This article first appeared in The Edge Financial Daily on May 21, 2018

Since the late 1980s, in one way or another political Islam in Malaysia has been dominated Islamist party PAS, and Umno, the lynchpin of the Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition.

The decades-long contest over who is “more Islamic” — often to win votes — cemented the “conservative” stance in many areas and eventually inched into religious policing and extremism.

But with both PAS and Umno on the back foot following the unprecedented defeat of BN Pakatan Harapan in the 14th general election (GE14), is the status quo finally ripe for change?

Certain signs point to it.

Amanah, one of the four parties in the Pakatan coalition, is expected to fill the vacuum.

The breakaway faction of PAS is a torchbearer of the inclusive “Islam for All” approach that it says PAS has abandoned under the leadership of Datuk Seri Abdul Hadi Awang. In a nutshell, Amanah advocates an “objective-based” approach to Islam in the modern setting. As part of the administration, its status as the new face of “mainstream Islam” will be put to the test as Muslim-majority, multi-ethnic Malaysia goes through its first change of government in 61 years.

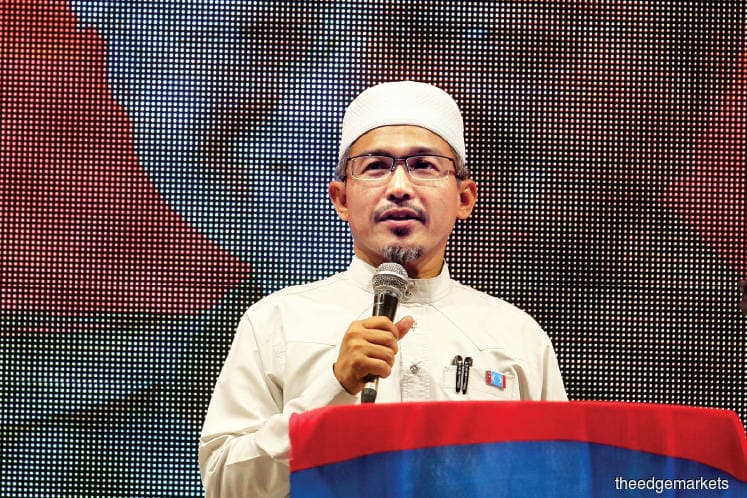

Previously, its election director Dr Dzulkefly Ahmad had emphasised “the need for a leadership that truly understands and grasps the demands of multiculturalism while always remaining principle-centred, just and truthful” in political Islam.

Comfortingly, Pakatan has expertise in religious matters as it counts respected personalities such as Nik Omar — the son of the late PAS spiritual leader Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Mat — as members.

Amanah will also have to consider the views of its partners in Pakatan, particularly DAP, which has been consistently held that Malaysia is a secular nation even though Islam may be the religion of the federation.

Back at the helm after leading Pakatan to victory on promises to reform key institutions, Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad can also be expected to steer the nation towards a more moderate, tolerant Islam in his second time in the driving seat.

Unlike his predecessor Datuk Seri Najib Razak, who willingly cooperated with PAS in the furtherance of its conservative Islamic agenda — he needed allies because of his precarious position stemming from the 1Malaysia Development Bhd scandal — Dr Mahathir will not be so obliging.

Given the Treasury’s mountain of debts left BN, the prime minister might even move to trim the staggering RM1 billion annual budget set aside for the federal department for Islamic development or Jakim.

It should be noted that Jakim was established in 1997 none other than Dr Mahathir. But Jakim has increasingly come under fire for what critics perceive as its promotion of Islamic extremism rather than moderation.

At present, Jakim’s status is still up in the air with the Muslim community split between wanting to keep it and disbanding it.

Admittedly, it will not be easy for Pakatan to recalibrate and improve the efficiency of religious institutions or to reorganise the overlapping common and syariah laws. Even so, the coalition’s diverse presidential council, which includes PKR’s Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim and Amanah’s Mohamad Sabu, is expected to be fair, and provide checks and balances.

But PAS is already testing the waters with Pakatan as it recently urged Pakatan to permit the tabling of Hadi’s bill to amend the Syariah Courts (Criminal Jurisdiction) Act, commonly known as RUU355.

“PAS has a serious view of affairs in the interest of Islam and Muslims that needs to be emphasised the newly appointed government in line with a Malay-Muslim-majority Malaysia,” Hadi said in a May 14 statement.

PAS envisions syariah compliance in governance, which it expects to be understood Muslims who make up the majority of the Malaysian populace. The party proved its seriousness in advocating its brand of Islam splitting from Pakatan Rakyat in 2015, partly because component parties, including DAP, fought its attempts to strengthen the power of the syariah courts over Muslims.

PAS strongman and Kelantan Menteri Besar Datuk Ahmad Yakob observed that Amanah’s compromise in advocating syariah led to its failure to make inroads in the east coast in GE14, such an approach being “less suited to the east coast community”.

In the west coast, the opposite is true for PAS, which contested in over 160 parliamentary seats nationwide but bagged only 18.

Notwithstanding the party’s joy at the “green wave” that swept through Kelantan, Terengganu and Kedah, the Malay-majority states have always been PAS strongholds since its inception.

However, in mixed-majority states, voters embraced Pakatan’s federal ambitions and rejected PAS’ renewed conservative approach.

In Selangor, PAS was reduced to winning just 1 of the 47 state seats contested. Research director Dr Mohd Zuhdi Marzuki also lost badly in the Shah Alam federal seat to Amanah.

A party official told The Edge Malaysia weekly that PAS is undeterred its decreasing political presence nationwide as it is counting on its 18 members of parliament (MPs) to perform.

“PAS MPs can still communicate with the party’s state leadership,” he said, stressing that PAS has always survived, even when it had no parliamentary representative in its 67 years of existence. “It is not about winning elections but about doing what we can within our capacity to uphold Islam.”

To others, the outcome is an unfortunate one for PAS, which, in going back to its roots as a Malay-Muslim party, has sacrificed its national aspirations.

But aspiring parties should take note of the rural-urban migration trend.

According to Dr Ong Kian Ming, who won the Bangi parliamentary seat, Pakatan performed very well in ethnically mixed or heterogeneous federal seats where no one race comprised more than 70% of the electorate.

His analysis of the GE14 results shows that Pakatan won 73 or 88% of the 83 mixed parliamentary seats, while BN snagged the remaining 10. PAS did not win a single ethnically mixed parliamentary seat. “These constituencies have become and will become increasingly important in Malaysia’s electoral landscape with increasing migration to urban areas,” Ong stressed in a statement.

While non-Muslims continued to give overwhelming support to Pakatan, at the heart of its historic win was the huge swing among Muslims who make up at least 53.9% of the electorate. Their increasing acceptance of Pakatan’s moderate approach to Islam may neutralise the old breeding grounds for religious radicalisation.

But whether or not Malaysians like it, religion — particularly Islam — sits alongside ethnicity as major components of Malaysia’s politics.

In the long run, the biggest challenge for Malaysia is to disassociate racial sentiment from religion and also to find a judicious middle ground for all. — The Edge Malaysia