This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 5, 2018 - March 11, 2018

NO one person or country is perfect. Our neighbour, Singapore, too has its own woes and … fines. When it comes to fiscal discipline, however, Malaysia has much to learn from the city state.

It is easy to dismiss Singapore — with a land mass of 721.5 sq km and population of 5.6 million — as a much easier place to govern. By comparison, Penang island is 299 sq km and has a population of about 750,000. Including Seberang Perai, the state has a land mass that is 45% larger than Singapore’s but a population of only 1.75 million or just under a third of the city state’s. The latter means that Singapore needs to be highly efficient and creative when it comes to land use and future-proofing its economy to remain a respected and highly developed independent nation.

Unlike Malaysia, which is blessed with an abundance of natural resources, Singapore has very good reason to be kiasu and kiasi — the colloquial speak for being afraid of losing out (overly competitive) and being afraid of doing something wrong (premature death).

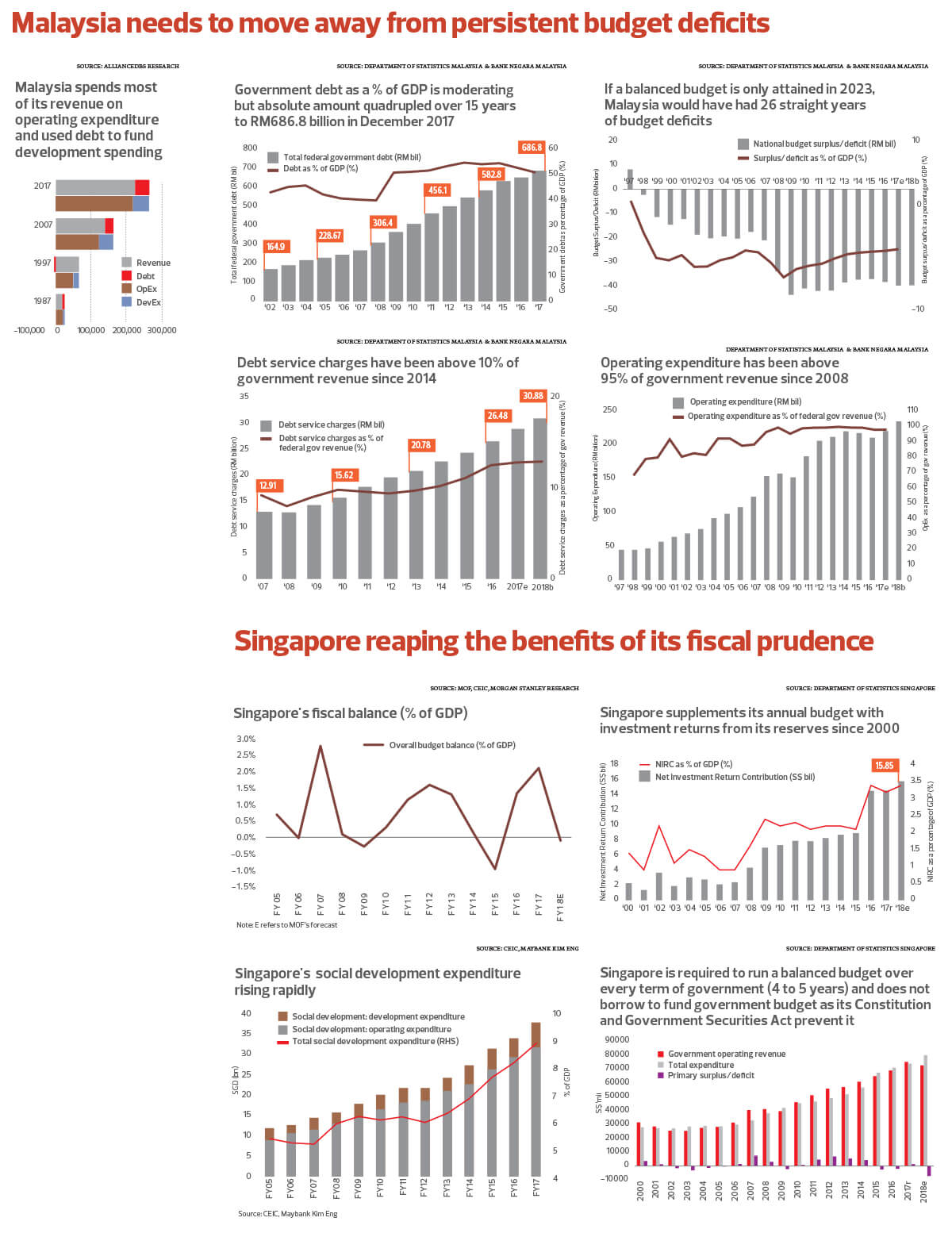

Singapore, which separated from Malaysia in August 1965 and still buys water from our country, achieved self-reliance in water in 2016 even as supply in several states here was hit by drought. And even as Malaysia racked up debt of over RM687 billion by spending more than we earn — during both the good times and the tough times the past two decades — Singapore prudently accumulated reserves from its budget surpluses as well as its ability to invest and grow its war chest (a secret number of over S$1 trillion [RM2.96 trillion]).

Singapore’s annual budget began enjoying what it calls a Net Investment Return Contribution (NIRC) from 2000, government data shows. Apart from up to 50% of net investment returns from GIC Pte Ltd, Temasek Holdings Pte Ltd and the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), Singapore’s NIRC also comprises up to 50% of net investment income from past reserves and remaining net assets.

What was a mere S$2.29 billion (1.4% of gross domestic product) at the turn of the millennium grew to S$7.35 billion (2.2% of GDP) in 2010 and reached S$14.61 billion last year.

Now the largest contributor to Singapore’s budget, the NIRC is expected to reach a new all-time high of S$15.85 billion or 3.4% of GDP this year, which covers nearly 20% of government expenditure.

“Singapore has self-imposed strict fiscal rules to prevent the government from spending beyond its means,” says Chua Hak Bin, senior economist at Maybank Kim Eng Research.

“First, the Singapore government cannot run a fiscal deficit (it must be balanced or surplus) over each term of government (within each electoral cycle). Second, Singapore sets aside all land sales into reserves, which are then invested to generate future returns. For FY2017, land sales amounted to S$12.9 billion, a considerable sum,” he adds, relating how proceeds from land sales in Hong Kong flow directly into budget revenue and are spent.

“Third, only up to half of the net investment return from reserves (with GIC, Temasek and MAS) can be drawn upon for the budget. The rest will be ploughed back into reserves and reinvested,” says Chua, who reckons that Malaysia “will be hard-pressed to adhere to a balanced budget rule, given rising spending needs and sensitivity of fiscal revenue to energy prices” despite a broadened revenue base.

Singapore had tapped on past reserves (US$4.5 billion during the 2008 global financial crisis) but special permission from the president — not the prime minister — is necessary. The government also does not borrow to fund its annual budget and has no net debt, according to data on its Ministry of Finance’s website.

“[Malaysia] ran a budget deficit for the last 20 years, hence the lack of reserves for investment to have an NIRC … The amount contributed by Khazanah [Nasional Bhd] in terms of dividend is relatively small by comparison,” another seasoned economist surmises.

Khazanah paid RM500 million in dividend in 2016 and RM1 billion last year while Bank Negara Malaysia paid RM3 billion in dividend in 2016 and RM2.5 billion last year, official data shows. National oil company Petroliam Nasional Bhd (Petronas) paid RM16 billion in 2016 and 2017 and has committed to pay RM19 billion this year.

“A strategic case can be made that some proportion of Petronas’ dividends should be set aside and accumulated in a sovereign wealth fund, which is to be invested in external assets. Recycling Malaysia’s oil profits and reserves into more oil and gas and domestic assets only concentrates the investment risk on Malaysia’s economic cycle, oil prices and the ringgit [and the] purpose of setting reserves aside is so that the government can tap on these funds when there is a sharp economic downturn, which often coincides with a collapse in the ringgit or oil prices,” says Chua.

“The ideal type of fiscal reserves should, therefore, not be correlated with Malaysia’s economic or stock market cycle, oil prices or the ringgit. It is an insurance against a crisis.”

As it is, dividends from Petronas, Bank Negara and Khazanah form part of the interest and returns on investment under the federal government’s non-tax revenue but their contributions pale in comparison with debt service charges of RM26.48 billion in 2016, RM28.87 billion in 2017 and the RM30.88 billion expected for 2018.

“While the Malaysian government has committed to fiscal discipline and the progressive reduction in fiscal deficit, there is a general lack of political will to bring its high operating expenditure down to a more manageable level. A bloated civil servant population, high expenditure on their remunerations and a pension scheme that is unsustainable are examples. While efforts have been made to cut subsidies, it appears to have found its way back gradually to the government budget,” the seasoned economist laments.

How can the government budget better?

“[Malaysia needs to] contain the civil servant population, focus on the productivity and efficiency of government services, restructure the pension scheme to one that is self-sustaining, implement a transparent open tender system of awarding government contracts and optimise government revenue by removing duplicating incentives (that would also cut down abuses),” says the seasoned economist.

While Singapore’s decision to raise the Goods and Services Tax (GST) by 2% to 9% by 2021 would provide Malaysia with headroom to move its 6% rate higher, economists reckon that the government still needs to manage its finances better by bringing down operating expenditure and leaving room for more development spending (without relying on debt) to grow the economy.

“The ability to bring about higher labour productivity and income for the population that translates into higher standards of living is important. Otherwise, the rising cost of living would be a real constraint on the low to middle-income groups … The other factor to consider is the ability to bring profiteering of traders under better control so that it does not spill over into higher inflation unnecessarily,” the economist says.

That’s important given that our government “may have to plan and prepare for growing liabilities from public-sector pensions and healthcare spending from an ageing demographic (which fortunately, comes at a later time for Malaysia versus Singapore or Thailand), as the existing fiscal revenue sources will likely not be sufficient”, says Chua, who reckons that the Malaysian government “may have to look into future and new revenue sources to finance these needs”.

He believes that Malaysia “may want to see how it can consolidate and reduce the number of exemptions within the GST framework first [as well as on e-commerce goods and imported services] before raising the GST. Otherwise, consumers will be even more tempted to switch to internet shopping to escape the GST net”.

Noting that Singapore has been introducing more “wealth taxes” on property and personal income to make the overall system more progressive and to fund social transfers to the lower income group, Chua reckons that Malaysia may also want to make the property tax system “more progressive” to bolster its revenue options or sell land to bolster its reserves.

“Land is, however, also a state matter and often the main revenue source for some states. Rights over the proceeds from land sales may, therefore, not be as straightforward as Singapore’s case.

“Singapore’s strong fiscal standing has earned the government an AAA credit rating (which is shrinking in terms of the number of qualified countries) and strengthened the Singapore dollar over the years. Strengthening Malaysia’s fiscal and savings discipline would also raise Malaysia’s credit standing and the ringgit’s longer-term resilience,” says Chua.

Malaysia’s self-imposed 55% debt-to-GDP ceiling and zero deficit targets will lead to some discipline but he reckons “further fiscal discipline might be necessary to keep government guarantees and borrowings via government-linked entities in check”.

Building a case for the future

“The Malaysian government has made significant progress so far in the rationalisation of its expenditure. Further efforts in rationalising expenditure would be helpful, such as making subsidies more targeted, right-sizing the civil service and improving healthcare, education and transport service cost recovery,” says AMRO (Asean + 3 Macroeconomic Research Office) chief economist Khor Hoe Ee, who notes how Singapore’s government has managed to anticipate the large increases in the coming years and “has the resources to tackle the challenge” of ageing and technological changes.

“The past few [Singapore] budgets in particular have put great emphasis on ageing-related spending, with more financial support for senior citizens, such as the Silver Support Scheme and the Pioneer Generation Package. They have also provided all residents with Medishield Life with universal coverage … In terms of labour shortage due to the ageing population, the government is also looking for ways to reduce manpower demand, while enabling older workers to continue to contribute to the society meaningfully … In the past few years, each of Singapore’s annual budgets was built on the previous budgets to embrace technological changes,” Khor adds.

It would seem that a bit more kiasuism may be necessary this side of the Causeway. Freedom from a persistent budget deficit would allow Malaysia’s attention to move further, beyond covering operating expenses and immediate needs to focus more on catering for impending structural changes and the future needs of the people and the economy.

Click / Tap image to enlarge

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.