This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on May 22, 2017 - May 28, 2017

HI Mom, I know it’s Mother’s Day, but you’ll have to have dinner without me. I won’t be able to get out of the office ... this ransomware attack is really bad.”

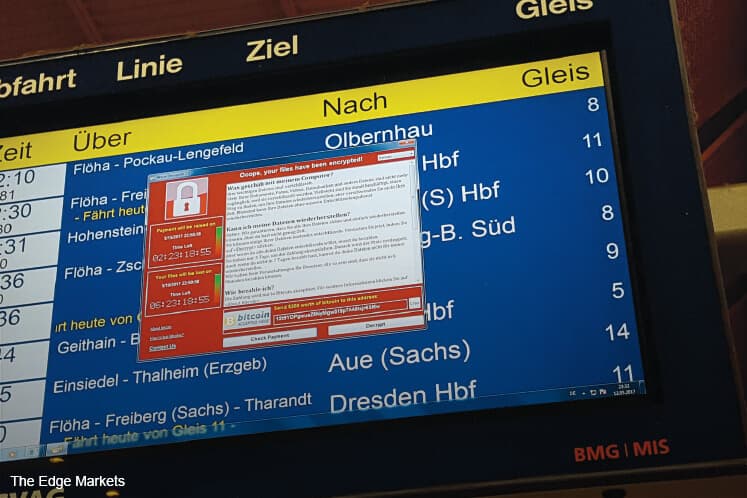

For many mothers with sons or daughters working as IT personnel, they would have likely received phone calls similar to this on Sunday, May 14, about 48 hours after the WannaCry ransomware attack was first reported.

By this time over 200,000 computers had been hit globally, mostly in the western hemisphere. Among the organisations hit were the UK’s National Health System, a French Nissan-Renault car factory and Spain’s Telefonica.

WannaCry took advantage of a Microsoft Windows exploit known as Eternal Blue, once a trade secret of the US National Security Agency. It was such a major exploit that Microsoft even invested resources to roll out patches for operating systems it no longer supported, like Windows XP.

The hackers’ demands were simple: pay them US$300 in bitcoin or lose all your data.

Fortunately for Malaysia’s critical digital infrastructure, it appears that the defences held. To date, there have only been sporadic reports of individual users being affected.

Despite the worst fears of IT personnel, for most companies, it was business as usual when Monday came around.

But that doesn’t mean Malaysian companies should be complacent. The timing of the attack had a big role to play in the severity of the malware attack in the eastern hemisphere. Most employees had already left the office for the weekend, sharply reducing the risk of computers being infected.

“If WannaCry had hit in the middle of the work week, there is no doubt the damage would have been much worse. The weekend also gave IT personnel and security vendors time to react to the malware; for antivirus solutions to be rolled out and vulnerable computers to be patched,” explains Eric Yeow, vice-president of Firmus Sdn Bhd, a regional cybersecurity firm.

Also fortuitous was the accidental discovery of a “killswitch” by a cybersecurity expert over the weekend. This effectively put a halt to the initial wave of attacks.

While variants would soon emerge without the killswitch, a combination of public education and patching would reduce the virility of the so-called WannaCry2.0.

In short, a combination of preparation and luck shielded Malaysia from one of the deadliest cyberattacks of late.

Cases under-reported

Government agencies like CyberSecurity Malaysia and its response arm, MyCERT (the Malaysian Computer Emergency Response Team), have been proactive in public education in an attempt to discourage complacency.

However, there has been a stark lack of cases reported in Malaysia despite the damage WannaCry wrought globally.

In fact, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) announced on May 14 that no cases had been reported as at 10am.

“It is unlikely that none of the major corporates were hit at all. In Malaysia, such attacks tend to be underreported,” says Yeow.

But while large corporates have been spared this time, he points out that small and medium enterprises are especially vulnerable due to a lack of resources.

Fortunately, such cyberattacks also tend to be less disruptive for SME operations. A manufacturer, for example, can still continue its operations even if the computers used for financial purposes are affected.

“This is why you tend not to hear reports,” explains Yeow.

That said, channel checks within the industry reveal that some of the earliest known victims of WannaCry appear to be a handful of hotel operators in Kuala Lumpur. Fortunately, operations have only been minimally disrupted thus far.

But even as this story is being written, reports have emerged of another type of malware that has been utilising the same exploit — Adylkuzz.

Unlike WannaCry however, Adylkuzz is not ransomware. Instead, it operates hidden in the background, using the infected machine’s resources to mine for Monero, a type of cryptocurrency not unlike bitcoin.

“One difference between Adylkuzz and WannaCry is that it is advantageous for Adylkuzz to remain undetected and run as long as possible to maximise the amount of time a machine can be used for mining. This creates an incentive for the cybercriminals of Adylkuzz to cause minimal damage and stay under the radar whereas WannaCry loudly informs the user that a compromise has occurred and causes massive destruction to the data on a platform,” McAfee chief technology officer Steve Grobman wrote in a statement last week.

“Organisations should never conclude that the absence of a major cyberattack means that they have effective cyber defences,” he added.

Structural vulnerabilities persist

Amid the fear spread by WannaCry, it is important to be aware that such ransomware attacks are far from new.

Horror stories are rampant in the cybersecurity industry, like the one about a company’s human resources administrator who lost his company’s entire payroll data to a ransomware attack.

But past attacks have also driven corporates and regulators to ensure that adequate defences are erected. And in the event the defences fail, contingency measures like data backups have been put in place.

Nonetheless, experts like Yeow concede that it is impossible to completely ward off attacks. In fact, a new school of thought plans an organisation’s cybersecurity on the premise that it has already been compromised. After all, the biggest point of vulnerability in any system is the user.

“Most ransomware can’t get into your system unless you let it in by clicking on a link or downloading a document. In other words, you have to infect yourself,” he explains.

The best defence against such hacking attacks is to patch regularly. But that isn’t always so easy.

“Did you know the patch to address the vulnerability exploited by WannaCry was available in March? That’s right — Microsoft released the patch two months ago to protect from this vulnerability when it was discovered by Shadow Brokers (a group of hackers),” says Yeow.

The trouble, however, is that many large corporates have patching cycles that can take more than a month to implement, leaving them vulnerable.

A new patch needs to be tested to see if it is compatible with other software running on the system. This testing and implementation takes time, perhaps one month if the company is very efficient.

But as companies are working on patching their systems, hackers are also working on reverse engineering every new patch that is released. The aim is to identify the very security flaw the patch was meant to cover, and develop new malware that exploits it.

“WannaCry and Adylkuzz show how important security patches are in building and maintaining those effective defences, and why regular patching plans to mitigate environment vulnerabilities need to become a higher priority,” explains Grobman.

“Whenever there is a patch that must be applied, there is a risk associated with both applying and not applying it. IT managers need to understand what those levels of risk are, and then make a decision that minimises the risk to their organisation. Companies that have become lax in applying patches may not have experienced any attacks that can take advantage of those vulnerabilities, reinforcing the behaviour that it’s okay to delay patching,” he cautions.

Furthermore, it is important to be aware of the fact that cybercrime is a huge and profitable industry. It typically involves large syndicates with ample resources at their disposal, Yeow points out. “Zero-day security vulnerabilities are traded on the black market for large sums. Many organisations can use it for their personal agenda.”

In contrast, cybersecurity efforts are constantly playing catch-up.

Traditional anti-virus solutions are overwhelmingly focused on blacklisting — cataloguing known threats and protecting systems from it. However, this is little defence against new and unidentified threats, or existing threats that have been modified.

Until more advanced anti-virus solutions are developed to detect and counter previously unknown threats, the cat-and-mouse game of digital security will continue.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.