This article first appeared in Personal Wealth, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on May 8, 2017 - May 14, 2017

Fine wine, one of the most popular passion investments, has delivered returns of more than 200% in the last decade. Experts discuss its history, investment risks, performance outlook and how the asset class can enhance your portfolio.

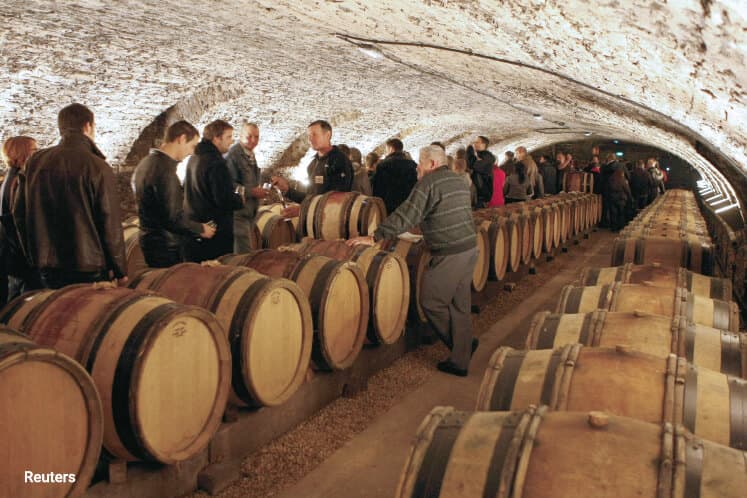

Fine wine has become one of the most popular passion investments since auction houses in England commenced sales in the mid-20th century.

Last year was a stellar one for this alternative investment. Fine wine’s performance outshone that of all other luxury goods, including classic cars, the traditional top performer and its closest competitor.

According to the Knight Frank Fine Wine Icons Index, the asset class recorded 24% growth last year. This was significantly higher than the 9% increase of the HAGI Top Index, which tracks the performance of rare classic cars.

The outperformance was mainly driven by the resurgence of Bordeaux wines, says Aarash Ghatineh, global sales director at UK-based Cult Wines Ltd. “If we look at the import figures across China, of the US$2.4 billion worth of wine imported last year, about 60% were Bordeaux wines.”

According to Knight Frank’s Wealth Report 2017, Bordeaux wines saw annualised growth of more than 30% last year. The region’s wine economy, meanwhile, stood at €1.4 billion (RM6.6 billion).

Although Bordeaux wines suffered a steep decline in 2011, they are back in favour due to Brexit and its repercussions, says Philip Staveley, head of research at UK-based Amphora Portfolio Management.

“Fine wine is a pound sterling-denominated investment. When the Brexit vote took place last June and the pound declined, the fine wine market did very well. Foreign investors found that investments were about 15% cheaper,” he says.

“The UK is going to have a general election, so the pound is very firm and the consideration is that the country will grow stronger after the election. Thus, non-UK investors can benefit from the knowledge that the pound will continue to rise and be able to hedge in their own currency in those terms.

“Additionally, if they are concerned about how little money they are making from equities, bonds and fixed deposits, or worried about geopolitical risks, alternative investments such as fine wine are a very good way to enhance their portfolio.”

Amphora is a fine wine advisory firm that helps investors build, store and manage their fine wine portfolios.

Increasing participation and demand imbalance

Fine wines are those that improve over time as they age in the bottle. All of these wines are considered investment-grade. Non-investment-grade wines have a shelf life of about seven years before rapidly deteriorating, but fine wines can last more than 50 years and continue to see higher values.

As wine is consumed, the supply effectively decreases. This imbalance between demand and supply is the main driver of investments.

“For other luxury goods such as gold, supply can be increased by producing more to meet the rising demand. But you cannot reproduce certain aged wine,” says Staveley.

“The production of fine wines is limited by a statute in the Bordeaux Wine Official Classification of 1855, which says only a certain amount can be produced each year. Over time, their rarity increases, causing prices to eventually rally, like the fine art market.

“For example, if you happen to own a case of 1961 La tour, you may be the last person on earth owning it because the rest have been consumed. If that is the case, you can basically set your own price.”

Before fine wine was considered an alternative investment half a century ago, only a few affluent buyers would buy more wine than they intended to drink so that they could sell it at a later date to fund subsequent purchases. Today, the wine market is more diverse and improvements in wine-making technology, easily accessible data and greater appreciation and understanding of the process have made it easier for investors to jump on board.

As a result, the fine wine market has seen a significant increase in participation, says Staveley. “Ultra-high-net-worth individuals (UHNWI) aspire to the ownership of luxury goods, be it Rolex watches, Range Rovers, diamonds or … whatever. Fine wine sits together with these goods. Most of them generally develop a passion for fine wine and continue adding to their collection.”

The demand for fine wine is growing in Brazil, Russia and India. “There is a cultural evolution happening in India. The older generation are only familiar with beer and whisky, but the younger generation are becoming very knowledgeable about wine. Wine consumption among those below 40 years old is rising dramatically. The problem is, the import duty on fine wine is 160%,” says Staveley.

“Now, even if they are wealthy, they would not want to give 160% to the government. So, when they travel to the UK, Hong Kong or Singapore, they get a couple of bottles of fine wine to take home.

“The interest in fine wine has grown so significantly in India that one of our partners there actually owns a vineyard just outside of Mumbai. It had 250,000 visitors last year. It is the largest local producer in the country. The wines are called Sula Wines.”

There are various ways to invest in fine wine. Besides owning physical assets, one can also invest in a winery, wine stocks and wine funds. However, when it comes to portfolio management, Ghatineh advises investors to stick to physical assets.

“Investing in wine funds, for example, does not give you much control over what goes into your portfolio. You are restricted to the allocations of the fund and most wine funds in the market are almost 95% exposed to Bordeaux. You don’t get as much exposures to other regions such as Burgundy. If you track the wines in the Burgundy 150 Index for the past 15 years, you can see returns of more than 250%.

“Although Bordeaux can produce excellent returns, it can also go through periods of correction. The most recent downturn was from 2011 to 2014, where some of Bordeaux’s top labels (first growths) lost around 40% of their value. At the time, our portfolios were long in other regions such as Burgundy and Champagne. I suppose this reinforces the benefits of investing in physical assets rather than a fund structure.”

Even then, investing in fine wine is risky. For one, the market is unregulated. Many have cried foul after being deceived into buying wines that have little to no resale value. Prices can fluctuate and it is generally a long-term investment, typically 5 to 10 years. Shorter-term investments, while they can give good returns, are not recommended.

“Those who have expertise in the market may suggest that you keep your investments for more than five years. Sure, if you buy the right wines at the right time and the right price, you would be able to make money. But this is not as dynamic a market in terms of volume turnover and price movements as some of the other mainstream markets. Thus, it is important for investors to understand that this is not a trading environment where you can just go in and come out,” says Staveley.

He adds that those who keep their investments for a long period, especially the highly sought-after bottles, stand a chance of reaping a great yield. For example, there are only 450 cases of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, a Burgundy wine, produced each year for global distribution. “It is almost immediately scarce, thus causing supply and demand imbalance straight away.”

The wine industry is also heavily influenced by critics, says Staveley. “Robert Parker, the most prominent critic, has always graded wines. The wines that receive 100 points from him are perceived as perfect, highly sought-after wines.

“Today, Parker is a bit older. He has stopped tasting Bordeaux wines and now restricts himself to California wines. What this means is that his 100-point wines are growing in demand because soon, there will not be any more of them. And as he is a critic with a dominant influence on the market, our calculations suggest that his judgement is worth fully four times that of all the other critics put together.”

Diversifying your portfolio

Investment-grade wines are those that are age-worthy and increases in value and demand over time as the supply dwindles. Although most of the investment-grade wines are red, some of the white wines and champagnes are also structured for long-term ageing.

French wines, namely Bordeaux and Burgundy, are the most in demand investment-grade wines. According to Berry Bros & Rudd, a case of 12 bottles of Lafite Rothschild 2004 is valued at £6,200 (RM34,688).

Investors are able to build their physical collection by buying directly from wineries and merchants or through auction houses. They may also get investment firms and advisers to help build their portfolio and navigate the investments.

Investors should not put all their eggs in one basket, says Ghatineh. Like other asset classes, wine investments should be spread across sectors and regions.

“It is critical for investors to have a balanced portfolio of different regions, vintages and strategies. What we recommend now is 60% exposure to Bordeaux , 20% to Burgundy and then 5% to Champagne, RhÔne, Italy and the US,” he says.

This is also the case when investors come in with only a small amount of investment. While some investors spend £5,000 to buy a case in the hope of reducing their risk exposure, it is not a very efficient strategy, says Staveley. “When diversified correctly, fine wine can give you significant returns. If you invest £10,000, then you can have four or five types of wine. But you are not getting any exposure to first growths as it costs about £5,000 per case.”

Staveley recommends that beginners invest £20,000 to get exposure to all parts of the world. “When you get more comfortable, you can build your portfolio until it reaches £100,000. At this point, you can even get exposure to cult wines such as the California Screaming Eagle. While some people like a bit of exoticism in their portfolio, due to the risk element, I would not recommend allocating more than 10% of your portfolio to these trophy wines,” he says.

Due to the vast amount of information online and offline about investment-grade wine, a lot of investors buy and manage their own supply. They go to merchants such as Berry Bros & Rudd, one of the world’s largest wine merchants, and keep their wines at a bonded warehouse or in their cellar at home.

“The problem with this is that the business model of these merchants is to buy as cheap as they can and sell for as expensive as they can. They do not have your best interests at heart,” says Staveley.

“They make money from the size of the spread, so their bid-offer spread for fine wine can be as wide as 30%. If you are buying through Berry Bros & Rudd for £10,000, you may only get £7,000 if you try to sell it the next day — far less than their offer price.

“To get optimum returns, investors can turn to firms such as ours. We are like a private stock broker, where we advise investors on which wines to buy, arrange for storage with a third party and constantly analyse with our algorithm what would be the best action for our clients … all this while they are still fully in charge.”

Working with the right adviser and experts will also allow investors to pick up on upcoming trends or even beat those trends. “It can be tricky going in blind as a collector and investor, especially if you want to invest in something like En Primeur (wine futures, where the wine bottles are purchased before they are released in the market). Therefore, you should work with those who have a track record for growth and experience in the market. We have an intimate understanding of which wines are in demand, where and at what time. Over the last 10 years, our wine stock picking has been unrivalled, culminating in a significant upside for our client portfolios. Cult Wines Portfolio Index was up more than 25% last year, ” says Ghatineh.

Cult Wines currently has 20 Malaysian investors in its database, with an average portfolio of £50,000. Meanwhile, Amphora is trying to develop investor interest in the country, according to Staveley.

“We went to Kuala Lumpur once not too long ago on an exploratory trip and met a few Malaysian

HNWIs. But they were very familiar with the market. In fact, one of our Malaysian friends owns a vineyard in Bordeaux and produces two wines. We will probably visit Malaysia again soon,” he says.

Professional wine traders may sell their collections at any of the three wine exchanges in the UK — Berry Bros & Rudd, Liv-ex and Cavex — even though they mainly focus on top Bordeaux wines. Individual investors typically turn to merchants, traders and auction houses to sell their collections, especially with the rise of user-friendly fine wine auction portals such as WineBid, Christie’s and K&L Wine Merchants.

Historical performance

Over the past decade, fine wine investments have increased 267% on the Knight Frank Luxury Investment Index. Only classic cars have performed better, rising more than 450% during the period.

However, fine wine is considered a more attractive investment due to its easy access, market size and liquidity, says Aarash Ghatineh, global sales director at UK-based Cult Wines Ltd.

“Fine wine has a much lower barrier to entry than classic cars. For example, if you want to see returns in classic cars, you must shell out a significant amount of money to buy a Ferrari Dino, whereas you can buy a case of investible wine for less than £2,500,” he says.

“On top of that, in the classic car secondary market, you may have to list your car for 18 months before you can sell it. But the global wine market has US$10 billion worth of wine traded annually.”

Ghatineh says all the fine wine indices were up about 20% last year, while the Liv-ex 50 was up 26% — its strongest performance in the past five years. However, its performance has not always been this good.

Although fine wines have produced almost 15% per annum in compound returns over the last 30 years (excluding nominal storage fees), their performance in the past 10 years has been a schizophrenic ride, says Philip Staveley, head of research at Amphora Portfolio Management.

“Up until the 1980s, fine wine was a tightly held closed market. It went up very gradually in a straight line in accordance with post-war global economic growth and rising inflation, and was enjoyed by relatively few people. In the 1990s, however, more Japanese began buying fine wine and the market had a boost. Eventually, it opened up,” he says.

Liv-ex 50 is the industry’s benchmark. It tracks the daily price movements of the most traded wines in the market. It tracks the 10 most recent vintages of first growths such as Haut Brion, Lafite Rothschild, Latour, Margaux and Mouton Rothschild. First growths refer to the top Bordeaux wines.

Around 2005, the global fine wine market experienced a significant impact due to the involvement of Chinese investors, especially after the Hong Kong government abolished import duties for wine and beer in 2008. This led to a frenzy of activity among retailers and importers and eventually caused prices to skyrocket until 2011.

“The market at this point focused mainly on Bordeaux. The Chinese interest was even more narrowly focused on the left bank of Bordeaux (first growths). Afterwards, the interest spread to second and third growths too, with names such as Durfort-Vivens and Cos d’Estournel,” says Staveley.

“However, in mid-2011, several factors torpedoed the market. This includes concerns over the euro, change of administration in China and worries about China’s economic growth. The market became a playground for speculators.”

Eventually, the buyers disappeared and the speculators were left holding on to stocks that were dumped into the market, causing the Bordeaux-centric indices such as the Liv-ex 50 and Liv-ex 100 to narrow. As investor interest left Bordeaux, it spread to other parts of the globe, such as Napa Valley in the US and Tuscany in Italy.

“The Bordeaux-centric indices consolidated over the next few years until mid-2015, when it started to rally again. The real consequence of the correction was that the market became much broader, so the broader indices such as the Liv-ex 1000 only corrected a little. That was the performance of the fine wine market until it rallied last year,” says Staveley.

Storing your wine

Storage is critical when it comes to fine wines. Even the best investment-grade wines lose their value when they oxidise or their flavours dissipate. To properly store wine, investors need to have a dark area with optimal temperature (about 12oC) and humidity levels, which can be accomplished in a cellar in certain countries. Alternatively, they can use chillers and humidifiers. But they can be very costly to purchase and maintain over a long period of time.

To protect their extensive wine collection from damage, fire, theft, oxidation, temperature and variability, investors may also purchase wine insurance from providers such as AIG Private Client Group and Insure Your Wine. These policies offer international coverage, which means that each item included in the policy is protected regardless of its location.

If investors choose not to store their collections at home, they can look for service providers that offer proper storage facilities for fine wines such as the Singapore Wine Vault, which is currently the largest in Southeast Asia. There are also options outside the region. Most investors who build their wine collections via portfolio managers or firms will find their wines stored in bonded warehouses such as the London City Bond.

As the cases of wine may be valued at a high price over time, investors are advised to create a paper trail of provenance as proof of their authenticity. Sometimes, investors with good experience, connections and influence in wine investments may have the opportunity to buy cases from popular wineries at low prices.

Beware of scams

Wine investments can be risky as the market is unregulated. Over the past 30 years, the market has been tainted by scams carried out by so-called “wine experts” who target unsuspecting or ignorant buyers.

To avoid buying wines that have little to no resale value, investors must carry out their due diligence and determine the value of the goods before any transactions are made, says Aarash Ghatineh, global sales director at Cult Wines Ltd.

“Unfortunately, there have been a lot of unscrupulous companies that have either misled investors, given unrealistic expectations or overpriced wines. Therefore, for novice investors, due diligence is absolutely critical,” he says.

“First and foremost, investors must look at the various online sources for prices of the fine wines they intend to buy. If someone recommends you any type of wine at all, you can go to platforms such as Liv-ex to check the price. There are also search engines, such as Wine Searcher, that give accurate prices of wines and spirits.”

Philip Staveley, head of research at UK-based Amphora Portfolio Management, says investors should be aware that not all expensive wines have resale value. “Australian wine, for example, improves over time. But there is no secondary market — you cannot sell them.

“Unfortunately, there are firms that sell these bottles and claim that they are valuable and are worth keeping for a long period of time. We often get people who ask us to sell their £50,000 Australian wines, but the most they can get is 20 or 30 pence per pound sterling if they are lucky.”

Those who run wine investment scams tend to pose as credible firms, with fancy office space and staff dressed in suits. However, these firms often lack transparency, company history and track record. That is why it is important to always ask for proof of authenticity before making any investments, says Ghatineh.

“For instance, companies such as ourselves have long been established in the fine wine industry. We have managed to simplify the market for our clients and present our information in a unique form — whether you speak the language of wine or investments, our product caters for both audiences. Our clients also have the ability to track their portfolios through an online client portfolio, where values are taken directly from the Liv-ex on a daily basis.”

Investors should also make sure that they are, in fact, owning the physical assets. Staveley says often times, investors are fooled by the high pressure sales tactics of those running the scam and have no idea where their collections are stored.

“You have to see what you have bought to know that you are taking full charge of your investments. For example, our wines are stored in a bonded warehouse in the UK by Vine, which is owned by the Liv-ex system,” he says.

“When our Asian investors are in the country, we bring them to see their wines at the warehouse in Tilbury Docks. It is not a very romantic trip, but it is very important for them to do so to confirm that the wines they own are safely stored and, most importantly, are real.”

The Bordeaux classification

The Bordeaux Wine Official Classification of 1855 is a ranking of the best wines in the region. Here is a selection of red wines according to their classification.

First Growths wines (also known as Premier Crus)

Wines that have achieved this status are Lafite Rothschild, Latour, Margaux, Haut Brion and Mouton Rothschild.

Second Growths wines (also known as Deuxiemes Crus)

Wines that have achieved this status include Leoville Barton, Durfort-Vivens, Gruaud Laroze, Lascombes and Montrose.

Third Growths wines (also known as TroisiÈmes Crus)

Wines that have achieved this status include Langoa Barton, Giscours, Malescot St Exupery, Ferriere and Marquis d’Alesme.

Fourth Growths wines (also known as Quatriemes Crus)

Wines that have achieved this status include Saint-Pierre, Duhart Milon, Branaire Ducru, Beychevelle and Prieure Lichine.

Fifth Growths wines (also known as Cinquiemes Crus)

Wines that have achieved this status include d’Armailhac, Du Tertre, Haut Bages Liberal, Pedesclaux and Belgrave.

A Malaysian perspective

For someone who loves drinking wine as much as Jim (not his real name), it was only natural to collect and subsequently invest in cases of investment-grade wines. He started his collection in the 1990s, when the asset class was not as popular in the country compared with Europe or the US. “The investment started with a natural liking for the beverage. Since it is an expensive hobby, people who did it, did it out of passion,” says Jim.

Based on his observation, people in Southeast Asia tend to invest in fine wines due to the influence of western culture. After living in Europe or the US for a few years, it is a norm for affluent individuals to collect fine wines, he says.

Jim buys his collection from merchants such as Berry Bros & Rudd, Farr Vintners, Yapp, Fine+Rare and even Singapore-based Grandvin and Vinum. Most of his collection is stored in a bonded warehouse in London, which he visits from time to time.

He says regular collectors would have about 100 cases (12 bottles per case) of fine wine while serious collectors would have more than 300.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.