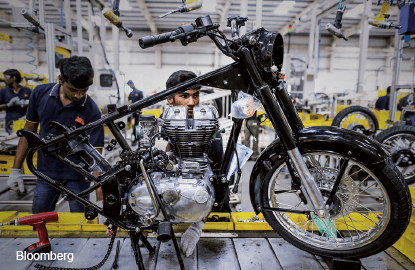

IN a sweltering factory in southern India, Royal Enfield motorcycles are being painted and lacquered by giant robotic arms that move at twice the maximum speed of a human limb, day in, day out, never making a mistake.

Only a few workers are still needed on the paint line at Royal Enfield Motors Ltd’s plant in Oragadam, doing touch-ups on the iconic two-wheelers coveted for their classic design. Four robots can do the work of 15 human painters toiling across three shifts.

Robots and automation are invigorating once-sleepy Indian factories, boosting productivity by carrying out low-skill tasks more efficiently. While in theory, improved output is good for economic growth, the trend is creating a headache for Prime Minister Narendra Modi: Robots are diminishing roles for unskilled labourers that he wants to put to work as part of his Make in India campaign aimed at creating jobs for the poor.

India’s largely uneducated labour force and broken educational system aren’t ready for the more complex jobs that workers need when their low-skilled roles are taken over by machines. Meanwhile, nations employing robots more quickly, such as China, are becoming even more competitive.

“The need for unskilled labour is beginning to diminish,” Akhilesh Tilotia, head of thematic research at Kotak Institutional Equities in Mumbai and author of a book on India’s demographic impact. “Whatever education we’re putting in and whatever skill development we’re potentially trying to put out — does it match where the industry will potentially be five to 10 years hence? That linkage is reasonably broken in India.”

Competing tasks

Improving automation will “likely compete with some low-skill tasks”, Standard Chartered plc economists in London and Toronto wrote in a May report.

Royal Enfield’s plant, near Chennai, is an example. Spray painting is a repetitive and hazardous job, perfect for a machine.

Humans are imperfect: They miss spots, which can corrode the bikes. They waste more because they go over the same place twice. No human can paint exactly the same way each time.

Robots installed by Zurich-based ABB Ltd at Royal Enfield’s newest plant in southern Tamil Nadu state have 2.1m mechanical arms that reduce paint wastage by half. At maximum speed, they paint four times faster. They never miss a spot, never take a break, never go on strike.

Nimble production

Robots also mean more nimble production in an era of frequent product launches and shorter manufacturing cycles: While a human needs to be retrained, a robot can switch at a touch of a button.

“Large manufacturing plants can really struggle to find enough stable, skilled blue-collar workers that can do repetitive tasks day in, day out,” said Per Vegard Nerseth, ABB’s global head of robotics. “Turnover is very high, so you have a huge task training people, which incurs costs. That makes the payback for robots more favourable for a company.”

The Oragadam plant started with four painting robots in 2013, and plans to add 14 more as it expands. Both Royal Enfield and ABB declined to disclose the cost of the machines, but said the investment would pay for itself in about two years.

Royal Enfield’s older plant further north has also recently added four welding robots, which do in 20 seconds what takes two minutes for a human. The company declined to say how many workers were displaced or whether it had further automation plans for the facility in Tiruvottiyur.

New jobs

While displacing some types of jobs, robots also create new ones, like engineers to maintain and programme them. A study by industrial analysis firm Metra Martech Ltd shows they help create more jobs than they eliminate from the assembly line.

India can use the help. Labour productivity of Indian factories is the worst among major economies, according to a report by the Boston Consulting Group and the Confederation of Indian Industry.

Robot installations in India grew 23% in 2013 from the previous year, with annual sales hitting a record 1,900, the latest figures available from the International Federation of Robotics (IFR). That’s just a fraction of China. About 56,000 units were sold last year alone in the world’s biggest robot market, where factories including iPhone producer Foxconn Technology Group are helping China keep its manufacturing edge against lower-wage rivals.

It’s not just factory jobs either. In Meerut, about 80km north-east of the capital Delhi, local police are considering using robots to help guide traffic at busy intersections, Ramit Sharma, the city’s deputy inspector general, said by phone on Monday. Information technology companies and banks are also looking to automation to eliminate lower-end jobs and clerical staff, according to a June report by Kotak.

Losing out

Still, robots have barely penetrated India and China relative to the size of their labour forces. Rather, Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia lead developing Asian nations in robot density — the number of industrial robots for every 10,000 manufacturing workers, according to IFR data.

“There’s the threat of India losing out,” said Madhur Jha, senior economist at Standard Chartered in London. “Other countries are slightly more developed, have a stronger manufacturing base, and are moving towards automation more quickly to keep themselves competitive.”

When Modi announced his Make in India campaign in September, he cited India’s “greatest strength” as having 65% of the population under 35. That demographic dividend may not pay out as expected.

For one, India’s working-age population is increasing far faster than the number of jobs in the formal sector: roughly one million a month versus one million a year, according to a report by JustJobs Network, a labour research institute.

Stealing jobs

It’s also not clear if factories planned today will create the number and type of jobs that Modi is expecting.

“If you build a factory today assuming that it will create 100 jobs, in the course of 10 years as new technologies are adopted, it may create only 10% or 20% of the jobs you expected,” said Makoto Yokoyama, head of Mitsubishi Electric Corp’s factory automation division in India.

“It’d be a lie to say that robots won’t steal jobs,” said Sonali Kulkarni, who heads the India unit of Fanuc Corp, one of the world’s biggest robot makers. “They will, but not the jobs that people should be aspiring to. People are capable of really a lot more than mindlessly loading or unloading from a machine or welding.”

Yet, India is failing to educate its illiterate 287 million to do much more than that.

Unemployable grads

The average Indian adult has been schooled for only 4.4 years, the worst among Asia’s major developing economies, according to United Nations data. Worse, half of the five million graduating annually with bachelor’s degrees are unemployable because of poor cognitive and language skills, according to a study by Aspiring Minds, a skill-assessment company. Larsen & Toubro Ltd, India’s biggest engineering firm, is forced to train new hires from scratch.

“The challenge for many emerging markets, like India, will not be to create low-cost jobs, but to make use of their gigantic human potential through broader and better education,” said Antoine van Agtmael, a former World Bank economist.

In the race to create factory jobs, Modi isn’t just competing against Asian rivals. Robots are increasingly helping developed economies. In Switzerland, robots make toothbrushes for export; in Spain, they cut and pack lettuce heads; in Germany, they fill tubs of ice cream; and in the United Kingdom, they assemble yogurt into multipacks at a rate of 80 a minute.

Tharman Shanmugaratnam, chairman of the International Monetary Fund’s policy advisory committee until March and Singapore’s finance minister, gives India — and rivals such as Thailand, Vietnam and Malaysia — a fast-closing window to catch up with rich countries or miss the boat.

“Time is not on India’s side,” he told Indian policymakers at a government conference in December. “I give 10 years for labour-intensive manufacturing to survive in its present form before machines take over.” — Bloomberg

This article first appeared in digitaledge Daily, on August 14, 2015.