This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on January 21, 2019 - January 27, 2019

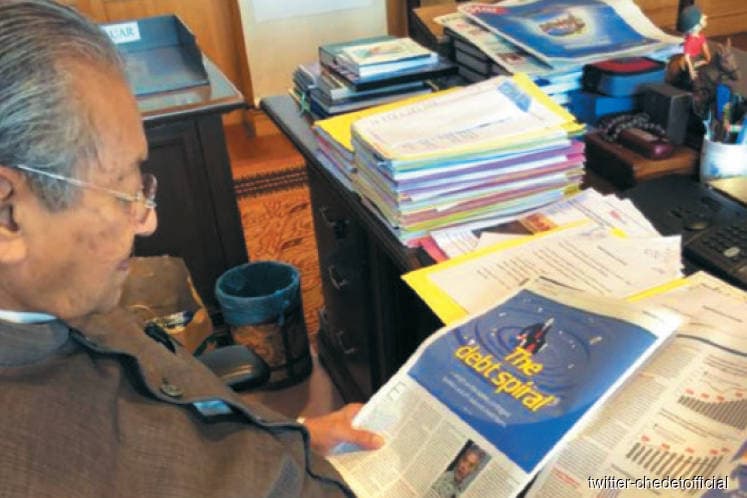

WHEN Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad voiced his sadness and disappointment on social media a year ago over how the country’s debt had ballooned close to RM1 trillion, not many would have thought the nonagenarian would be prime minister again today and have a committee tasked with reducing Malaysia’s debt and liabilities to a “manageable” level within 18 months.

It is understood that any proposal from the committee “should promote and not retard economic growth”. It would also “promote the deepening of financial markets, so the impact on financial markets should be positive”, a source says. Any action plan to lower the country’s debt and liabilities should also not disrupt the government’s delivery system.

The Jan 15 statement from the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), issued just before Dr Mahathir went on a working trip to Dakar, Senegal and Oxford University in the UK, does not define what a manageable level for Malaysia’s debt and liabilities is.

The size of debt and liabilities to be managed is also not known nor whether the committee will be accorded special statutory powers to facilitate corporate restructuring similar to those of the Corporate Debt Restructuring Committee and Pengurusan Danaharta Nasional Bhd, which were set up in 1998 following the Asian financial crisis. The committee’s targets and financing requirements, if any, have also not been spelt out.

It is not known whether the monetisation of government assets as well as the restructuring of entities like 1Malaysia Development Bhd (1MDB), Lembaga Tabung Haji, FELDA and the National Higher Education Fund (PTPTN) would also come under the committee. PTPTN, which has just over RM40 billion of government-guaranteed debt, for example, is an agency under the Ministry of Education while Urusharta Jamaah Sdn Bhd, which took over RM19.9 billion of Tabung Haji’s underperforming assets at book value, is a special-purpose vehicle under the Ministry of Finance.

The PMO’s statement does say, though, that the five debt and liability management committee members “are experts in finance, economics and law” and “will report directly to the prime minister”.

Apart from Treasury secretary-general Datuk Ahmad Badri Mohd Zahir and the Attorney-General’s Chambers head of advisory division, To’ Puan Azian Mohd Aziz, the other three members are economic adviser to the prime minister Dr Muhammed Abdul Khalid, Bank Negara Malaysia board member Gooi Hoe Soon and Securities Commission Malaysia board member Ahmad Faris Rabidin. Gooi and Faris are not officials of the regulators.

Faris, who is also a member of the 1MDB committee formed by the Council of Eminent Persons, was formerly a financial sector expert with the Asian Development Bank, and had provided advisory work to Indonesia’s financial services authority. Gooi has more than 35 years’ experience in accounting and corporate finance.

It is understood that the committee reports to the prime minister because the debt and liabilities to be reduced extend beyond companies under the MoF.

“I think it’s a good initiative by the government, which reaffirms its commitment to debt consolidation and improving the country’s fiscal strength. [That] the committee reports directly to the prime minister reflects the priority of the matter,” says Julia Goh, senior economist at UOB Bank Malaysia.

“A stable benchmark for debt-to-GDP for developing countries is around 40%,” she says, citing work done by the International Monetary Fund. She adds that some countries with similar sovereign scores and ratings as Malaysia have debt-to-GDP levels of less than 30%.

“To reduce Malaysia’s debt to such a benchmark level in 18 months is a tall order. It could also be disruptive and come at the expense of growth and stability. So the committee should set a realistic target that does not compromise other areas of the economy,” Goh says, stressing the importance of ensuring efficient execution and the need to keep up the pace of reforms.

Suhaimi Ilias, group chief economist at Maybank Investment Bank, reckons that the committee’s attention would be more on contingent liabilities arising from government-guaranteed debt, which has risen significantly in recent years, mainly due to the financing of major infrastructure projects.

“As we understand it, there is the implicit target of keeping on-balance-sheet government debt and government-guaranteed debt at no more than 70% of GDP, and as at Sept 30, 2018, we were at the threshold of 69%,” he says, adding that rating agencies and fixed-income investors have focused on on-balance-sheet and government-guaranteed debts, which are, overall, within the self-imposed limits and thus “manageable”.

That said, rating agencies such as Moody’s Investors Service have noted that Malaysia’s debt affordability “remains weak” with the share of revenue-to-GDP of 16.3% last year likely to remain low or near a record low.

When affirming Malaysia’s rating recently, Moody’s said the country’s “high debt burden is a significant constraint on the rating” and that federal government debt-to-GDP of 50.7% in 2017 was “significantly higher than the median of 39.7% for A-rated sovereigns”.

According to the 2019 Economic Outlook report, the federal government’s debt and liabilities stood at RM1.07 trillion or 74.5% of GDP as at June 30, 2018 — RM725.2 billion official national debt (50.7% of GDP), RM184.9 billion of other liabilities (12.9% of GDP), RM117.5 billion committed government guarantees (8.2% of GDP) and RM38.3 billion net debt of 1MDB (2.7% of GDP).

As at Sept 30, 2018, Malaysia’s official federal government debt stood at RM731.13 billion or 51.1% of GDP while debt guaranteed by the federal government stood at RM258.86 billion (RM258.392 billion as at June 30, 2018), bringing the total to RM990 billion or about 69% of GDP, Bank Negara Malaysia data shows. The latter excludes broader debt and liabilities, which potentially add at least another 10% of GDP to debt.

“As the government has asserted that liabilities from 1MDB will be resolved and involve budget transfers, we include 1MDB’s debt in our estimate of total government debt. We expect Malaysia’s debt burden to rise to 52.8% of GDP in 2018 and to remain relatively stable after,” Moody’s writes in a Jan 7 note.

Moody’s also noted how Malaysia’s interest payments account for 13.1% of revenue, “significantly higher than the A-rated median of 4.7%”.

Malaysia’s debt service charges are projected to rise to RM33 billion this year from RM30.88 billion (13.1% of federal government revenue) last year. This sum is 12.9% of headline federal government revenue. Excluding the RM30 billion special dividend from Petronas, debt servicing charges would be about 14.2% of government revenue this year — the highest since 2000 and just below the 15% administrative threshold for debt servicing charges. The ratio of debt servicing charges to normalised operating expenditure (excluding RM37 billion of tax refunds) is even higher, at 14.8%, for this year.

Reducing the ratio of debt servicing charges to revenue as well as operating expenditure would go a long way towards making the country’s debt more manageable. Dr Mahathir had previously told reporters that “just repaying the interest can bankrupt us, what more the principal sum”, when talking about the RM1 trillion debt burden inherited by the current government in May last year.

In an interview with The Edge in June last year, Dr Mahathir said he had no debt, had never borrowed from the bank or owned shares on the stock market. “When I ran the government, one thing that concerned me was, do we have the money? Can we do this? And if you manage it well, you can do it. We built the North-South Expressway, we built the double-tracking (railway line), we built new ports, airports … all these things were built with very little borrowed money.”

To be sure, the renegotiation, retendering and postponement of large infrastructure contracts are already under way to contain the government’s debt levels, economists say. Tightened procurement practices and open tenders also prevent leakages in revenue.

Economists expect the restructuring of entities and statutory bodies with government-guaranteed debt and the monetisation of the government’s assets to be given priority.

The government has said there will not be any fire sale of assets as that is not in the best interest of the people or the country’s finances. Some experts contacted, however, would like the government to provide an indication of potential asset monetisation and a timeline of how that could help pare down the country’s debt burden without sacrificing economic growth.

“A key question is how much can be expected from 1MDB-related recoveries. Is it possible and realistic to get back US$7.5 billion from Goldman Sachs?” asks Suhaimi, referring to the sum the Malaysian government is suing the investment bank for.

He is not the only party looking for steady information flow on Malaysia’s progress in dealing with its debt and liabilities. Whatever the committee’s role may be, the government, he says, needs to make sure that it can deliver the guided fiscal consolidation over the next three years, underpinned by a sustainable and diversified revenue base.

UOB’s Goh concurs, noting that the 18-month deadline for the committee falls within the three years that Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng said were needed to regain greater fiscal flexibility. It also paves the way for the planned move from cash accounting to accrual accounting by 2021, which, experts say, should provide a more accurate picture of the risks associated with the government’s contingent and future liabilities.

The committee’s 18-month deadline to the middle of 2020 is also close to the two years that Dr Mahathir estimates he will hold office. A good prognosis of Malaysia’s financial health would be a gift for the whole country as he turns 95 on July 10 next year.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.