This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on June 3, 2019 - June 9, 2019

SOME 10 years after the 2008/09 global financial crisis, it appears that banking systems in Asia-Pacific may still be able to count on a government bailout in the event of a meltdown.

According to S&P Global Ratings, most Asia-Pacific governments are still likely to support private sector systemically-important banks (SIBs) via bailouts should such institutions fail.

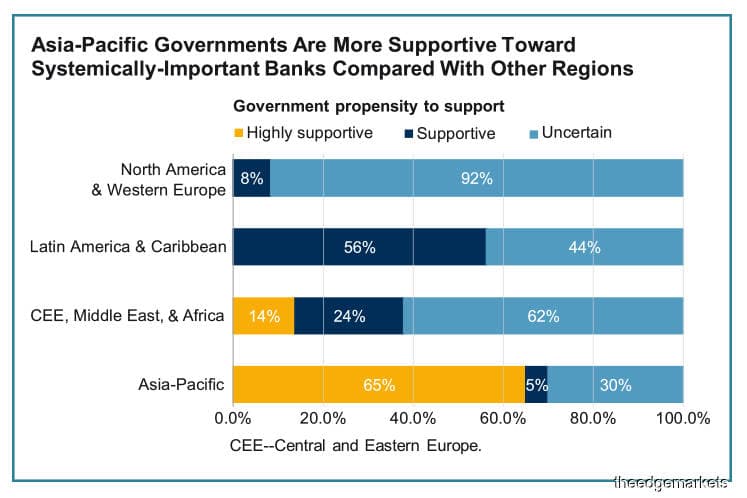

This is in stark contrast with North America and Western Europe.

“S&P Global considers a bailout continues to be the likely remedial action for G20 governments in the Asia-Pacific region in a bank crisis. Developments over the past one year, however, in the developed countries in the region, reflect the increasing intent of policymakers to consider bail-in as an option in the unlikely event of the potential failure of a SIB,” it says in an April 3 report on Asia-Pacific banking, titled “Despite different strokes, government lifeline still likely”.

Some jurisdictions outside the G20 are also considering alternative crisis management and resolution frameworks, it notes.

In S&P Global’s view, in 14 out of 20 Asia-Pacific jurisdictions — including Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia, China and Australia — the tendency of the governments is to support private sector SIBs.

“[In contrast], there are only two governments in the North America and Western Europe regions — that is, two of 24 — where we expect government support for SIBs. In all other countries in North America and Western Europe, government support is uncertain,” it says.

The S&P Global report highlights the stages of development of Asia-Pacific’s G20 jurisdictions over the past 12 months as they consider their implementation of the Financial Stability Board’s (FSB) “key attributes of effective resolution regimes for financial institutions”. The key attributes basically set out 12 core features of effective resolution regimes — such as resolution authority, powers and safeguards — that allow authorities to resolve financial institutions in an orderly manner without severe systemic disruption and without exposing taxpayers to loss.

In the 2008/09 global financial crisis, the US government injected US$700 billion into some of the biggest financial institutions on the basis they were too big to fail, drawing the ire of taxpayers. Bank of America, Citigroup and AIG were among the recipients of tax monies in the bailout.

The opposite of a bailout, a bail-in generally refers to a bank’s use of monies of its unsecured creditors, including depositors and bondholders, to restructure its capital so that the bank can stay afloat. This approach eliminates some of the risk for taxpayers.

This was illustrated in 2013 when depositors of banks in Cyprus lost billions after their savings were confiscated to protect the island’s banking system in a bail-in process. The move was a pre-requisite sought by international creditors as part of a €10 billion bailout of the country.

According to S&P Global, some of the developed markets in Asia-Pacific, including Hong Kong, Singapore and Australia, have gained “considerable ground” in resolution reforms over the past one year, while Japan is already “well progressed”.

But there has been little traction elsewhere, including in Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines and other Asean countries.

It is worth noting that of the 10 countries in Asean, only Indonesia is a member of the G20. Hence, the other nine countries are not party to a specific G20 agenda or timetable for consideration of FSB resolution and crisis management initiatives to address the too-big-to-fail issue that arose following the 2008/09 global financial crisis.

“A lack of progress in these nine countries (except in Singapore), therefore, is not so surprising. We note that Singapore volunteered to undergo an FSB peer review in 2017,” S&P Global points out.

Now that Singapore has given due consideration to new resolution initiatives, S&P Global believes more developed Asean countries will likely follow its lead. “In Malaysia, we expect a public consultation process will begin soon concerning resolution,” it says.

On April 3, Bank Negara Malaysia issued an exposure draft which sets out its proposals on a domestic SIB policy framework, for which it sought feedback from the industry. The policy framework forms part of the Basel III regulatory reforms.

In October last year, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) Act was amended to strengthen and enhance the powers of the central bank to resolve distressed financial institutions in an orderly manner.

While Singapore’s bail-in regime appears to be in line with most of FSB’s key attributes, the regulator has said that it has no plan to implement total loss absorbing capital, or TLAC, requirements.

“The MAS has chosen to adopt a less encompassing bail-in regime because it considers that its banks are already well-capitalised and subjected to stricter levels of capital standards than Basel. A further key feature of Singapore is to exclude the senior debtholders from the scope of bail-in powers,” S&P Global notes.

Analysts note that in Malaysia, during the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis, the government moved to help troubled banks via bailouts and other methods in order to maintain financial stability. It guaranteed deposits placed in banks, which helped depositors retain confidence in the banking system, unlike in other countries where bank closures had led to a run on the system and to capital flight. It also started off a consolidation agenda for banks.

The government also set up Pengurusan Danaharta Nasional Bhd, an asset management company, to handle the non-performing loans of banks, and Danamodal Nasional Bhd, a special agency, to recapitalise troubled financial institutions. Bank Negara initiated a merger programme, and by end-2000, 50 of the 54 banking institutions in the country had been consolidated into 10 banking groups.

“The goverment had no choice but to bail out banks then to prevent a systemic risk. But there were lessons learnt from that crisis, and since then, the central bank has further strengthened the financial stability framework and the banks have had to beef up their capital and so on. They are in a much stronger position, to the extent that when the 2008 global crisis hit, our banks were relatively unscathed,” Socio-Economic Research Centre executive director Lee Heng Guie tells The Edge.

He notes that Bank Negara also stress-tests banks twice a year to assess how they will hold up in the event of potential shocks.

In the event of a bank crisis in the future, should the government still opt for bailouts? “Maintaining financial stability is (of) utmost priority. Hence, Bank Negara is expected to take the necessary safeguards and create firewalls to prevent damage from systemic risk and failure,” Lee says.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.