KEEPING Greece within the eurozone and the European Union (EU) is a political question. Yet it’s also about money, and it may be worthwhile to consider how Europe would act if it is a bank confronted with a big delinquent debtor.

This would be an easy question to answer if the choice is merely between a Greek default on all of its debt and a write-off of some portion.

Yet the situation is more complicated: Greece wants €53.5 billion (almost RM226.35 billion) over the next three years. Would a banker lend that sum to retain a chance of hanging on to some of the money already invested?

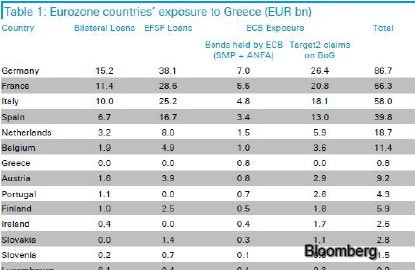

Calculating how much European countries would lose if Greece is cut off is not straightforward. They are seriously exposed in four ways: through straight bilateral loans issued as part of the first bailout in 2010; through guarantees on loans issued by the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the EU bailout fund; through the European Central Bank’s (ECB) holdings of Greek bonds; and through Target2, the ECB’s settlement system in which all euro members have outstanding claims on Greece.

It’s doubtful that the Target2 claims, a total of €100.3 billion, should even be part of the equation. Four non-euro countries, Bulgaria, Denmark, Poland and Romania, are part of the system, and even if it drops the currency, Greece will still do a lot of trading in euros. Besides, part of that exposure is collateralised. A banker would only worry about the rest of the debt, €211 billion at face value.

A Greek default on the bilateral loans would mean a straight loss to the creditor nations, but it would fall under the classic definition of sunk cost: The countries won’t have to plug a hole in any balance sheet by borrowing more, they’d just never get back their €52.9 billion.

That would be painful, but the payments are spread over 22 years, starting in 2020, andz the interest rate is just 50 basis points more than the three-month Euribor rate, which is in negative territory right now. The loans are basically interest-free. At a 2% discount rate, the present value of the repayments would be about €40 billion.

The EFSF loans, too, are practically interest-free, with repayments spread over 32 years, starting in 2023.

Most countries would need to issue new debt to cover the guarantees, a whopping €130.9 billion exposure, but in present value terms, it amounts to less than €100 billion. Besides, the guarantees are already accounted for in the European countries’ debt levels.

The only payments Europeans should worry about now are the ones due on bonds owned by the ECB. The total amount Greece owes is €27.2 billion, with €4.4 billion coming due in July and August 2015, and most of the rest scheduled to be repaid in 2017 and 2019.

If Greece defaults, however, the ECB probably won’t even need to make any capital calls on euro countries’ central banks.

In total, the potential losses from a massive Greek default appear to outweigh the pain of investing another €53.5 billion over the next three years. Not counting the ECB and Target2 exposures, Europe would be looking at a present-value loss of €140 billion.

If it behaves like a bank, Europe would be tempted to lend more money to help Greece get back on its feet and repay the huge debt.

The problem, however, is that Greece also wants debt restructuring, ideally a write-off, and it has plenty of backers, including the International Monetary Fund, which considers the current burden unsustainable. It’s anybody’s guess how the forgiveness might be structured, but if half of the existing debt’s present value is snipped off, the decision for the EU-as-bank becomes trickier.

What if Greece is still unable to start paying off the old loans after a few years, and the third bailout is just added to the mountain of debt that can never be honoured? It would become a matter of trust between lender and borrower.

The banker would be tempted to offer partial debt relief, but no further loans. Why throw good money after bad? For the bank’s shareholders — in this case, EU countries — it would also be easier to accept a sunk cost than to justify fresh spending.

It’s difficult to say, however, how much such a solution might help Greece, given that most of the debt in question is backloaded and isn’t a burden for the Greek government today. If it is just a debtor, not a sovereign, it would be tempted simply to default on all its debts and start from scratch.

So it’s conceivable that a bank would approve the new loan just to avoid immediate write-offs. Given all the political implications of a Greek euro exit, or Grexit, and European politicians’ crisis fatigue, such an outcome is the likeliest, too.

As with a loss-averse bank, however, the day of reckoning will eventually come. It’s hard to believe that the government of Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, which has accepted the creditors’ austerity demands to secure more money, will be good at implementing a programme so far removed from the one with which it came to power, and that Greeks will have much patience for it.

It may be possible to avoid disaster for a year or two, but there is a better case for Grexit than the one Tsipras makes for an extension of the country’s self-torture. — Bloomberg View

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg View columnist.

This article first appeared in The Edge Financial Daily, on July 13, 2015.