This article first appeared in Enterprise, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on June 12, 2017 - June 18, 2017

Residing abroad, alone, can be isolating — especially if it is the first time one has left the proverbial nest. Yearning for something familiar, Maryam Samirah Shamsuddin took to the library to browse through books and pictures that reminded her of home. It was then that she fell in love and began a lifelong affair with batik.

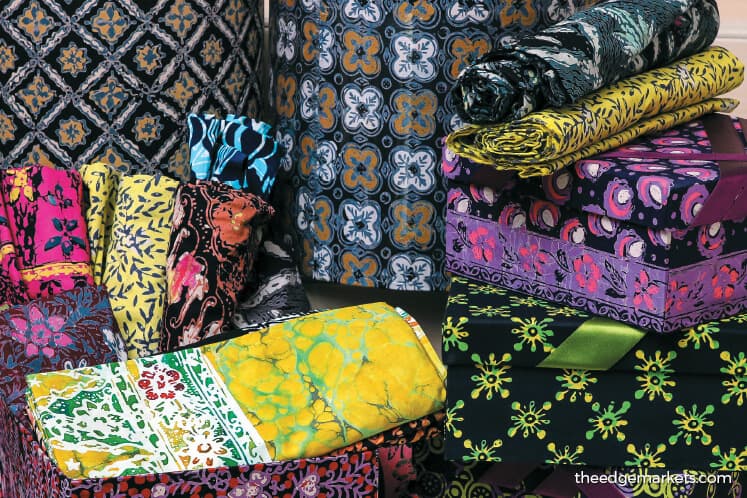

She made it a point to start buying both hand-drawn and block batik when she returned home for the summer holidays. “I started to buy batik whenever I could fly home and amassed quite a collection in two years,” she says.

After completing her A-Levels, she won a place at the University of Manchester to study architecture. But studying architecture and collecting more batik pieces were not to be because of the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis.

“When the pound sterling doubled in value against the ringgit, Mara called everyone home. But I was stubborn and chose to stay and pay for my tuition although it was very difficult,” says Maryam.

“I had to switch from architecture to accounting and finance — a less expensive course. Still, I had to juggle five jobs and negotiate the payment of my fees at the treasury every week.

“A year later, I suffered a haemorrhage and was hospitalised as my body could not take it anymore. After that, I wrote to several banks and foundations to ask for scholarships and grants. I was lucky that some of them offered me grants and I was able to graduate.”

Rekindling her love of batik

After returning home, Maryam worked at a consultancy for five years. “There, I noticed a trend of youngsters going into the retail business, although at the time, it was hard for them as the barriers to entry were high. So, I created a pop-up bazaar called Bijou Bazaar. It became this pop culture thing, along with the small retail brands we featured such as Mimpi Kita,

Old Blossom Box and Sugar Scarf, which kicked off their ventures at our bazaar.”

After a successful couple of years, she left her day job and Bijoux Bazaar to help her sister run a petrol station. “I helped my sister run her Petron petrol station in Saujana Impian, Kajang, for about two years. It was a monotonous and not a very demanding job. Thus, I started looking at batik websites again,” says Maryam.

“Then, I stumbled upon a website on batik, particularly block batik, by Susan Bylander, who is an art lecturer from Portland, the US. She told stories about 30 block batik artisans in Terengganu and catalogued their work extensively. For the longest time, hers was my go-to website on block batik and its history.”

And then out of the blue, in 2012, Bylander’s website became inactive. “I was shocked and puzzled. I also became restless because I had lost a crucial source of information,” says Maryam.

“So, I went to Terengganu to look for the artisans to satisfy my curiosity. There, I learnt that there were fewer than 10 block batik artisans in the state as the commercialisation of batik centred on hand-drawn batik as it commands higher profit margins.”

She also learnt that the equipment used to make block batik was expensive. “To make a block batik sarong, six block designs are used. These six blocks are considered a set. The sets would set you back more than RM1,000. Of course, more intricate designs push the cost up further. Meanwhile, the equipment used for hand-drawn batik only costs RM18.

“Now, there are only seven batik artisans and one batik block maker left — Pok Ya. In the 1990s, there were 300 artisans (including block makers) in Terengganu.”

Maryam managed to contact Bylander, who is in her sixties. “She wants to donate her collection of block batik to Malaysia. Her collection is valuable as the batik was made by both active and retired artisans. She is very knowledgeable about Terengganu block batik. She knows each artisan’s signature design and can explain its uniqueness.

“She used to come to Malaysia every summer. In 2012, she stopped coming here and did not update her website because she said we were killing our own culture. That year, the state government had relocated the block batik artisans to a flat as it wanted to develop the area where the artisans originally resided. Little did they know that the size of the flat would restrict the artisans from practising their craft.”

Dying art

Batik refers to cloth on which wax has been applied to ensure clear separation of colour upon dyeing of the fabric. “Either you draw or stamp the wax onto the fabric. In terms of the wax, new mixtures are now being used. They are far lighter than they used to be. Batik lukis, or hand-drawn batik, is more popular as it is easier to design and make compared with block batik, which is more expensive and time-consuming,” says Maryam.

Pok Ya, the sole batik block maker in Terengganu, suffered a stroke recently, so there is a real threat of losing the art of designing and making batik blocks. His son, who is an artisan himself, knows how to make these blocks. However, he has scaled back his production as he does not make enough money from this trade to survive,” says Maryam.

“I believe they are not exposed to the possibilities of other applications for block batik. Rather than just focus on clothing, they could work with interior designers to produce wall art or upholstery,” she adds.

Maryam is grateful that despite all the hindrances, Pok Ya is still practising his craft. “He operates from a small flat. Due to the lack of space, he can only make batik blocks now and has stopped creating batik pieces.”

She says these block batik artisans are struggling and most of them had to give up their trade as the cost and effort to produce a piece as well as the design of the blocks did not commensurate with what they earned. “I do not know what they earned previously. But in the last 10 years, the price of block batik has been static, due to the wholesalers who insist that it remains at RM16 to RM18 apiece.”

Maryam believes that the price is too low because good quality block batik pieces from Indonesia command about RM80 each. “However, the local artisans thought that if they sold their pieces at that price, no wholesaler or customer would buy it,” she says.

“So, I started Cotton & Sago in 2015 to prove to them that they can sell their batik at a higher price point. I bought their pieces at RM20 each and sold them for double the price. After each sale, I sent them a picture or screenshot of the transaction.”

However, Maryam points out that her website is not a proper online store and transactions are done in real life, rather than virtually. “I participated in pop-up bazaars, such as Arts for Grabs, to introduce block batik to the market. I was lucky that I found an advocate in Pang Khee Teik — the founder of the pop-up bazaar.

“His social media posts on our block batik drove traffic to our website. That was when our offline transactions grew by leaps and bounds.”

After proving to the local artisans that their batik could indeed sell at higher prices, Maryam started purchasing batik blocks for RM22. “We stopped at RM22 because the artisans were being pressured not to increase the price any further. So now, the focus of Cotton & Sago is to increase sales.”

Now, most of its business comes from corporate sales, custom orders and soft furnishing supplies. So, while there are significant business-to-customer transactions, the business-to-business model dominates.

Maryam chose the name Cotton & Sago because it reminded her of her first visit to a batik workshop in Terengganu. “When I arrived there, I noticed that there was a keropok lekor shop near the batik workshop. Cotton is the fabric commonly used for batik and sago flour is the binding agent for keropok lekor. So, the name is a point of reference to how it first started and how far we have come.”

Currently, Cotton & Sago only sells Terengganu block batik. “Batik Terengganu is popular, but it is not available in Kuala Lumpur. So, besides selling these pieces online, we also supply to various boutiques and pop-up kiosks,” says Maryam.

“Batik Terengganu uses higher quality fabric or material. The artisans also use Remazol, a synthetic dye, which is much safer than the most common dye used, Naphtol, which is carcinogenic. Naphtol is used to make Indonesian batik. If you wear batik dyed with Naphtol, the chemicals could be transferred to your skin and …”

Hence, it is of utmost importance to know who your artisans are and what chemical dye they use, she says. “When buying Indonesian batik, I only get those made with natural dye.”

Impact of Cotton & Sago

Maryam says the Terengganu artisans’ lives have improved, but not by much. So, she may need to expand her team to make a greater impact on their lives.

“The business model has changed, definitely. At first, the intention was to preserve the art of block batik and block making. Then, I realised that it needed to be financially sustainable to keep the industry afloat. It is not just about problem solving but also taking care of your ecosystem,” she says.

As social impact is a part of Cotton & Sago’s DNA, Maryam’s brother-in-law’s sister, who is active in social enterprise Biji-biji Initiative, encouraged her to seek the support of Malaysian Global Innovation & Creativity Centre (MaGIC).

“So, I applied for the accelerator programme and two weeks later, I received a phone call from MaGIC, inviting me to pitch my company. After the pitch, I enrolled in its accelerator programme from April to August last year.

“The programme is intensive. It covers the basics of what a social enterprise is, how to measure impact, how to run the business and what tools to use. At the same time, it gave us a sales target, asking us to set the number ourselves. My partner at the time and I gave ourselves a target of RM70,000. We went all out and made RM200,000!”

Since then, the company’s quarterly revenue has consistently hit RM200,000. Now, Maryam has set an annual growth target of at least 10%.

She says each social enterprise is different and has different ways to measure impact. For her, it is about improving the quality of life for the artisans and securing the future of the art of block batik. “We are supposed to get a third party to audit the company, but have not done that yet.”

Cotton & Sago is currently working with public universities, such as Universiti Teknologi Mara and Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, on an academic paper on block batik and how to improve the artisans’ livelihood. The paper is more than just an academic exercise as it will also be used as a proposal to the government.

When it comes to cultural preservation, small entities tend to fall through the cracks as the government usually funnels assistance to the larger ones in the hope that it will trickle down to the smaller players, says Maryam. “But sometimes, this only works in theory.”

Future plans

As the current generation is interested in cultural preservation and revival, block batik is bang on-trend. Maryam says there has been positive interest from fashion magazines to document and promote this art form.

“When they heard about Cotton & Sago, they wanted to work with us to create awareness about block batik and document the whole process, from block making to the completion of the batik piece. They also wanted to arrange for stylists and fashion designers to work with us to create more modern designs of block batik. This is something we look forward to.”

Maryam wants Cotton & Sago to be a lifestyle brand, much like Liberty of London. “It started out as a fabric retailer but now it is a lifestyle brand. Liberty of London popularised British patterns and we would like to do the same for block batik.”

She says there is a huge global market opportunity for batik and not many Malaysians know that batik designs are popular in the US and Europe. “For example, 1.2 million yards of Indonesian batik is produced a month for the global market. Hopefully, we can follow Indonesia’s example soon.”

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.