This article first appeared in Enterprise, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on July 10, 2017 - July 16, 2017

In 1997, just before the Asian financial crisis, Hing Yiap Group Bhd founder Howard Khoo saw his marketing building and much of his inventory burn to the ground. While he was helping put out the fire, he spotted a “For Rent” sign at an adjacent factory and sent his secretary to book the space and put down a deposit.

He then rearranged his other offices to make place for the marketing staff. He mobilised his staff and they worked around the clock to replenish his inventory. He also reached out to other factories and suppliers for help.

The company was almost back to normal in two weeks. It was a testament to Khoo’s ability to turn a bad situation around and the market took notice of it. After all, Hing Yiap had just been listed and investors were wondering whether the company would survive and if they would lose the money they had put into the stock.

Khoo’s quick thinking and prompt action sent the right signal to the market. People realised that this was a CEO to be reckoned with. It also restored the confidence of his big distributors — Parkson, Jusco and The Store, to name a few — in the company.

The funny thing is, Khoo had not even thought of becoming an entrepreneur. He was from a small town in Sabah and he studied architecture and town planning in university. In 1985, when the country was going through a major recession, his father-in-law, who ran a successful fabric manufacturing concern, became terminally ill. Although the business was still doing well, his partners started cashing out. Khoo’s father-in-law had been the driving force of the business and without him, they were not confident of continuing it.

Khoo’s wife, who had been an accountant in her father’s company for the past three years, asked him to join the business. He agreed and they decided to run the company as a husband-and-wife team. At the time, he was only working three days a week as an architect.

“It was an easy decision to make. In 1987, the factory was already making RM10 million in revenue and had more than 100 workers. It was pretty sizeable. But I managed to grow it into a RM100 million company in the next few years,” says Khoo.

Not only that. In the following years, he managed to expand downstream and come out with its own products and brands — namely Antioni and Bontton — which captured 15% of the local sports and casual wear market in the 1990s.

In 1997, he was the first member of the Malaysian Knitting Manufacturers Association to list his company on the Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange.

Be humble

Khoo, who travels around Malaysia and the rest of Asean to share the story of his entrepreneurial journey, attributes his success to two things — the ability to remain humble and to think on his feet.

When he took over his father-in-law’s company, the staff started leaving in droves. Most of them were Chinese-educated and were afraid, among other things, that the new English-educated CEO with a master’s degree would look down on them.

“Almost the entire sewing division — 50 to 60 of them — wanted to resign. There were many factories opening in that area, so they had a lot of choice in terms of employment,” says Khoo.

He refused to sit by and watch the company crumble. He called the workers personally and begged them to stay. He shared with them his plans for the company.

He also let them know how much he respected them. “I told them that I definitely did not see them as uneducated. They were educated, just in a different medium. And as far as I was concerned, they were my equals.”

Khoo not only convinced some of the workers to stay, but got them on his side to try and convince those who were wavering. In the end, the company only lost 10 to 12 employees. It had been a trial by fire and he came out of it, with just a few burns.

Automation and expansion

Because Khoo was humble and open, he learnt the ropes very quickly and was one of the first few to adapt to the changing business environment. “I knew nothing about the industry, so I had to learn quickly. I mingled with people from the knitting association and went to a lot of seminars,” he recalls.

Khoo met one of his old professors at a seminar in Penang, who was giving a talk on the importance of automation rather than relying on cheap labour. It was this professor who advised him to expand downstream for higher margins.

As a result, Khoo invested in new machinery after taking a soft loan from a Japanese bank, at an interest rate of 3.5%. “The factory was generating a profit of RM500,000 a year and I decided to invest a few million in machinery to automate our working process. My wife was initially concerned about the size of the investment, but I convinced her by showing her the numbers. She is an accountant, so she understands these things,” he says.

It turned out to be the right decision as his investment paid off. The new machinery increased the factory’s capacity significantly. Also, he had the advantage of being one of the first local players to go down this path.

Shortly after, Khoo followed his professor’s other piece of advice and ventured downstream. It required greater complexity in terms of manufacturing processes, but it would also pay better.

He also created the company’s first brand, Antioni. The sportswear it produced, including football jerseys and track pants, gained huge traction, especially in the Malay market. He decided to sponsor the Malaysian Southeast Asian Games contingent in 1989, just three years after he created the brand.

This gave Antioni tremendous exposure. “The press covered the games two weeks before it started. They wrote about the athletes, how they were preparing for the games and also their sportswear,” says Khoo.

After the games, the brand started making a profit. Then, he got the licence to manufacture and sell the BUM Equipment brand of clothing in Malaysia. The profits rolled in even faster. “It only took us a year to be profitable,” says Khoo.

International brands such as Nike and Adidas were already in the local market, but the products fetched a much higher price and were only affordable to the affluent. Antioni and Bontton, on the other hand, only sold for RM30 to RM40 apiece.

Reacting swiftly

Hing Yiap became more profitable as it expanded downstream. Not only were the margins higher, the company had a much healthier cash flow. “The fabric manufacturing business had four-month credit terms in the old days. That was very long, but it was industry practice,” says Khoo.

Not long into the Asian financial crisis, after the company had recovered from the fire, he found himself confronted by yet another situation. Standard Chartered Bank, on orders from its headquarters in London, had pulled its credit facilities from small and medium enterprises (SMEs) such as Hing Yiap.

Again, Khoo was on the ball. He reached out to local banks such as AmBank and RHB Bank and managed to get even higher credit facilities because of the company’s good track record. He credits then prime minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohammad for this. “He told all the local banks not to retreat as all the industries would fail if they did.”

The company managed to weather the Asian financial crisis without any red ink on its books. But 11 years later, during the global financial crisis, it lost money for the first time in history. The board of directors, who were independent parties, came down very hard on Khoo.

“I had never made a loss. This was the first time and it was due to bad debts as four of our SME distributors were in distress. For the first time, the board shot questions at me that I could not answer. ‘Could I get the money back? Was I sure?’ My ego took a real beating,” he recalls.

Khoo admits that he had stopped taking such an active role in the business at the time. Things were running nicely and he thought he did not need to be personally involved.

When the company got into difficulties, he moved once again to the front line. He started visiting all the distributors, identifying their problems and restrategising the business. He even went to small towns such as Sandakan, Tawau and Batu Pahat to talk to the managers of the shops about how to improve their business and raise morale. With his active and spirited intervention, the businesses were soon back on track again.

Selling his stake

In 2011, Khoo decided to cash out. He felt that he had taken the company as far as it could under his leadership. So, his family sold its 50.02% stake in the company to Everest Hectare Sdn Bhd and it was renamed Asia Brands Bhd.

The retail apparel industry has seen rapid changes with the rise of e-commerce. Foreign brands have entered the local market and physical stores have slowly phased out. These two factors mean that consumers will have more choices and margins could be lower going forward.

“I would say that in the next 20 years, maybe 80% of consumers will buy things online,” says Khoo, adding that for apparel companies to keep growing their profit, they will have to drive their sales up significantly. “If you draw two lines representing the profit and sales volume of an apparel company, the line that stands for volume has to curve steeply upwards for the profit line to grow steadily.”

Having run the company for so long, Khoo was unable to let it go without a pang. He went through a period of soul searching, trying to figure out what his next step should be. “I felt lost. I used to hit the ground running every day. And now, I was not sure what to do.”

It took him about two years to decide that he wanted to be an investor while trying to give something back to society. One way of doing so is to share the knowledge and experience he has gained over the years as an entrepreneur and businessman.

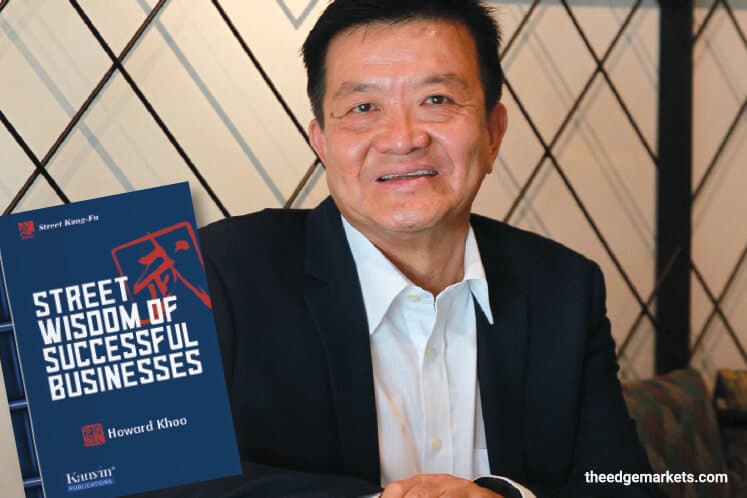

That was why he wrote his first book, Kung-Fu Series: Street Wisdom of Successful Business, which is published by Kanyin Publications Sdn Bhd. Now, he travels around the region giving talks on entrepreneurship. His life has come full circle.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.