This article first appeared in The Edge Financial Daily, on October 1, 2015.

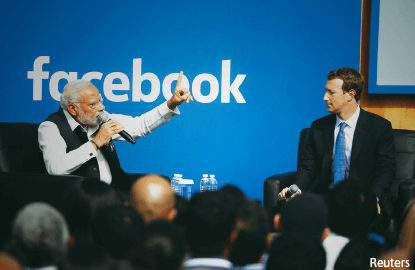

THIS past weekend, as India Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Silicon Valley, Facebook chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg announced that she’d updated her profile picture “to support Digital India” — Modi’s campaign to help connect India’s vast population to the Internet. “The more people have voice,” Sandberg enthused in a Facebook post, “the better things get for everyone.”

During his visit, Modi reciprocated by paying tribute to the digital platforms that have captivated millions of Indians. “Even when,” he said, “a child asks his mother to give milk, she says, ‘Wait, first let me forward this WhatsApp.’” Modi also hailed social media as a vehicle for democracy and urged world leaders to follow his example in exploiting it.

Certainly, a deft use of Twitter played some role in catapulting Modi from political purgatory to India’s highest political office. The Indian leader, who has yet to hold a press conference since his election in May 2014, now uses the service to speak over the heads of India’s mainstream journalists to his more than 15 million followers, energising them with reports of his meetings with top chief executive officers and world leaders.

The link Sandberg draws between cyber connectedness, individual empowerment and universal welfare, however, is facile. Digital technology has never been a neutral tool, notwithstanding the ambitious claims made for its democratising potential since the Twitter-aided protests by the Green Movement in Iran in 2009 — claims amplified after the Facebook-initiated demonstrations in Cairo’s Tahrir Square in 2011.

The Internet can be used as much to suppress voices as to mobilise them against despots. It’s as likely to aid malign propagandists as to disseminate life-saving news. In Turkey, from where I write, online trolls constitute a veritable cyber army for the country’s demagogic Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Egypt’s military ruler Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi now boasts his own loyal band of cyberattack dogs. Indeed, the devastatingly successful deployment of digital platforms by Islamic State should have revealed their dark ambiguity by now.

The Modi government’s own relationship to the Internet captures the latter’s double-edged nature. The same week Modi began his tour of the United States, his government shut down the Internet for three days in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, while Indian bureaucrats presented a draft policy paper suggesting that citizens should keep unencrypted records of every electronic communication for 90 days and present them to law enforcement officers on demand. (The much-mocked proposal was hastily withdrawn.)

A few months earlier, the government argued vigorously — if unsuccessfully — in India’s Supreme Court to retain a draconian law that Indian police had used to arrest people posting opinions on Facebook and Twitter.

Modi himself benefits from a self-appointed legion of cyber admirers, many of them Hindu supremacists. Their abuse recently forced one of India’s most respected television anchors off Facebook and Twitter; he had evidently outraged them with his coverage of the controversial execution of a Muslim convict.

Revealingly, Modi chose to launch the Digital India campaign by hosting around 100 of his most avid social media followers at his official residence. These diehard fans included, as a report in Caravan magazine put it, “people who have become a byword in online terror, hate and misogyny”.

While Modi counselled these loyalists to use more “positive” language in their posts, it remains to be seen if people accustomed to the mephitic depths of the Internet can rise to Google’s earliest motto: Don’t be evil.

Bringing more voices online is unquestionably beneficial for companies such as Facebook and Google that are in the business of commodifying personal data. It is less clear whether these corporations can combine their natural desire for expansion and profit in large untapped markets with a professed resolve to combat poverty, disenfranchisement and disease.

On the one hand, it’s true that the right kind of technology can help India leapfrog certain stages of economic development. On the other, those of us familiar with the state of Indian villages may wonder how the advent of fibre-optic cables will overcome basic problems of inadequate roads, drinking water, sanitation and, most importantly, lack of 24/7 power.

Success here greatly depends on how carefully Silicon Valley’s innovators choose their partners and parse their rhetoric, as well as how rigorously they monitor threats to individual freedom, dignity and privacy.

It’s above all crucial for them to understand the specific sociopolitical dynamics of the countries they deal with. Otherwise, practicable solutions to local problems will succumb to the boosterish and self-serving “solutionism” for which Silicon Valley has rightly been criticised. And its desire to do good, however sincere, will end up synergising best with demagoguery. — Bloomberg View

Pankaj Mishra is a Bloomberg View columnist.