaj faced the same issue. When he wanted to export the company’s products to Australia, he could not find local expertise to help get its products certified there. He ended up hiring an accredited engineer from Australia and flying him to Malaysia.

“We tried not to conduct the tests in Australia as we would have had to hire local labour over there, which would have increased our costs. We set up our system here and brought in the accredited engineer. This was the most cost-efficient way of doing it,” says Sunderaj.

Some clients did ask Dscaff to test its products in an Australian laboratory to get certified. But the cost would have been higher if it had done so.

Sunderaj faced a similar challenge when he was rolling out the company’s products in Malaysia. He could not find local guidelines that would allow him to benchmark the products.

So, he decided to set up in-house expertise to develop its own guidelines. He prepared all the necessary equipment, invited the local authorities to run tests and got the products certified, or invited a certified engineer to do the certification.

Today, the company has an independent team of about 13 people who take charge of matters related to certifications. The team ensures that the company’s more than 100 products are certified accordingly, based on the guidelines required in local and foreign markets.

“Certifications are not a one-off thing. The guidelines are reviewed every year and we need our team to make sure that our products are constantly tested based on the new guidelines as well as ensuring that the materials used are also updated,” says Sunderaj.

DuraTech’s Voo gets the company’s products certified in a different way. Instead of setting up an in-house certification team, he sells the intellectual property (IP) for this company’s product to a foreign partner, who will take care of all the certification matters.

“We sell them the technological know-how and teach them how to produce our UHPC product. From there, it is their job to make sure our product complies with the country’s guidelines and gets certified so that they can use or sell it in their markets,” he says.

This partnership can take several forms, says Voo. In Canada, the company sells its IP to its partner and collects royalties based on the volume of products used and sold. The products are sold under the DuraTech brand name.

In China, DuraTech set up a joint-venture company with its partner. So, instead of collecting royalties, it holds equity interest in the JV company in return for sharing its technological know-how.

When asked how he found these partners, Voo says he did not go looking for them. In fact, they came to him. “At the end of the day, whether your product takes off depends on how attractive it is and if the timing is right. Getting the right certifications is just the basic requirement,” he adds.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.