This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on September 10, 2018 - September 16, 2018

TO gain a better understanding of how our elections have been conducted and the reforms that are needed to make them clean and fair, The Edge speaks to political analyst Wong Chin Huat. In Part 6 of an ongoing series based on his presentation to the Institutional Reforms Committee, he discusses the choices we must make to address weaknesses in the current system.

The Edge: In the previous part, you focused on what makes the first-past-the-post (FPTP) election system, which we use, susceptible to manipulation. What conditions do we need for FPTP to work in Malaysia?

Wong: For a start, it will need an impartial Election Commission and stricter control on malapportionment and gerrymandering. There must be integrity in voter registration and the upkeep of electoral rolls too. Free and fair access to the media, fair and transparent political funding and neutrality in administration are also necessary. Finally, there must be judicial independence and the right to observe the election process.

Is FPTP the most suitable system for Malaysia, if all these conditions are met?

Even in its best form, there are certain issues that FPTP may give rise to in a diverse country like Malaysia. Let us focus on three aspects of the FPTP to see whether it is compatible with Malaysia, then consider the alternatives.

FPTP and a two-party system

The two-party system in the UK is widely credited for at least two things. First, it facilitates alternation of single-party governments, making it possible for voters to hold the entire government responsible and fire every minister if they so wish.

This is not possible in countries with coalition governments, as some parties may simply be too pivotal to be excluded from power.

Second, the two main parties compete to hold the middle ground, so that the country’s social fabric and national interests will not be damaged when power changes hands.

Two large national parties

Political scientists have long observed that the FPTP system tends to produce two large parties.

First, as votes for the smaller parties are not translated into seats, in that sense, they are wasted as only two large parties will thrive. Secondly, in anticipation of the wasted votes, voters will focus their support on the two largest parties.

US political scientist Gary W Cox has developed a generic formula of strategic voting to explain such voting behaviour. In FPTP, the voters concentrate their support on the top two frontrunners, because votes for any other trailing candidates would be wasted.

Cox further offers four situations where strategic voting would not happen:

1. The election outcome is a foregone conclusion (as what would happen in parties’ strongholds), making it impossible to change the outcome with strategic voting.

2. The top two front runners are not known, hence voters cannot vote strategically.

3. The top two front runners are known but equally bad for the voter, hence the voters prefer to vote sincerely (or abstain).

4. Regardless of the front runners’ standing, the voters are long-term rational, so they support a trailing candidate to improve his/her prospect in the future.

To what extent did Malaysians employ strategic voting in the 14th general election?

The GE14 results suggest that strategic voting happened but only partially. By and large, voters concentrated their support on two parties in the constituencies, but in about 40% of the constituencies, the winners did not win a majority of the votes.

This can be due to one of the last three factors stated above: inability to identify the top two front runners, rejection of the top two front runners for being equally bad, and long-term rationality. If these factors disappear by the next election, we shall see a two-party contestation format in most of the constituencies.

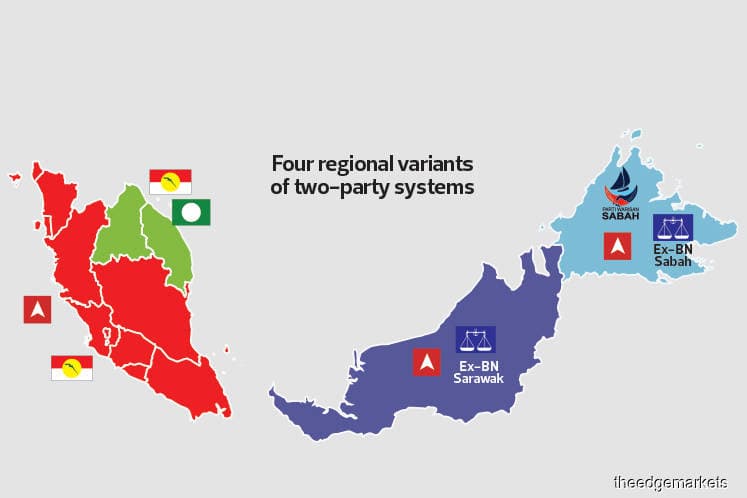

But there is not a two-party or two-coalition system as we understand it. The leading two parties (parliamentary seats on May 10 in parentheses) are different in four regions (see map):

1. Kelantan and Terengganu: PAS (15) v Umno (7)

2. The remaining states of West Malaysia: PH (98) v Umno (39)

3. Sarawak: Sarawak BN (19) v PH (10)

4. Sabah: Warisan + PH (14) v Sabah BN (11)

What are the implications of such strategic voting for Malaysia’s political coalitions?

In fact, BN may be fast disappearing as a national coalition. The fast disintegration of Sabah BN is telling — from an initial total of 29 state seats, it is reduced to Umno’s 11, with 12 state lawmakers from Umno (6), UPKO (5) and PBRS (1) switching sides to the Warisan-PH camp, and PBS, with its six lawmakers, going independent but remaining a partner of Sabah Umno.

The former Sarawak BN parties have now formed Gabungan Parti Sarawak. The earlier speculation was that Sabah Umno could merge with PBS to be a standalone local party. If that happens, BN will be reduced to a rump Umno in West Malaysia, with 46 parliamentarians and 132 state assemblypersons. MCA and MIC with three parliamentarians and two state lawmakers are insignificant.

What is likely to happen to BN and its allies, given this development?

Cox proposes that parties respond strategically to the degree of concentration of executive power in deciding whether to merge as a larger party. If the chief executive is highly concentrated, then parties would have to merge into only two blocs, so that they stand the chance to win power.

That is where Malaysia’s experience did not conform to the theory, which needs modification. Power had always been highly concentrated in Malaysia after 1969, and opposition parties were forced to form a coalition to take on BN, which resulted in the Gagasan Rakyat-Angkatan Perpaduan Ummah (GR-APU) in 1990, Barisan Alternatif (BA) in 1999 and Pakatan Rakyat (PR) after 2008. But all these coalitions disintegrated before or just after the next elections, and the commonality behind their disintegration was their electoral setback, making the prospect of them winning power dim, if not non-existent.

In the Malaysian context, the main opposition parties merge into the second coalition to take on the ruling bloc only when they see the prospect of coming into power.

So what forms of two-party competition could evolve?

It is possible and probable for PAS and Umno to converge in West Malaysia, and for Sabah and Sarawak BN component parties to form a single bloc. However, it is hard to imagine that BN component parties in Borneo would like to form a pact with PAS. As a matter of fact, there may not be enough prospect of future victory to keep Umno in West Malaysia with its Borneo allies, including Sabah Umno, in the same camp.

If PH would eventually face two separate coalitions, PAS-Umno in West Malaysia and a Borneo coalition in East Malaysia, how likely would they be able to put up benign competition against PH? This leads to the second question we should consider in assessing the British “two-party system”.

What is this second question?

This is the issue of centripetal competition, which concerns the tendency of parties to move towards the middle ground. The centripetal competition between the two main parties in UK suggests that voters would vote for the parties closest to their ideological position, and since most voters are concentrated in the middle, hence the parties need to move towards the centre. This is called the “median voter theorem”.

The “median voter theorem” is however based on a unipolar population where voters’ preferences show a bell curve distribution on a given ideological spectrum. For example, where they favour economic policy that leans to the left or right. But a unipolar society is what we do not have in Malaysia.

So, how would you characterise Malaysian voters?

Malaysia is by and large a bipolar society, where Malay-Muslims and the ethnic minorities tend to have very different views on free-market/meritocracy versus state-intervention/affirmative actions, or on separation of religion and state versus close ties between the two. A middle ground for the entire population — for example, a limited application of bumiputeraism — may be an unpopular radical position among both the Malay-Muslims and ethnic minorities.

Empirically, the emergence of a multi-ethnic opposition coalitions — GR-APU, BA or PR — did not result in lasting centripetal competition between them and BN. Instead, at least one side tended to move away from the centre. After 1990, while BN moved to woo the non-Malays with the inclusive Vision 2020, PAS moved to push for hudud punishments in Kelantan and Tengku Razaleigh’s Parti Semangat 46 added the word “Melayu” to its name to emphasise its Malay orientation.

After 1999, while BN played up Malay anxieties, PAS too moved to push for hudud implementation in Terengganu. After 2013, Umno moved further to the right and successfully broke up Pakatan Rakyat by enticing PAS with the implementation of some hudud punishments.

That does not look like a healthy trend, does it?

It would be naïve to expect the badly-damaged BN to quickly bounce back to compete with PH on moderation. The more likely development as we have said is its disintegrating into two blocs: Umno in West Malaysia, which may eventually converge with PAS, and a Borneo coalition in East Malaysia.

Deprived of the prospect of regaining federal power, what would hold them back from championing a more aggressive agenda of Malay supremacy and Islamisation or one of Borneo state rights that may eventually move on to self-determination?

There is no optimistic sign that we will see a benign two-party competition.

Next: Avoiding nasty two-party competition

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.