BEIJING (July 22): China has suffered a series of diplomatic blows lately. Relations with the US are at a multi-decade low as a trade war escalates. This month, Malaysia suspended four Chinese-backed projects as its prime minister tries to pull away from Beijing’s orbit. From Myanmar to Sri Lanka to Vietnam, China’s overseas investments are being met with a growing backlash.

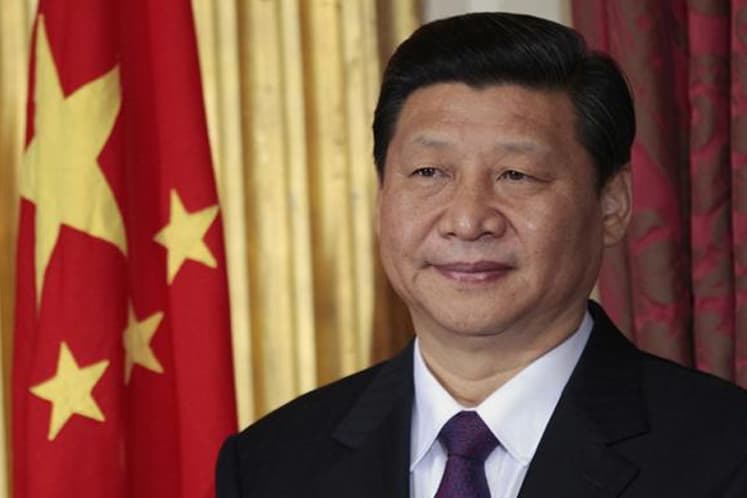

These are all setbacks to President Xi Jinping’s hopes for global greatness. Despite his aspirations to play the responsible world statesman, Xi’s foreign-policy record is filled with squabbles, misfires and unfulfilled promise. If he’s going to restore China to superpower status and cement its dominance in East Asia, he should take a cue from Chinese history about how to wield power.

For centuries, Chinese dynasties held a role in world affairs that looked very much like what Xi appears to want today. They sat at the center of an East Asian diplomatic and economic order that was stable, peaceful and prosperous over long periods.

That order was based on the “tribute system.” In the West, that phrase conjures up unsavory images of tyrannical emperors and cowering vassals. And it’s true that other East Asian countries were expected to acknowledge China’s supremacy. But the tribute system was also a sophisticated framework for diplomatic relations, with its own rules, customs and values.

The system was infused with the lofty principles of Confucianism, which acted as a governing ideology for China’s imperial court and a cultural glue that bound the region together. In the Confucian ideal, relations were hierarchical, but not unfair. The superior power had a duty to treat subordinates with kindness and wisdom. “When one by force subdues men, they do not submit to him in heart” said Mencius, one of the great Confucian thinkers. “When one subdues men by virtue, in their hearts’ core they are pleased, and sincerely submit."

China had the military and economic power to force its neighbors to kowtow, of course. But for the most part, the emperors showed restraint. From the founding of the Ming Dynasty in 1368 to the first Opium War of the 1840s, China invaded an East Asian state only once (an ultimately disastrous 15th-century push into Vietnam), notes David Kang, author of “East Asia Before the West.” In response, the other East Asian countries generally accepted Chinese hegemony; Japan’s ill-fated invasion of Korea in the 1590s was the only overt attempt to challenge Chinese supremacy in that entire period.

To the extent the tribute system worked, it was because all parties saw benefits from it, in trade and diplomatic support. Emperors often bestowed gifts on foreign embassies worth more to their vassals than the tributes they received. Occasionally, they made concessions when they didn’t have to. In 1725, when Vietnam moved part of its border about 40 miles north into Chinese territory to claim copper mines, the Qing emperor decided to compromise, leaving a majority of the land in Vietnamese hands.

Of course, the emperors were not always peaceful, especially with neighboring peoples to China’s west. But if Xi had Confucian scholar-officials in his court, like the old emperors, they’d likely advise him to act with more patience, generosity and conciliation — and thereby get foreign leaders to cooperate with him willingly.

What would that mean in practice?

For one thing, China would refrain from further militarizing disputed areas of the South China Sea, and instead sit down with the other claimants, maybe giving an inch or two to reach a compromise that gained foreign support while maintaining China’s dominance. To resolve the trade war with Washington, China could focus on the very Confucian principle of reciprocity, and be willing to treat foreign companies on its turf the way its companies are treated overseas. And with Belt and Road, Xi could be more magnanimous and share the programme’s benefits more evenly with its participants, thereby avoiding a popular blowback.

Xi obviously shouldn’t reestablish the tribute system; he couldn’t if he wanted to. But the emperors and their Confucian literati did know a few things about prudent leadership. Just because you have power doesn’t mean you should use it. Superpowers must sometimes make sacrifices to sustain their stature. And a little Confucian benevolence can go a long way.